Scorned lovers, trashed apartments, late-night rendezvous at parties with cheap canned beer and cigarettes: without a keen eye, it would be hard to place a time stamp on the images that appear in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a photo book by Nan Goldin that both celebrates and mourns a specific kind of New York City lifestyle. Its agelessness, unsurprisingly, is one of its greatest assets, and at an Aperture Foundation Benefit on Monday, the enduring legacy of a book emboldened by an aesthetic of the early ‘80s will triumphantly and confoundingly celebrate its thirtieth birthday.

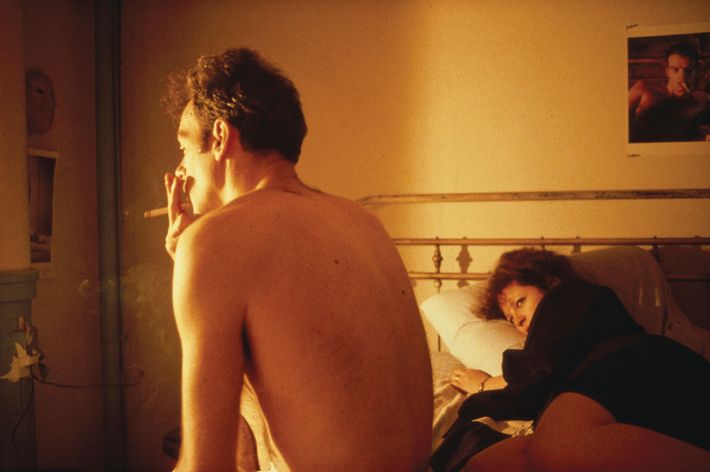

In a 2013 interview with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, Nan Goldin, then in her early sixties, explained that “there is a misunderstanding that my work is about marginalized people. We were never marginalized, because we were the world.” The work that Goldin is referring to is her career-defining book of photographs, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a collected slideshow of intimate images that explained the lives of Goldin and her friends in New York City during the late ’70s and early ’80s. She describes it with better accuracy than any admirer could, saying, “The essence of The Ballad is about the struggle in relationships between intimacy and autonomy. It’s about the dependency one can get on a person that is totally inappropriate for them.”

The images are more than that, though — they’re also a time capsule. Many of Goldin’s friends died in the AIDS epidemic, and reflecting on the photos now is like treading through a past that never quite made it into the present. When the photos were first published, they pulsed with absence, longing, and painful ambivalence, and those emotions still saturate each print today.

Goldin left behind her New York in the early ’90s to experiment with life in Europe, but her legacy has influenced hordes of subsequent artists with the desire to show life as it actually is or was. “Monique Showing Black Eye,” a well-known picture of a battered woman taken by Philadelphia photographer Zoe Strauss in 2006, appeared almost twenty years after Goldin captured her self-portrait of domestic violence, in a different city and a different environment, but the ruthlessness of both photos points to Goldin’s potent influence.

1970s New York has become the object of unlikely nostalgia: cast members of cult classic The Warriors revisited their grimy Coney Island stomping grounds this September, and Garth Risk Hallberg’s City On Fire, a novel about the 1977 New York City blackout, has captivated readers. But it isn’t just voyeuristic reflection on a city long gone that gives Goldin’s Ballad its resonance.

It’s been three decades since the The Ballad of Sexual Dependency was released but the electricity in the images has hardly diminished, and much of it has to do with Goldin’s explicit exploration of complicated sexual and emotional relationships. In 2015, we’re still exploring the indecision in sex and dating, and in a city as ever-changing as New York, to be young with lovers and friends here is still sticky, messy, and uncertain. Goldin’s images captured those feelings thirty years ago, but somehow, wonderfully, they don’t look a day over twenty-two.

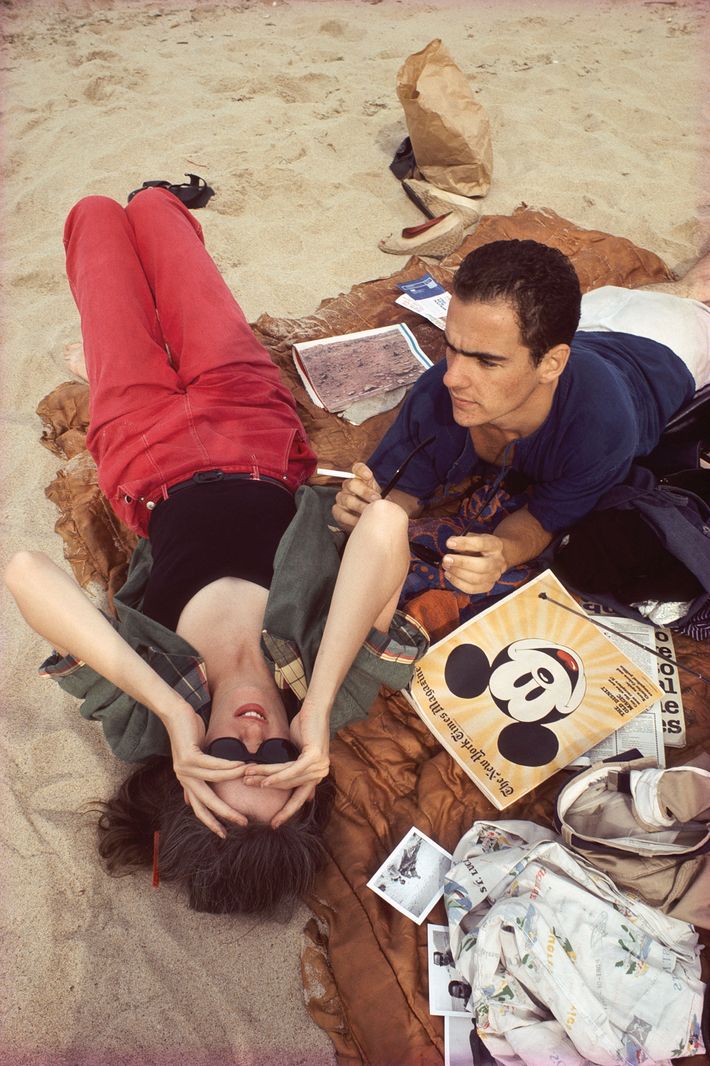

C.Z. and Max on the beach, Truro, Mass., 1976

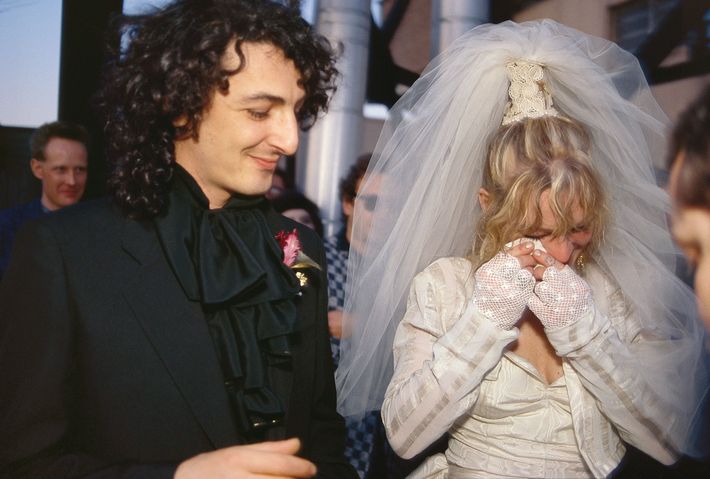

Cookie and Vittorio’s wedding, New York City, 1986

Nan and Brian in bed, New York City, 1983

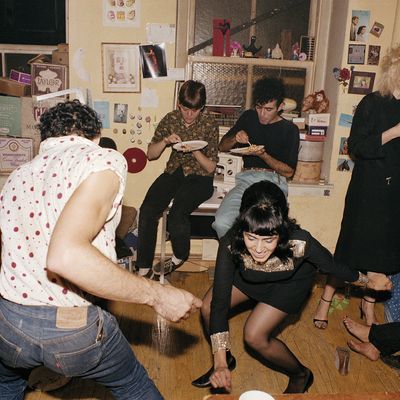

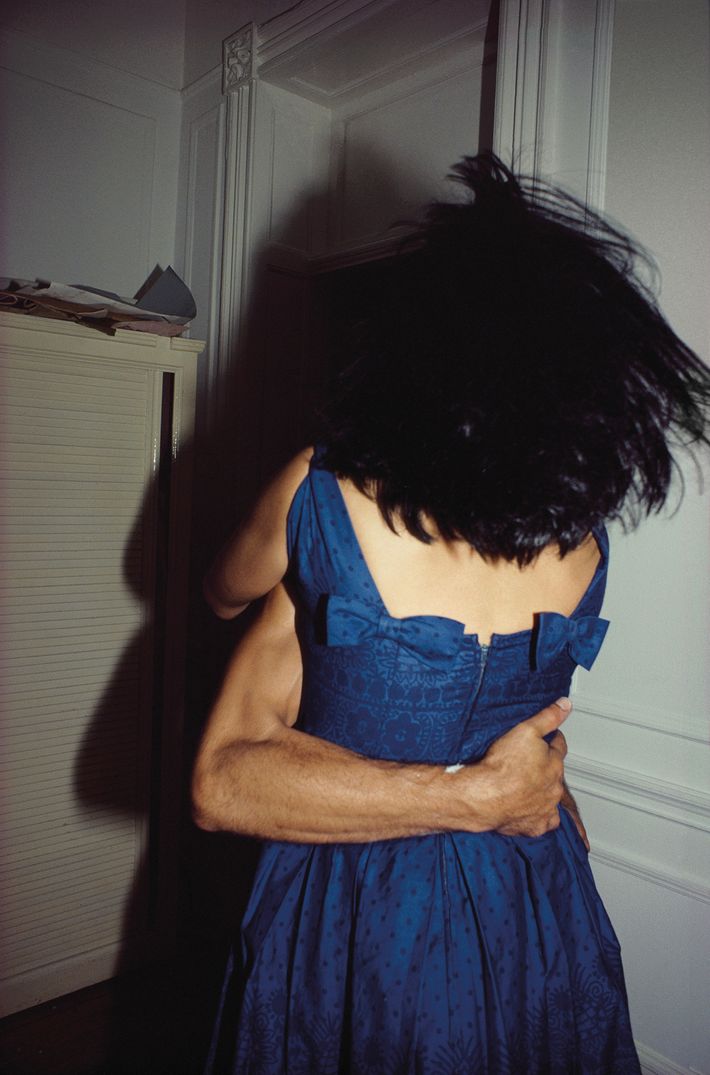

The Hug, New York City, 1980

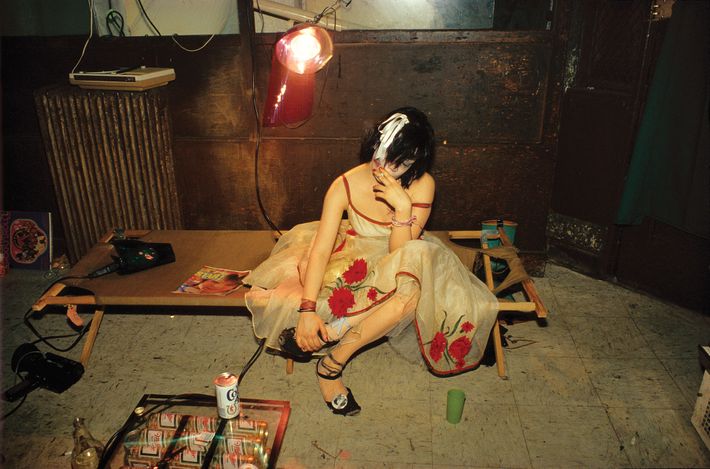

Trixie on the cot, New York City, 1979