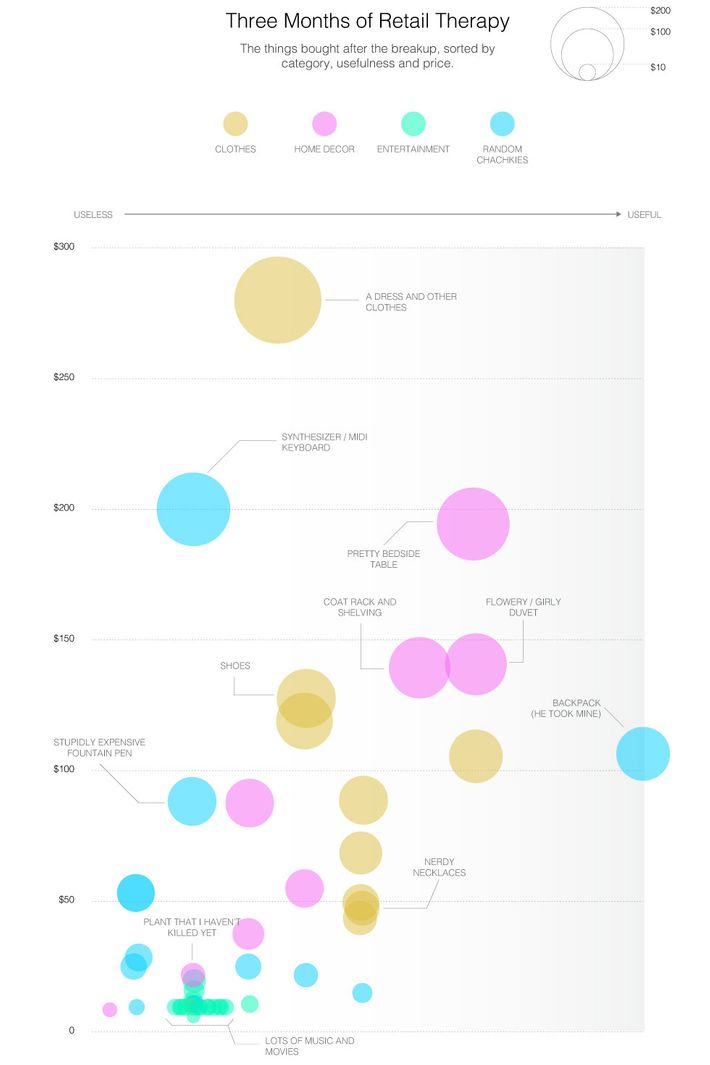

When her marriage fell apart at the end of the summer, Lam Thuy Vo poured her feelings into creative pursuits. She set a Rilke poem to music and sang it in a video. She started a journal, alternating between heartbroken doodles and notes from meeting with her attorney. “It’s the most depressing thing,” the 28-year-old recalls. “He’ll be served ten pages, it will be three to six months, it will cost $2,000. Seeing it quantified like that just haunted me.” An infographic designer by trade, she began drawing charts for things like “Love Received vs. Love Perceived.” A pastel bubble chart titled “Retail Therapy” gives a partial inventory of the data-memoirist’s apartment and displays impulse buys on a scale of “Useless” to “Useful.”

“I was doing an article at the time about the spy gear private detectives use,” Vo continues. “And I thought, why not collect all that data, and supply it to myself?” The result was Quantified Breakup, a blog where she charts her post-breakup sleeping patterns and iPhone-tracked wandering. It’s the right-brain version of her lovelorn Rilke song. Whereas the Quantified Self movement incorporates technology to collect data for self-improvement — like wearing a FitBit Tracker to optimize caloric expenditure — Vo incorporated technology for self-expression. Call it the Quantified Selfie: public, personal data analysis that is more artistic than it is practical. It functions as self-portraiture, emotional self-discovery, or (perhaps) self-help.

Data surrounding issues of the heart can, of course, be analyzed for practical purposes, too. Facebook researchers have experimented with algorithms for predicting breakups, and mood-tracking apps are a recurring feature for both Quantified Self and psychiatric circles. Men who chart their sex lives with spreadsheets have an outcome-focused approach to sex; sharing the spreadsheet is interpreted as bragging. Dieters who track their progress on social media may provide an inadvertent record of fluctuations in self-esteem.

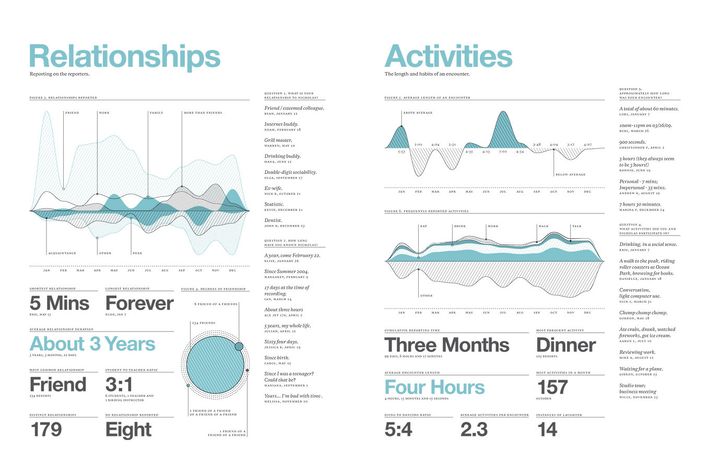

When emotional data goes beyond practical questions (When will we break up? Does my job make me happy?), the result may become something unexpectedly beautiful rather than obviously useful: a portrait. For the last eight years, designer Nicholas Felton has created an annual Feltron Report, visualizing his life in what the New York Times’ Nick Bilton once called “a poetic haze of information and well-designed storytelling” that “blurs the line between art and data.” Felton’s data sources have included Netflix, iTunes, GPS tracking, Flickr, and detailed personal notes. In 2009, he asked “friends, family, co-workers, and acquaintances” to “report on his activities whenever they met.” He had 4.8 interpersonal encounters per day, with people he had known, on average, for 3 years, 3 months, and 22 days.

Once a cult obsession, Felton’s personal data poetics went mass when Facebook hired him to help build its Timeline feature. By automating the information-condensing process, Facebook enabled those who lack Felton’s discipline to view the sum of their data as an evocative personal history. Facebook VP Chris Cox cited the Feltron Report as a Timeline inspiration: “Fourteen pages. One year. One book. It was hard to call it anything other than what it really was — art.”

Though the average Facebook user may not view her profile as art, Harvard Berkman Center fellow Judith Donath places the “data portrait” in an art-historical context in her forthcoming book, The Social Machine. Whereas medieval portraits signaled the subject’s status through symbols and poses, in the Information Age, portraiture often arises from recordings and data. Self-representation is prominent “to a large extent out of necessity,” Donath explains by phone. “In a physical world, you exist without a portrait. You just go out and you have your whole body. Whereas without some kind of portrait online, you don’t have very much existence, there’s just not very much stuff around you.”

A data self-portrait could be as small as a two-line message board signature, but as the portraits expand to Feltron Report magnitudes, they resemble the meticulously personal works of some contemporary artists. Donath considers Tracey Emin’s Everyone I Have Ever Slept With, 1963 - 1995, a tent appliqued with the names of 105 bedmates, to be “a forerunner to the social network portrait.” Artists who pair portraiture with inventories — like Rachel Strickland photographing the contents of gallery visitors’ bags — create “physical data portraits.” Compare those portraits to women who display and tabulate shopping trips in “haul videos”: Displayed in aggregate, the collections define the person through the variety of objects accumulated.

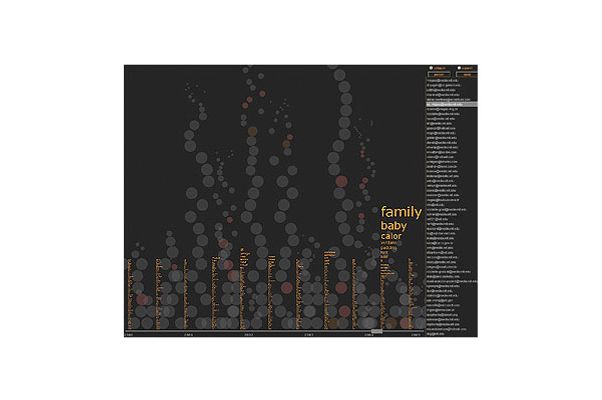

Quantified Selfies offer the chance for self-discovery, too. Because digital data is vast and immaterial, viewing the aggregate can be difficult, and the process of organizing information can reveal unexpected truths. Donath recently led a team of MIT Media Lab researchers in the creation of several data portraiture methods. A program called Themail organized users’ e-mail archives into visual and thematic timelines for various e-mail relationships. “Each e-mail itself looks like every other e-mail,” Donath explains. “A little e-mail from the IT department saying there’s going to be a server shutdown tomorrow is going to have the same physical form as an incredibly intense breakup e-mail, or an ‘I want to marry you’ e-mail. That affects our ability to form memories around them.”

When users tested Themail, they found patterns that sometimes jogged or altered their memories of relationships. “Just about every one of these columns has the word please,” one user said of a Themail visualization of her dance troupe’s group e-mails. “We’re all just begging each other to do stuff! That’s really what this is about.” A Ph.D. candidate noticed — and regretted — the frequency of baseball references in exchanges with his academic adviser. “I was a slacker for the first couple of years,” he lamented. His quantified Themail selfie was less attractive than he’d hoped.

Social media amusements like @Tofu_Product, a bot that scans its followers’ feeds, then tweets impersonations of them, have a similar appeal: The user learns how others might perceive her, based on the sum of her archive. The relationship equivalent could be TwitAmore, the web app that reveals Twitter love affairs by quantifying @-mentions, or Facebook’s “Couples” pages, the automatically generated Timeline spinoff for pairs.

What kind of rewards do these projects offer their creators? For one thing, access to a past that might otherwise be lost — Donath compares the task of organizing personal data into digestible forms to creating a scrapbook. “Even starting to go through [a data archive] is a huge, time-consuming project,” she notes. “I think some of the digital media hoarding is partly a reaction to mobility. If you lived a very immobile life, a very traditional village life, you might have less of a need for doing this. The past would just live with you a lot more. You’d be living in the house that you grew up in, or nearby. There would be a lot of people around who you knew because they knew you when you were little.” But today, “people feel their past is an ephemeral thing that easily slips away and nobody shares.”

The quantified selfie also promises something a little like therapy. “It lets me understand my behavior in a regulated way,” Vo says. “I think having a process to the madness helps, the same way that putting a name on a psychological term can help some people make sense of it, by categorizing it.”

“Parsing the data can help you rationalize and look at it,” Vo continues. “Now, it doesn’t necessarily make me feel better. My friend had a great analogy: ‘It’s kind of like food poisoning, you’ve just got to get through it.’” She doesn’t want to revel in the muck of heartbreak for too long, but does have a few more Quantified Breakup charts in the works. “I’ll probably do two or three more. Or maybe four or five? But then I have to look into the next step.” Will she continue quantifying her life? “My friends were like, maybe you can do dating next.”