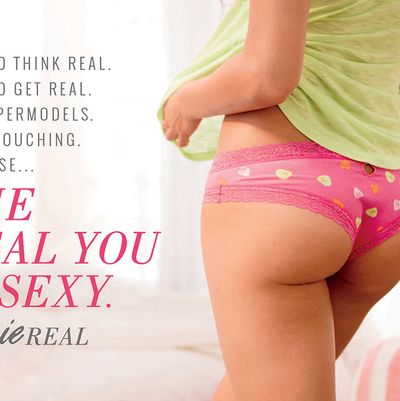

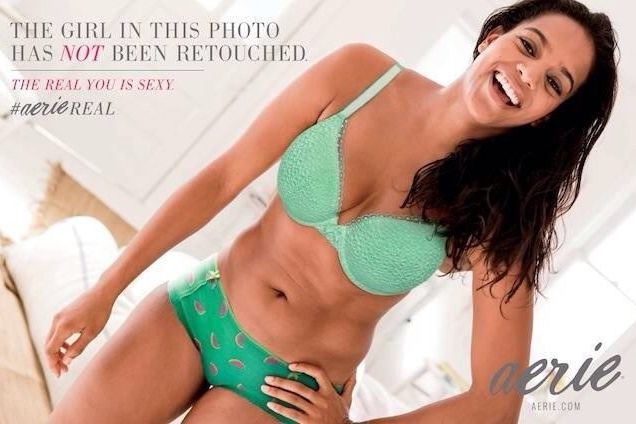

On the heels of Jezebel’s splashy hunt for unretouched photos from Lena Dunham’s Vogue photo shoot — and coinciding with the tenth anniversary of Dove’s “Real Beauty” ad campaign — American Eagle underwear line Aerie unveiled “Aerie Real,” an ad campaign featuring unretouched photos and “no supermodels.” Hailed as “revolutionary,” the ads announce, “The girl in this photo has not been retouched. The real you is sexy.” With colorful undergarments marketed at women ages 15 to 21, Aerie seems to be casting itself as the anti-Victoria’s Secret— the Jezebel to Victoria’s Vogue.

Promoting body acceptance is, at this point, a tried-and-true genre of advertising, but “real woman” ads nevertheless send me into a self-doubting spiral every time I see them. Stage One, playing into their hands: Real bodies! So beautiful! Stage Two, eye-rolling: Why do I need a panties-peddling corporation to affirm the “real me”? Am I supposed to be weeping for joy right now, like all these women who didn’t know they were beautiful until a soap brand (phonily) told them so? Stage Three, backlash-to-the-backlash: But attainable beauty standards are better than unattainable ones, right? If feminist messages sell mall merchandise, that means we’re winning. Stage Four, eyes rolling all the way around: Even if it’s pro-woman, it’s still patronizing.

Aerie, Dove, and their ilk are still catering to female insecurity; they’re just doing it in a feel-good way instead of an anxiety-inducing one. Like all “lifestyle brands,” they’re still in the business of selling women better versions of themselves; in this case, they’re just presenting a slightly more modern ideal than Victoria’s Secret. The “real” you is confidently sexy, even in her undies with the lights on. She’s bigger than a size two, but has no cellulite whatsoever. When she gains weight, her shape maintains an optimal waist-hip ratio. Her skin is “flawless” and she has no blemishes — probably because she’s a professional model. Amber Tolliver, the plus-size star of one of Aerie’s ads, was discovered at age 15 at an open call for Ford Models.

“I’ve been retouched in every way possible,” Tolliver reflected in an interview with Elle. “I’ve been retouched into someone that barely resembles me; it was like I was made into a Barbie. They cut out my ribcage, they shifted my waist to an inch within its life, lengthened my legs, lengthened my neck, raised my cheekbones, and filled in my hair because it wasn’t perfect enough. What they’re able to do in retouching is incredible, like they liquefy your entire body and remold it into whatever they want.”

The Aerie shoot was anxiety-inducing in other ways. “I was really tempted to go on a juice cleanse [laughs], work out in the gym twelve hours a day,” Tolliver said. In the end, she resisted: “I realized that by doing that, I’m essentially retouching without the computer.”

Unretouched photos are the ultimate female-media clickbait, offering the prurient appeal of ogling another woman’s fat and pores, under the fig leaf of feminism. I am a fan of cute panties and gratuitous nudity both— but let’s not kid ourselves about what’s going on here. This is not a feminist revolution; it’s lowbrow entertainment with a dash of feminism for flavor. Whether you’re celebrating Amber Tolliver’s midsection or gawking at Lena Dunham’s flab, the appeal is still the simple, base pleasure of staring at female flesh.

Somewhere in the process of questioning our desire to commodify skinny hot chicks, the general public concluded that an appropriate solution would be to commodify non-skinny women, too. Instead of reducing the attention we pay to women’s bodies, we came up with new euphemisms (“show off her curves”) and doubled down. Critics say it’s not enough for Mindy Kaling or Melissa McCarthy to land on the cover of Elle — they need to be stripped naked and their bodies need to be displayed, just as skinnier bodies are. “The implication was, ‘What, Elle, you can’t put her big, fat body on the magazine?’” Kaling later joked. “’Why? ‘Cause she’s just fat and gruesome? Why can’t we look at her beautiful fat body?’”

A better question would be: Why can’t we just not obsess about bodies? I ask that in earnest — it’s possible that we actually can’t stop, that this compulsive corporeal scrutiny is some sort of biological imperative, or species-wide neurosis left over from millennia of treating women as chattel. In the meantime, here is what the third-wave thong-positivity movement hath wrought: a Kickstarter campaign for a panties screen-printed with NO MEANS NO. What started as a Victoria’s Secret-themed rape joke has morphed into a legitimate consumer opportunity to wear hot-pink panties with visual puns about sexual consent.

I actually find these panties pretty funny, and support anyone who gets a sick thrill out of forcing her hookups to solve a rebus puzzle stamped on her crotch. (“C’mon, sound it out. Mustache. Must … ask …”) To call this a revolution, though, is insulting to revolutions and panties. The former is important because it needs to be; the latter is meaningless because it can be.