September 5 begins Mercedes-Benz’s biannual fashion week and, right now, models from all over the world are lining up to fill the New York runways. In the past, many of them would be teenagers. Not yet able to drink, not yet able to vote, some of them not yet able to even drive. But this season is different: In June, the New York State Senate unanimously passed a bill advocated by Sara Ziff’s Models’ Alliance that will finally provide labor protections to child models. Though the legislation hasn’t yet been signed into law by Governor Andrew Cuomo, the big agencies still aren’t sending the youngest girls to castings this month. Effectively, this closes a loophole exempting models from child-labor regulations — twelve-hour workdays, required chaperones, mandatory tutoring, and more — that are in place for kid actors, dancers, and musicians.

I was a teen model. This statement does not immediately inspire compassion; it is a thought that one attaches to lucky breaks and glamorous lifestyles. In part, that’s what it’s like. But what I mainly got from the experience was something that took me twenty years to figure out: The symptoms I had developed after my years as a teen model — the hyperawareness, the hair-trigger panic, the dissociation that I called putting on my model-suit — were actually post-traumatic stress disorder.

In January 2010, I moved back to New York to finish college in my mid-thirties, a thing I had been too busy to do as a kid. It was a hard winter. The panic attacks came more frequently. I began taking anti-anxiety medication, along with migraine medication every day, but sometimes this was not enough. Everything was a possible trigger. A classmate laughing when I read a section from an essay about men touching me on a Tokyo train. A writer being openly aggressive at an after-class bar session. Another person standing too close to me, staring at me, talking about me. At first, I didn’t understand what was happening. Why was I so scared all the time? Then my roommate, a psych major who also had PTSD herself from childhood abuse, handed me a chapter in her textbook.

Soon after, I was diagnosed with complex PTSD. Everything led back to my time as a teen model. No one ever connects being a too-young fashion model with trauma, and even if they do, the sympathy is slight. It is associated with veterans of war: soldiers who are sent to the worst of places, who experience the hardest of horrors.

At 15, I was given the opportunity to leave my small southern town and travel as a professional model. The offer was to spend two months of my summer break modeling in Japan. The agency promised my parents chaperones and supervision. When I arrived, I was shown to a compact one-bedroom apartment to share with another teenage girl. They did not show me the grocery store or the nearest laundromat, the bank or police station. They did not show me how to dial an international line home. When I did not book something in the first week, the agency van stopped picking me up in the mornings. Instead, they handed me a complicated map of the Tokyo subway system, calling each night with my appointments for the next day. In the middle of Tokyo Station, I stood frozen. I was 15 and did not know how to read the beautiful characters of the Japanese language. I stood there for ten minutes, reaching out to feel the letters I knew signaled a destination, hoping that somehow the words would become clear.

When I moved to New York, at 16, the same practices were in effect. My agency would lightly acclimate me to the new terrain, then release me to my own devices. It was 1994 — though it’s shocking how little about the industry has changed — a time before e-mail or smart phones. I was placed in a models’ apartment in Tribeca — a slap-dash two-bedroom with pre-fab walls created to house six underage girls. Photographic lighting equipment provided our limited illumination. We wore belly-brushing T-shirts that said “Models Suck.” Bob De Niro was our neighbor. The Bowery Bar gave us free drinks all night.

Our castings could be anything from one of us alone in a reconditioned loft to 100-person cattle-call mania: Heaps of teenage girls on the floor of some midtown high-rise for hours, listening to Walkmans, checking their makeup, chatting, bickering, making plans for the night’s newest club opening. The only adults present would be those that worked on the other side of the camera — the photographers, makeup and hair people, magazine representatives. No moms, no agents. I walked about five miles a day on average over the streets of New York, to and from castings. I’d wear a long-sleeved white shirt to cover the clingy dresses or jeans I was required to wear for auditions — the catcalls were overwhelming. In my backpack, I carried a pair of heels to change into before each appointment, a laminated map with tabs indicating castings all over the city, many in the same one- to two-hour time block, and Ziplocs of Cheerios and little red boxes of raisins — snacks for kids.

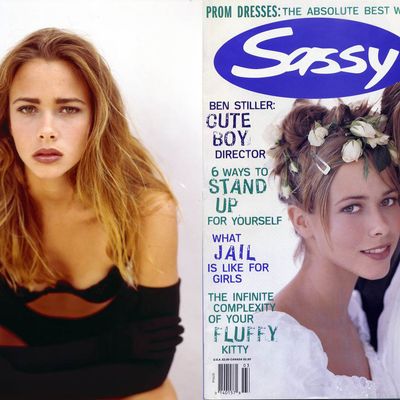

I quit modeling the month I got my first national magazine cover, for Sassy. It was the prom issue. In a large white studio space, we were placed in front of lights so bright that you could feel the heat yards away. They dressed me in pinks and tulle; finger-curled my hair and pinned baby’s breath in a crown. The male model wore a blue suit. We pretended to be sweethearts. We cuddled. We laughed. We were instructed to kiss. We pretended to act like a real teenage couple in love, on their big night — kids going to prom. He had smoker’s breath and smelled like the night before. As I waited for the messenger to deliver a copy, I remember looking out at the balcony of my agency-operated apartment. I remember looking at the mattress I had put outside, hoping the February chill would kill the bedbugs. When the magazine arrived, the pinnacle of my modeling career, the girl in the photo seemed sad.

Countless questionable things happened to me during my time as a model. From neglect to molestation to topless photo shoots to men exposing themselves to being made to stand in a freezing pool until I turned blue, I would be abused for the entirety of my career. Eventually, the highs of the photo shoots began to dull. I started to show signs that things weren’t right; feeling disconnected, hollow, having nightmares. My naturally outgoing personality changed: I became withdrawn and startled easily. It became hard for me to travel new routes, to eat at new restaurants, or even shop at the corner store. I became so timid I no longer spoke. I eventually did not leave my room unless I had a job or a casting.

I quit modeling at age 17. I went on to become an actress, appearing in Buffy and Xena, and starring in my own series, Cleopatra 2525. I was in films opposite Peter Falk and Bradley Cooper. I was on the cover of Maxim. But even today, at age 36, I still have symptoms of the PTSD that was brought on during my time as a teenage model. People with PTSD become preoccupied with anticipating and dealing with threats. They live in a hypervigilant state. Adrenaline hijacks their body chemistry and all they know is fear. I have learned to control the rise when it happens, to try to stop myself from falling back into the dark pool and shutting down. I am currently in treatment, doing EMDR, which helps.

It has been twenty years since I have been a model. While my mattress comes with multiple warning labels threatening legal action if removed, fashion has remained free of necessary regulations — until now.