Recently a British classics professor named Mary Beard was inundated with nasty comments after she participated in an online forum at the Guardian. “In one of the milder examples, Beard was called ‘a vile, spiteful excuse for a woman, who eats too much cabbage and has cheese straws for teeth,’” the Guardian reported. “Beard’s features were even superimposed on an image of female genitalia.”

Her story is remarkable precisely because it is so relatable. Buzzfeed’s Ben Smith was dismissive, tweeting, “Am I wrong in thinking it’s crazy that people still read, much less write about, blog comments?” But many people do, especially writers who are up-and-coming and those who aren’t used to being in the public eye. (Beard appeared on a BBC1 TV show; a blog posted the clip.) Journalists and the experts they quote aren’t the only ones dealing with this type of hate. As Matt K. Lewis writes, “past generations could mostly leave their problems at work. Their bullies and bosses didn’t follow them home — didn’t hound them on their iPhones.”

For women, the effect is often compounded. “A woman’s opinion is the mini-skirt of the internet,” writes British columnist Laurie Penny. “Having one and flaunting it is somehow asking an amorphous mass of almost-entirely male keyboard-bashers to tell you how they’d like to rape, kill and urinate on you.” Most women have met with personal attacks not just in the comments, but on Facebook and Twitter and in their e-mail in-boxes. I have a Gmail tag for the hate mail I get, and it contains such gems as this response to an article I wrote about contraception coverage in the health reform bill: “Keep your damn clothes on and your tits and vag covered your BF (future BF, husband, etc.) doesn’t want your privates public.” Okay, then! No more going out in those crotchless jeans. (Sorry to make you roll solo on this one, Brooke Hogan.)

I’ll let you in on a secret, though: I love my haters. I relish my hate mail because it’s how I know an article I’ve written is really making the rounds. But for most women, ad-hominem attacks — many of them violent and sexual in nature — have a chilling effect on their willingness to speak up publicly as experts. Fellows in the yearlong Op-Ed Project program, which is designed to empower women to become opinion leaders, learn not just how to write op-eds and speak in soundbites but also how to handle the negative feedback and “address opposition” when they become spokespeople in national media. “I have a mantra: If you say things of consequence, there may be consequences. But the alternative is to be inconsequential,” the Op-Ed Project’s founder and CEO Katie Orenstein told me. “My point is not that we should speak up at any cost, but rather that we can’t allow fear of negative feedback to determine what kind of voice we have in the world.”

“Don’t feed the trolls” is advice that bloggers of all genders have taken to heart. But in these days of democratized communication, when even the casual Facebook update can prompt a heated discussion, haters are everywhere. Impossible to ignore. Rather than starving them, savvy people now brag about their trolls, and even use the haterade to their advantage. While the term “hater” has been around as long as hip-hop, it’s become so commonplace for rappers to decry their haters (or thank them, if you’re Kanye) that last year Complex named it one of the biggest clichés in the genre. Haters have also morphed into a meme of their own. You’ve seen the reality TV clips and the GIFs: Haters gonna hate. Hi, haters! Haters to the left. Keep hatin’. The lesson? Haters aren’t something to be feared. They’re validation that you’re a big deal. And they’re fuel to do better. Now you’re inspired to prove that their jealousy is warranted.

“Yes, the more successful you are — or the stronger, the more opinionated — the less you will be generally liked,” wrote Jessica Valenti in a great piece on women and likeability published by The Nation a few months ago. “All of a sudden people will think you’re too ‘braggy,’ too loud, too something. But the trade off is undoubtedly worth it. Power and authenticity are worth it.” Lots of successful people have made it to the top by holding on to their grievances. “A fascinating example to me was Michael Jordan’s Hall of Fame induction speech,” Ill-Doctrine blogger Jay Smooth told me, “which was basically an hour of him listing every time he’d ever felt slighted or wronged going back to high school, until it was clear the secret to his success was how he held on to every grudge he’d ever had like it happened yesterday.”

So what if, instead of averting their eyes and burying their heads in the sand, women who are shouted down online and at work could flip the hate into fuel for success? Last year, after Ellen DeGeneres became a spokesperson for J.C. Penney, a conservative women’s group launched a campaign to get the department store to drop her. “Normally I try not to pay attention to my haters,” Ellen said on her show, “but this time I’d like to talk about it because my haters are my motivators.” Unfortunately, she stopped short of explaining how. This is where a lot of women — those of us who don’t have national talk shows and millions of fans — get stuck.

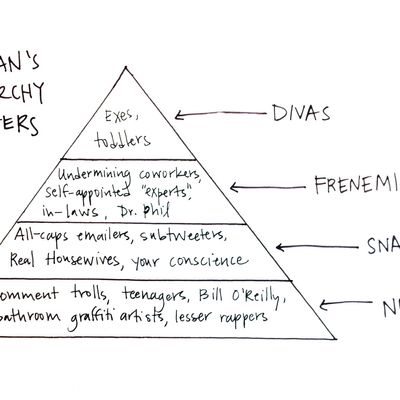

A younger woman who works in media recently wrote to me, “How did you build up a thick skin? Something I’ve always struggled with is not taking things personally and getting upset when people say things that hurt me — in comments, on Twitter, etc.” I explained to her that I have a hierarchy of haters. High-order haters are those who really know how to hurt you; they may have real power or influence in your social or professional world. These are the folks you might consider responding to, or otherwise defending yourself against. Low-level haters are usually people of little professional or social consequence to you. These are the folks who call you fat and ugly because they disagree with your views on, say, the federal debt. The lower a hater is on the pyramid, the more likely it is that the best response is to ignore him — while taking pride in the knowledge that, wherever the hater falls in this hierarchy, his or her very existence means you’re succeeding in having an impact. If you’ve got confidence in your skills — plus a support system of friends and colleagues who are there to back you up — haters can be marginalized.

That doesn’t mean I consider all of my critics to be haters. If I get negative feedback from people who are close to me, strangers who actually care about my work, or experts in the field, I listen. Those people push me to work harder, too. But nothing motivates me like haters. The hierarchy just helps me to compartmentalize them. It’s not that I stop caring altogether, it’s that I care much less about the least consequential among them. And I try to take an Ellen DeGeneres approach with everyone else.