In the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, the Southern Californian photographer Jo Ann Callis made a name for herself as a pioneer of fabricated photography. Though less well known than some of her successors (Cindy Sherman, Laurie Simmons, Gregory Crewdson), Callis was one of the first photographers to work extensively with constructed sets, arranging models and tactile objects in ambiguous, often unsettling tableaux. In 1981, her work was included in the Whitney Biennial, and has since been widely exhibited at MoMA, MoCA, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Getty.

As suggested by her focus on the domestic sphere — she’s best known for her dreamlike interiors and uncanny still lifes — Callis’s trajectory as a photographer is a bit unusual. Born in Ohio in 1940, she was married with two children by the time she was 23. It wasn’t until her early 30s that she completed her undergraduate degree UCLA, where, under the instruction of the legendary photographer Robert Heinecken, she first learned to use a camera.

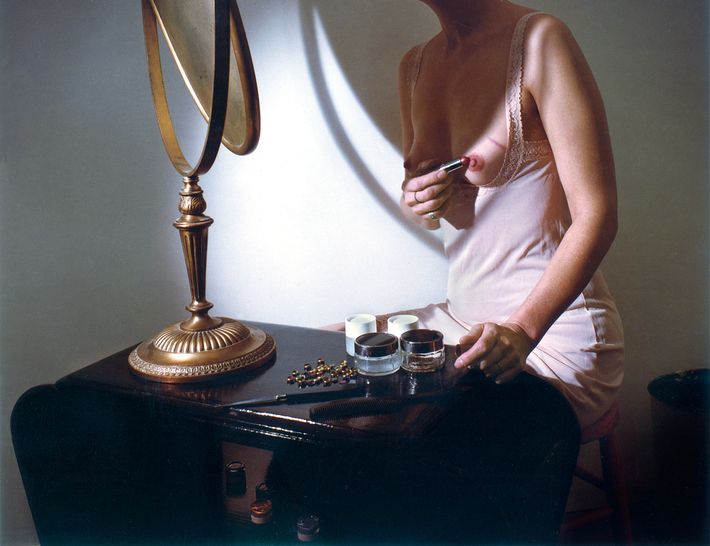

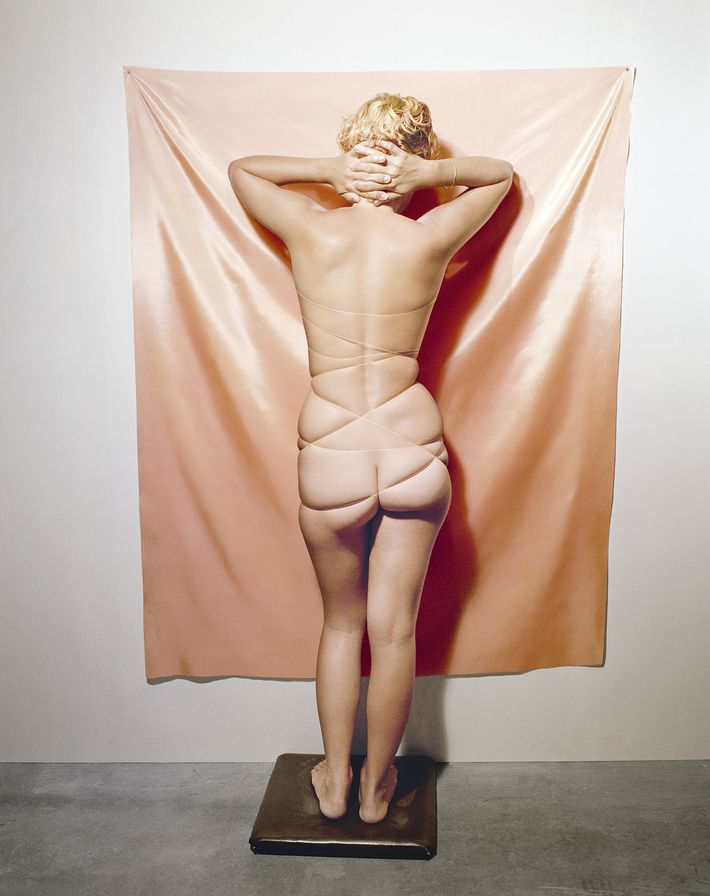

She continued to study under Heinecken for next three years, who encouraged her to work with sets and props to create staged scenes. “I was trying to get out of my marriage and get a divorce, and the time was such that everyone was trying all kinds of experimentation,” Callis told the Cut. “I wanted to set things up, I wanted to make a world of my own.” Under Heinecken’s influence, Callis spent much of her time in grad school working on what she now calls her “fetish project.” The resulting photos — an evocative collection of anonymous models in semi-erotic poses — are her most sexually explicit imagery, and the subject of her latest book, Other Rooms, out this month from Aperture.

The photos, taken between 1974 and 1977, are some of Callis’s earliest work — which she’s largely kept a secret until now. “I put them away for a very long time,” she explained. “I started working at CalArts in 1976, which was a very conceptually oriented school, so I thought these pictures didn’t fit what they might be looking for — and I really needed the teaching job.” Even more recently, in 2009, when reviewing her oeuvre for a retrospective at the Getty, Callis kept the photos under wrap. “I remember Judith Keller asking me, Are there any other pictures we haven’t seen? And I said, No, that’s it,” Callis recalled. “I just pretended they didn’t exist, because even at that time I just didn’t think this was appropriate to show at the Getty—and I didn’t think they would be interested in it.”

Recently, at the suggestion of collectors, Callis brought the early photos to Rose Shoshana, the founder of Santa Monica’s Rose Gallery, where they are now on view. Callis spoke with the Cut about motherhood, anxiety, and why she kept these photos secret for so long.

What was it about these photographs that made you feel like they shouldn’t be seen?

Well, at first I thought it was because they were too “hot.” Or they were too emotional — they weren’t cool like a lot of the conceptual work. They were very formal, aesthetic — all the things that weren’t in vogue at the time. So, that was initially why. But mostly I was just interested in other things. I went on using some of the same ideas: like tactility, how something feels, and how you can represent a thought in a photograph just using a straight negative — not putting it out of focus on purpose, just seeing what kinds of metaphors I could create. But I think it was the sexuality in them, and I just lost my nerve.

You’ve said that you never wanted your work to be overtly sexual. Why not?

Well, these pictures are the most obvious forays into that subject matter. But that theme — either sexuality, or sensuality — is used throughout my work. Even with objects, I’m looking at them in a way that I’m caressing them with my eyes — that’s how it felt, anyway. But it’s hard to put that out publicly. Now I feel a little bit less vulnerable to criticism or what people will think. I still care, but not nearly as much, since I’m just older.

Did the fact that you were already married and had children early in your career influence your approach?

It was a very difficult marriage, and I had my children very young. I was certainly not prepared — I was out here with no help and no money, and I was pretty terrified to be out here on my own. I didn’t know how I was going to support myself and my children. Especially being in art. So, I think some of that anxiety is in the photographs, and they’re also about pleasure and pain. I was just making pictures from what I was feeling, and what I was imagining.

What role does anxiety play in your work?

Well, I seem to have been born with some of that on my shoulders. I think it can run in families — I was lucky enough to get that from my mom. It’s just part of who I am, and I live with it and work with it, and it pushes me on. Sometimes it’s very useful, and sometimes I wish it weren’t there so much. It’s gotten somewhat better, but I think that’s just who I am.

You’ve titled this collection “Other Rooms.” What interests you about interiors?

It was hard to come up with a title, but interiors interest me because that’s where the action is, for me. The most important events in my life have happened inside rooms, and because I was a stay-at-home mom and wanted to be an artist, that was my world, pretty much. My studio’s always been at home — that’s just leftover from when I had small children, but it feels comfortable to me. And I think the home is a very loaded resource for all kinds of images. It’s the place we’re most comfortable, and it’s the place that can also hold the most discomfort, at times. It has those two possibilities.

Almost none of these photographs show faces. Why not?

I didn’t want them to be pictures of certain people. They’re certainly not portraits. I wanted them to look like a body or a person, but not any specific person. I was criticized for that at that time, because if you cut off the female body — and, of course, I did this with men as well — but if you cut off the body, you’re looking at them as an object, and I thought, Well, yeah, that’s right. It’s not about Jane particularly, it’s about women; and Jane’s body is useful because she’s here with me, but that’s as far as it goes.

Do you think that there’s humor in these photos?

Well, not intentionally, but when I look at them now I think there is. I don’t think I set out to make them funny, but they are kind of funny — I can see humor in them. But that wasn’t my initial intention.

Sand and Glove, 1976–77

Hands on Ankles, 1976–77

Women in Crimson Slip, 1978

Figure in Bath, 1976–77

Woman With Black Line, 1976–77

Applying Lipstick, 1976–77

Legs on Dresser, 1976–77

Nude Facing Wall, 1976–77

Hand in Honey, 1976–77