There was a while in the middle of the 20 century when everyone — teenagers, advertisers, artists, housewives, and politicians — agreed: America had the best stuff. Records, skateboards, cars, dishwashers — these things weren’t just cool, or modern, or high-quality. They were totemic; they stood for our power and influence. We believed in the power of stuff to speak for us, to express who we really were.

Of course, it was also just stuff: empty, mass-produced, and disposable. It said more about what we lacked than about what we had.

Mike Mills, whose movie 20th Century Women just opened, was born in 1966, and he’s a self-conscious product of this era. “I kind of feel like all my art has been about what’s it like to try to figure out yourself in a consumerist society,” he told me, when I met him at his Silver Lake house. “I’ve always been trying to point out how we shape ourselves with these objects.” We load them with meaning, expect them to fill spiritual holes, only to find ourselves unfulfilled and unsatisfied. “But we’re addicted to it. It’s part of our life.”

Twentieth Century Women follows the coming of age of a Mills-like teenage boy. But it’s less about a boy and the women who made him a man than about how even the most deeply intertwined people are often unfathomable to each other, and how intense the desire to understand anyway can be. It’s about these women as seen by him. As a filmmaker, Mills is a meticulous portraitist; personal belongings, found images, and memory fragments are his chosen medium. He makes movies as though assembling artifacts in a vitrine at a natural-history museum. In 20th Century Women, his central subject is his mother circa the 1970s, and the relics he shows us are things like her Salems, her Birkenstocks, and the way she spoke to men in positions of authority. Through them, he reconstructs her style, her worldview, her history. Stuff allows him to reveal his characters as idiosyncratic jumbles of personal quirks — and simultaneously, inevitably, grounded in a particular moment. He zooms out, then zooms back in again.

Throughout his career, Mills has slipped fluidly between objects and images, art and commerce. He’s made three feature films (Thumbsucker, Beginners, and now 20th Century Women), plus a documentary about antidepressants in Japan (Does Your Soul Have a Cold?) — but he’s also directed music videos for Air, Moby, Pulp, and Yoko Ono, and commercials for Gap, Volkswagen, and Facebook. He’s designed book covers for his wife, Miranda July, and album covers for Sonic Youth, the Beastie Boys, and Air; he’s created graphics for X-Girl, Marc Jacobs, and Subliminal skateboards. He’s sold his own posters and fabrics, and exhibited his work in museums and galleries. Fluent in the language of stuff, he knows how objects can re-create a historical moment and demystify it at the same time.

“It’s not just, ‘Oh, the ’70s were great because it was more real then and these objects are more authentic,’” Mills explains. “It’s also that in the ’70s, there was such a vacuum of spirituality, of deeper thinking, that we glommed onto things in an attempt to build a world.” This was, in his estimation, “maybe more of a failure than a success.” “It would be wrong to just say I’m showing these objects because they mean so much,” he says. “It’s also because it’s the shipwreck. You’re trying to piece it back together. And it’s impossible.”

In that spirit, Mills shared a brief catalogue of objects that appear in 20th Century Women — some from his own collection, all with his own memories and associations. It’s some broken stuff washed up from the shipwreck, pieced together for clues.

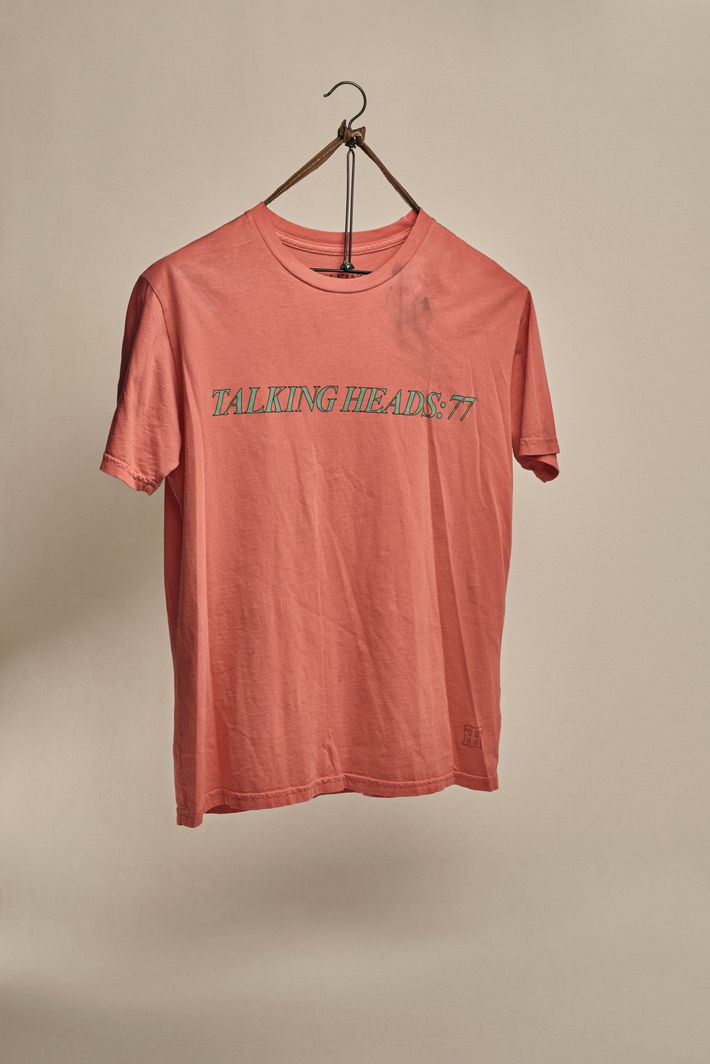

Talking Heads ’77 Shirt

1977 (Silkscreen on cotton fabric)

One of Mills’s older sisters bought the Talking Heads ’77 shirt for him in New York.

“I got beat up for wearing this shirt,” Mills says. It was a gift from his older sister, who sent it back to him in California.

20th Century Women takes place in 1979 and centers on a 15-year-old boy named Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann). Because of this, it’s easy to mistake it for a standard coming-of-age story: a boy’s sentimental education at the ministering hands of older women — in this case, his mother, Dorothea (Annette Bening); a photographer named Abbie (Greta Gerwig); and his slightly-older best friend Julie (Elle Fanning). They’re all self-contained, lonely planets orbiting one another, trying to connect through objects.

“I wore that shirt to Santa Barbara Junior High, and the coolest girl in the school — she was older, worldly, a total mystery to everybody — came up to me and said, ‘I love ‘Take Me To the River,’” says Mills. “I thought, Oh, my God, I made it.”

There’s a scene in the movie where Jamie, wearing the same Talking Heads T-shirt, schools an older boy on the female orgasm. He gets his ass handed to him for his efforts. “As a straight guy, one of my biggest fears was getting beat up. Guys fight each other. It’s one of the things you have to negotiate in the world,” Mills says. “Punk was often so macho. A lot of those L.A. hard-core bands, there was something tremendously cleansing about how fucking physical and raw and untrained they were.” But the Talking Heads promised something unfamiliar: Mills identified with their more cerebral, more creative version of subversion. “David Byrne offered a different version of a guy. David Byrne was not going to beat you up, right? He was a huge relief.”

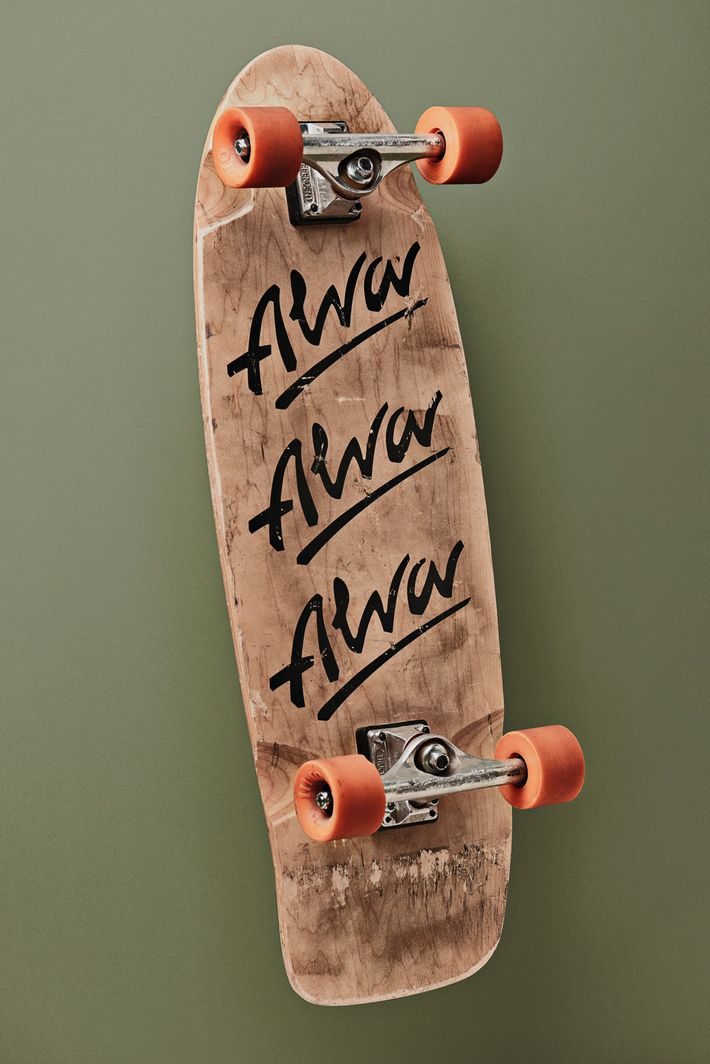

Alva Skateboard

1979 (Custom plywood, polyurethane wheels)

Alva reissued the 1979 boards; period-correct O.J. wheels added by the resourceful art department.

Before Mills and his sisters were born, his mother had flown airplanes, and she’d hoped to be a pilot in World War II — a history Dorothea shares in the movie. That past helped give Mills’s mom a visceral understanding of her son’s love of skating. She saw in skateboarding the thrill and freedom of flying planes: “She’d always say, It’s like flying.”

Mills grew up in Santa Barbara, where his father was director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art; his mother was the first female draftsperson at the Seattle branch of the Container Corporation of America. (Mills’s movie Beginners was about his father, who came out of the closet at the age of 75, shortly after Mills’s mom died of cancer.) Mills spent most of his time with his mother, and she encouraged his interest in skateboarding. Almost every weekend, she’d dutifully make the two-hour drive to take him to skate parks in Los Angeles. Hanging out in a parking lot in Marina del Rey in 1979 was not a fun thing to do — but, like Dorothea in the movie, Mills’s mom believed in exploration and self-reliance. “She was always trying to push me out in the world,” he says.

Mills might have been getting rides from his mom, but the skateboard became his vehicle to the counterculture. And anyway, his mother shared his taste for charismatic rule-breakers and his itch to escape suburban conformity. “My parents had these big dinner parties, and they were full of weird people,” he says. “My mom used to say all the time, ‘The characters are all going away.’”

The first time he heard punk was at a skate contest, and skate parks were where he first met people who seemed to be interested in “creating a way out of a lot of this bullshit.” He remembers them reminding him of Allen Ginsberg: They did not play by the familiar rules. “Growing up in Santa Barbara, I knew the normative story was such a rip-off, even for privileged, white, straight-guy me,” he says. “It just didn’t give enough emotional bandwidth. When punk came along, it was like, Okay, pain. Depression. Discomfort. Anger. Chaotic feelings that you can’t put labels on. It gave a space for all that.”

Abbie’s photos of camera, shoes, lipstick, and portrait.

2016 (Photographs of late-’70s objects on gray fabric)

Red shoes procured by costume designer Jennifer Johnson. Camera is a Nikon F2AS, purchased on eBay, that Mills gave to Elle Fanning as a wrap present.

Mills’s older sister went to art school at Parsons and had to move back to California after developing cervical cancer in her 20s. (It was the result of a drug their mother had taken while pregnant; she recovered, and — despite doctors’ predictions at the time — went on to have children of her own.) She’s the basis for Abbie (played by Greta Gerwig), a photographer who rents a room from Dorothea after getting the same diagnosis and dropping out of art school. Mills imagined these photos as something someone like Abbie might have produced around the time of Douglas Crimp’s 1979 essay on the Pictures Generation, a cohort of artists who appropriated mass-media images in their work.

Following in his older sister’s footsteps, Mills moved to New York for art school. At Cooper Union he encountered movements focused on ideas rather than art objects, like Arte Povera (“poverty art,” made from mundane materials) and conceptual art; he studied with the conceptual artist Hans Haacke, whose work posed questions about art and capitalism. Mills’s friends were involved in Gran Fury, the graphic-design arm of ACT UP.

But along with politics and institutional critique, he saw art that took a more intimate approach to consumer debris. There was Christian Boltanski’s portrait of a recently deceased woman’s every possession — all her things, transferred to a museum as though it were an estate sale — and Hans-Peter Feldmann’s nicely ordered collections of random items. Mills found their focus on random, everyday belongings human and inviting. “It was sort of exciting and open in a nice way,” he says. “I love using that technique. I find it very cinematic.”

20th Century Women is attuned to the way that curating influences and objects can become a means of self-creation and communication, of transferring knowledge and mastery — like on a mixtape. “The whole movie is sort of a mixtape,” Mills says, “from women to a man about men.” In one scene, Abbie gives Jamie a mixtape after he accompanies her to an ob-gyn appointment. She decorates the cover with what’s actually a photo of Mills’s sister, her head outside the frame. “I just love that picture,” Mills says. “You can tell what kind of woman that is.”

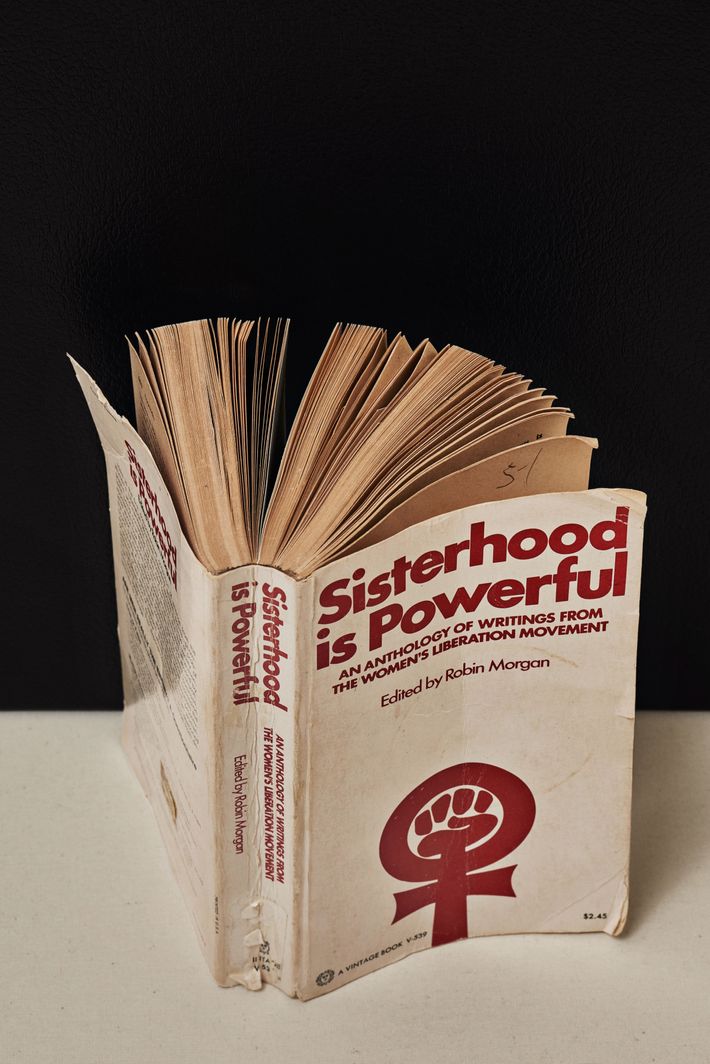

Sisterhood Is Powerful

(Paperback book; includes the essays “It Hurts to Be Alive and Obsolete” and “The Politics of Orgasm”)

One of several versions that Mills bought on eBay while writing the script.

Mills started reading Sisterhood Is Powerful while writing 20th Century Women and came across an essay by Zoe Moss about being a middle-aged woman called “It Hurts to Be Alive and Obsolete.” He began imagining what would have happened if he’d tried to read it aloud to his mother — which is exactly what Jamie winds up doing in the movie. “I was like, Holy fuck,” he says. “He’s trying to understand her so hard, and this thing would unnerve her so much. No woman wants to be seen like that, especially by her son … It became kind of central to the movie.”

Mills didn’t actually have this book as a teenager though, he says, it is totally something one of his older sisters would have given him. That, or Our Bodies, Ourselves. She liked to talk to him about how to be a good boyfriend to some woman someday, and other things he wasn’t quite ready for.

Today he sees a divide between the type of feminism that his sisters were exposed to — ’70s women’s lib, interested in sisterhood, bodies, feelings — and his mother’s. It’s mirrored in the movie by the generation gap between Dorothea and Abbie or Julie. Onscreen, Abbie is the one enlightening Jamie with second-wave literature.

His mother, meanwhile, identified more as a 1940s “working woman,” the kind of figure who might have been played by Barbara Stanwyck. As a Depression-era kid, she was comfortable with 1960s counterculture and its anti-war, anti-poverty ethos; she had a harder time dealing with things related to the body or inner life. “My mom was very, ‘I love measurables,’” Mills says. “Money and work were fine to talk about.” He was aware (as Jamie is aware in the movie) that his mom didn’t fit the feminine norms of other moms her age. “She looked pretty butch. She wore pants, had short hair, she did contracting. Her gestalt was much more like Humphrey Bogart than anything else,” he says. “She had a hard time at times being a woman, and I could see it.”

A women’s-studies course in grad school was one of his favorite classes. It offered a way to think about the politics of the personal, about “how your inner life and your identity relate to the bigger story”; as a filmmaker, he says, “that’s my hub.” Still, for Mills, feminism always returned to the question of his mother. “I think I’m sort of engineered to help Mom,” he says. It came down to “I love Mom. I want to help Mom.”

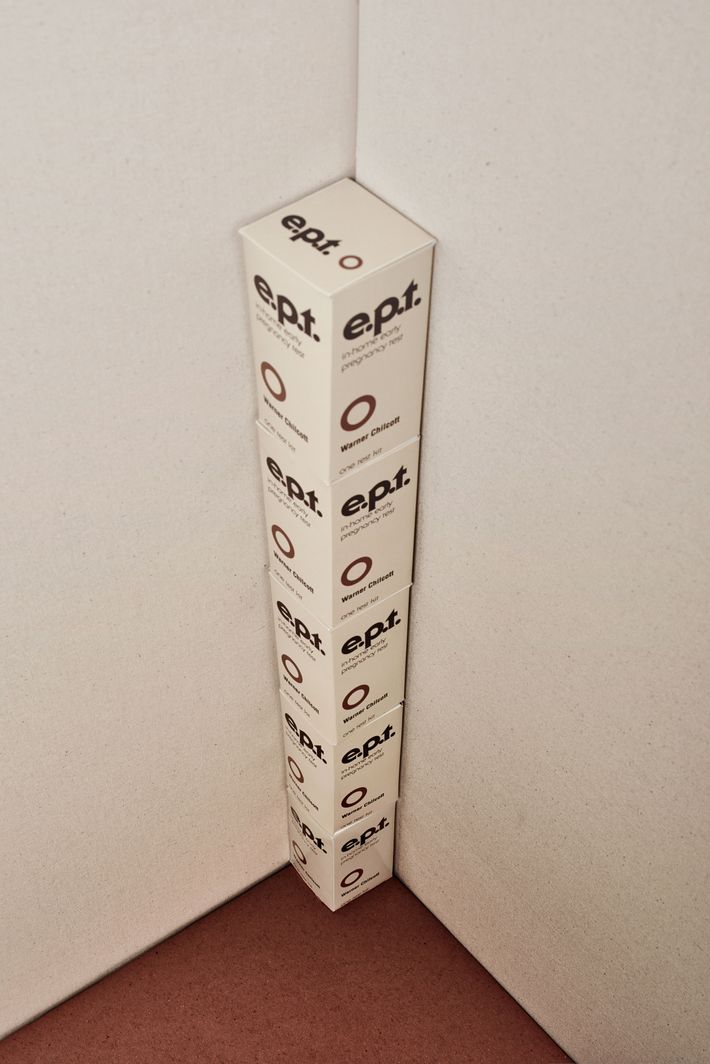

e.p.t. Home Pregnancy Test

ca. 1978 (Reproduction vintage glass pregnancy test)

Made for filming according to exact specifications.

Julie, the character played by Elle Fanning, draws on a whole group of girls Mills knew growing up. “In this particular group,” he says, “they were often very pretty and very objectified and sometimes played a performance of being simpler than they were — for power, in a funny way, and to make their lives easier.” Two of them would sneak into Mills’s bedroom at night. “I wasn’t boyfriend material, but I was friend material,” he says. “They’d go out and do this crazy shit — get loaded — then come see me and talk about it.” He got to hear how they were navigating the world of sexual liberation. “They were way more complicated than these other guys understood,” Mills says. “Both in what they wanted and why they wanted it.”

In March 1978, full-page ad for the e.p.t. home pregnancy test appeared in Mademoiselle reading: The e.p.t In-Home Early Pregnancy Test is a private little revolution any woman can easily buy at her drugstore. It looked like a chemistry set and practically required lab experience — but, for the first time, a woman could find out if she was pregnant without anyone else knowing. (That same year, Consumer Reports reviewed the product negatively, quoting a Maryland state health official who said there was “no reason” for a woman to buy such a test “unless she doesn’t want to be seen at the health department”; in other words, if she had something to hide.)

The pregnancy test wasn’t the Pill; in its own way, though, it did reflect a revolutionary understanding of women, their sexual agency, and their right to privacy. The language in the ad intrigued Mills. “It made me think of Margaret Sanger in 1914,” he says. “There’s a whole long history of Planned Parenthood back to Margaret Sanger in the movie notes.” (The ad also deftly uses the language of feminism to sell something — a now-familiar move.) Julie gave Mills a way of capturing the moment just after the sexual revolution: Julie is growing up after the Pill, after Roe v. Wade, after the emergence of women’s lib. Jamie, meanwhile, is in love with Julie, but Julie doesn’t reciprocate. Instead, she crawls in through his window every night to share his bed platonically and tell him about her adventures with other boys. At one point, she thinks she may have gotten pregnant; Jamie buys her an early home pregnancy test and helps her use it. While they wait for the results, Julie instructs him in how to smoke, walk, and seductively feign indifference like the guys she goes for.

Carved Rabbit

Mid-’70s (wood)

Hand-carved by Mills’s mother.

Mills’s mom carved animals out of wood, mostly primitive, folk-art style rabbits — in the movie, Dorothea displays them in her house. Mills’s mother loved Depression-era art for its simplicity. “Folk art was better than any art because it was more real and down to earth and democratic,” he says, explaining her sensibility (which Dorothea shares). “It was rough, handmade, and unpretentious. That was key. It was also made by people who are disenfranchised.”

The rabbits drew on her obsession with Watership Down. “I have a philosophy that — if you read it — those rabbits are so fucking persecuted,” Mills says. “It’s just one problem after the other, and it’s so harrowing, but they stay together.” He used to wonder why she loved the book so much. “My best guess is that the rabbits are like all the people who struggled during the Depression, during her childhood,” he says now. “The rabbits are endlessly dealing with external troubles, endlessly trying to make a safe home. As a piece of art, it’s very descriptive of the person who made it.” It’s a clue to the way she saw the world, but still a cryptic one.

Jamie doesn’t know his mom or Julie or Abbie as well as he’d like to: He’s trying to understand them, but can’t completely. “That’s part of the drive of the movie — this curiosity-need he has for the women that will never really get to where he wants it to,” Mills explains. Which is why he ends the movie with “Why Can’t I Touch It?” by the Buzzcocks. “He can get so close, but not as close as he wants.”

Jimmy Carter’s “Crisis of Confidence” speech

1979 (Video)

Televised presidential address on energy crisis.

In July of 1979, Jimmy Carter went on TV to discuss the energy crisis then afflicting Americans. Mills sees that speech marking the end of one era and the beginning of another. “The shit was really hitting the fan in the country,” Mills recalls. “And he, being a spiritual man, called all his people to Camp David and listened to them.” What was supposed to be an energy-crisis speech morphed into a soul-crisis speech — a speech about America’s crisis of confidence.

“Just as we are losing our confidence in the future, we are also beginning to close the door on our past,” Carter told the country. “In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.”

Carter was trying to explain “how we lost the plot, in terms of spiritual democracy,” as Mills puts it. “The presidency is like a master narrative for a writer. Jimmy’s narrative was very sketchy and postmodern, really.” He acknowledged the uncertainty of his moment, and how little we knew what might come next.

We didn’t see science and technology revolutionizing our lives the way they did, for example, but it was all starting then. “Apple went public in ’80,” Mills points out. “For a long time, I had more stuff about Apple computers in the movie.” In fact, for a while, the script was called Oh Wow, Oh Wow, Oh Wow — reportedly, Steve Jobs’s last words. Tech has been “a huge transformation of our consciousness,” says Mills, one “we didn’t see it coming at all.” It’s mutated the disconnection and consumption of Carter’s era beyond all recognition. “We get our own futures wrong — our own biography always confounds us, as we get older and older. Really? This is my life?” Personally, politically, we feel the past reverberate while living through futures we could never have predicted. “The movie is talking about all these things that we didn’t see coming.”