Here’s what everyone seemed to know by Saturday: A male comedian had been accused of rape by multiple women and, after an internal investigation, banned from the Upright Citizens Brigade theater.

Although no charges had been filed and UCB hadn’t released a statement, word quickly spread through the tight-knit comedy community via social media, text messages, and private Facebook groups. Details were scarce; a message posted in several private Facebook groups for female comedians on behalf of one of the women said several others had come forward to accuse a comic named Aaron Glaser of sexual assault, and included the email of a UCB counselor that other women could contact. Eventually, another woman anonymously spoke to the press, saying Glaser sexually assaulted her years earlier. The owner of comedy venue the Creek and the Cave banned Glaser too, with the owner posting on Facebook, “If you have been banned from a comedy venue in NYC for rape, you are also banned from my venue,” adding “I will not participate in the creation of another Cosby.”

My Facebook timeline quickly filled with a stream of female comics expressing solidarity, posting reminders to “believe women,” and calling for men to act as allies to help keep female performers safe. Most didn’t name Glaser publicly, although the information was easily Google-able. Glaser initially posted a statement on Facebook denying the allegations and criticizing UCB for banning him, but later deleted the post. “I do not know who [the accusers] are, I do not know when they are referring to,” he wrote. “However, I know these are serious accusations, and I know they are untrue.”

Then men started to react.

Over the past two days, I’ve spoken with a dozen women in comedy. Every one of them had a story to tell about inappropriate conduct by a male comic. They had been propositioned, harassed, touched, heckled in a sexual manner while onstage. Some had been sexually assaulted. Many requested anonymity, fearful of potential career repercussions or simply being attacked by a mob of misogynistic trolls.

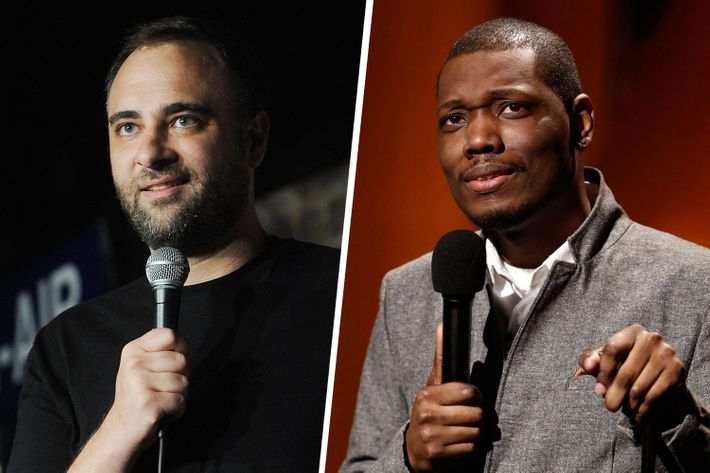

Most of them spoke appreciatively about allies in the community, about the supportive men who want to help, and those who have reached out wanting to learn. But then there are the other men, the ones like Michael Che and Kurt Metzger.

Che, a former Daily Show correspondent and current Saturday Night Live writer and Weekend Update anchor, posted a message on his private Facebook page over the weekend reading “3 different people messaged me about a comic that got banned from comedy clubs for raping girls. messaged me! CALL THE FUCKING POLICE. so the penalty for mass rape is not getting to do comedy in a club for free? way to take a stand! what fucking planet am I on?”

Metzger, who writes for Inside Amy Schumer and the Louis C.K.–created Horace and Pete despite a history of Twitter harassment, wrote a longer Facebook status on his public page, demanding the victims come forward to provide proof of Glaser’s assaults and castigating them for not filing police reports.

“The reaction of some of the guys in the comedy community is really disappointing,” says 26-year-old L.A. comedian Nikki Black, “especially when it’s someone like a Michael Che or a Kurt Metzger who has an audience and a platform that they could use for good, and they’re using it to judge the emotional reactions and actions of rape victims.”

Black, who responded to Metzger in a blog post titled “Kurt Metzger Needs to Shut Up,” says that not only does the “Why don’t you just tell the police?’ argument lobbed by both Che and Metzger discount the emotional realities of trauma, it ignores the fact that reporting a rape isn’t likely to result in jail time for the rapist.

“Ninety-seven percent of rapists never see a day in jail,” she says. “We’ve been forced to work outside the system and do things like ban people from shows because the system isn’t helping us.” (It remains unclear whether any of Glaser’s alleged victims reported the incidents to the police as well as working with UCB.)

As of Wednesday afternoon, Metzger was still harassing Black on Twitter, where he has criticized her face, hair, and tattoos as part of a tweet storm against “leftists” and “social-justice warriors.” “Ask around how well trying to smear me on social media works. I got a long history of dancing out of your bullshit charges,” he tweeted Monday. In a Facebook post Wednesday night, he apologized for offending rape victims, clarifying that his anger is against “social media mobs.”

Schumer publicly disavowed Metzger’s social-media posts Wednesday, tweeting “I am so saddened and disappointed in Kurt Metzger. He is my friend and a great writer and I couldn’t be more against his recent actions.” In a follow-up post, she said Metzger is not employed by the show, which is not currently in production.

“People don’t believe women when there’s a ton of men saying these women are lying,” Black says. “They don’t understand that every time you go to an open mic you feel like you might be in danger.”

Brooklyn comedian Mo Fry Pasic, who came up through UCB and still performs there occasionally, says men in power upholding rape culture is “par for the course” in a community that “breeds passivity” because everyone is worried about protecting their own careers.

“Women face rape culture in every aspect of their lives,” she says. “It’s important to talk about in the comedy community because these are decisions we make with our careers in mind. It’s not always based on trusting our gut but on networking and staying in good with the right people, even if the right people are abusers.”

One 29-year-old stand-up comedian and storyteller who request anonymity out of fear for her career prospects, says she was driven from the UCB community by the “emotionally unsafe” atmosphere created by the “worst kind of men” who dominated the scene. “When I was doing UCB, I was younger and was seeking a lot of that male validation, because it felt like the only option to success and feeling like you’re really a part of things,” she says.

When asked about the initial rape allegation, UCB press spokesperson Raina Falcon responded with a written statement: “The UCB is not formally commenting on this matter, but I will say that UCB has always had an open-door policy and encourages anyone with a complaint or concern regarding sexual harassment to report it immediately to any of our Directors of Student Affairs, who are trained professionals. Any such complaints are always taken very seriously.”

But some women say the “open-door policy” is PR spin. “I really don’t believe that,” says a former UCB cast member who asked to speak anonymously for fear of career blowback. A few years ago, while on a UCB house team, she says she started receiving what she describes as “creepy emails” in the middle of the night from a male UCB performer. She says that she reported the emails but administrators took no action.

“I’m very shocked that they’re taking any of this seriously, because it seemed because there’s always been creepy guys hanging around there,” she says. “There’s sort of an untouchable nature to the men around there.” She describes two incidents in recent years in which a woman alleged inappropriate sexual behavior (one on a message board and one in an online article) and were punished or reprimanded for speaking out.

Fry Pasic disagreed, saying she believes UCB does have the appropriate resources in place, but victims don’t yet feel safe coming forward because of larger cultural forces. Women who speak out about abuse are branded as victims first and comedians second, she says, while the abusers themselves are seen as comedians with some controversy around them.

A female comedian in Los Angeles says she feels ashamed of herself for needing to speak anonymously. “I wish that I believed that I could just be an angry woman in public and not be looked down on as hard to work with,” she says, adding that a woman who spoke out about sexism or abuse would be “persona non grata” in the comedy community.

She says she was once asked out by her male boss when she interned at UCB, and describes a separate instance in which a male comic put her in a cab under the guise of comforting her when she was crying, then took her to his house and tried to have sex with her.

The comic describes the disbelieving reactions of her male friends to the assault allegations as “triggering,” and says it makes her feel hopeless. “I don’t have the words to convince this other person that they’re wrong or that what they’re doing is hurtful. I don’t feel like I want to armor up about this.”

But as sad and tired as many female comics are feeling, many remain hopeful that some good will come out of the Glaser accusations. Some highlight the reactions of men who have posted messages of support on social media, who have encouraged other men to listen, and who have shared their own experiences with sexual assault.

UCB’s ban looks to many women like a step in the right direction, especially because many say that sexual harassment and assault has been ignored by the administration for years. And they feel empowered by the solidarity among women, who are drawing together to look out for one another, to work on shows together, and to fight to change the institutions they belong to.

Many of the women I spoke with write for the comedy website Reductress, which turned the painful realities into a series of articles satirizing rape culture, with titles like “I Anonymously Reported My Rape for the Anonymous Attention.”

“Being able to pitch those ideas and seeing all of these amazing funny women writing these things and using their comedic skills to subvert these assholes and this culture was so invigorating,” Fry Pasic says. “I’m thankful to be surrounded by so many women who support each other and don’t take shit. That gives me hope.”