I read Joan Didion’s most recent release, South and West: From a Notebook, on a poolside lounge chair at a resort hotel in Palm Springs in December. It was winter in the desert, and the air was wet with recent rain. Hiking in damp sand on trails overlooking the city, cutting down into a wash lush with blossoms, it was easy to forget that a city doesn’t belong there, or a pool either — and that all of California is years deep in a drought of unprecedented length and ferocity. It was easy, too, to forget that, a few months earlier, the United States of America had elected a president who, instead of concerning himself with this fact, was preparing to repeal legislation regulating coal runoff into rivers and streams.

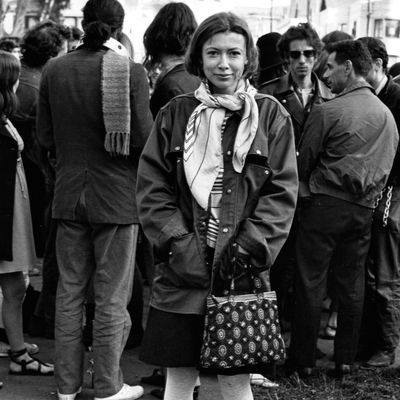

This is how I imagine Joan Didion telling you the story, anyway; this is the way her language colors mine whenever I have been reading her work. Didion’s style is intoxicating — as in, seductive and thrilling, but also pervasive, and unsettling. It is her signature to insert herself into her critical writing, to establish geographic particulars and insinuate atmospheric dread. Didion herself is famously beautiful, or at least glamorous-looking, and equally famously troubled. Her favorite subjects very often exhibit both qualities as well.

This combination of fixations worked for her through most of her career: in her iconic essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem, and its follow-up, The White Album, as well as in her fiction, in novels from Play It As It Lays to The Last Thing He Wanted. The range of her interests — from flower children getting high on Haight Street to the lives of Cuban expatriates in late-’80s Miami — gave the subjectivity of her observer’s eye something more universal to fall on, and lent journalistic weight to what it saw.

Of course, some critics have always questioned Didion’s stylishness, no matter its subject — Pauline Kael once famously dismissed Play It As It Lays as laughably self-indulgent and “ridiculously swank.” Barbara Grizzuti Harrison’s 1980 essay “Joan Didion: Only Disconnect” begins “When I am asked why I do not find Joan Didion appealing, I am tempted to answer … that I am disinclined to find endearing a chronicler of the 1960s who is beset by migraines that can be triggered by her decorator’s having pleated instead of gathered her new dining-room curtains.” For years, though, Didion was near-universally acclaimed, perhaps because she was able to describe her neurotic inhabitation of an incredibly privileged life with such unnerving intensity that the privilege receded, and all you felt was her fear.

Then true tragedy struck — twice. Didion’s husband died at the dinner table; her daughter passed away a few years later. Didion wrote The Year of Magical Thinking about his death and Blue Nights about hers. Magical Thinking was well-received, Blue Nights less so.

This was, in part, due to a shift in the larger critical conversation, which by 2011 had regularly begun to include discussions of the privilege of class — always an easy hit with Didion, but particularly noteworthy in Blue Nights. Rachel Cusk wrote in a review for The Guardian: “In The Year of Magical Thinking, the countless references to fame and social privilege have a second passport, as it were: they are an indelible aspect of the life Didion lived with her husband, and by enumerating them with such repetitive insistence she was also, in a sense, cataloguing the effects of her 40-year marriage. In Blue Nights they are, again, omnipresent, but the effect is altogether more troubling.” John Banville’s largely laudatory review in the New York Times pauses for a paragraph on her love of brand names (“Christian Louboutin shoes, cakes from Payard, suites at the Ritz and the Plaza Athénée in Paris, the Dorchester in London”).

Didion compounded public anxiety about her status as a rich, old white lady (as opposed to a serene, ascetic intellectual) by appearing in an ad for Céline. It features a close-up, flash-lit shot of Didion in a high-necked black sweater and dark sunglasses: a defiantly unsexy, legibly “classy” shot that confirms Céline’s status as a thinking-woman’s brand — and Joan Didion’s image as a particular kind of rich-and-stylish-woman’s writer. It was in itself a small thing, the ad, but it occasioned a sort of reckoning among Didion’s millennial fans; it probably ultimately generated at least as many thousands of words of think pieces about style and substance as it did actual dollars of sales for the brand.

Didion is a visibly frail 82. It does not seem unreasonable to imagine that when she approached the question of a next book, she was thinking in terms of legacy. Did she want to continue being Joan Didion the institution, a woman who had outlived her husband and her daughter and perhaps her literary prime? Or could she find a way back to the raw, searching voice that had captivated us in the first place?

South and West is an impeccable return to form, and this is, in part, because it is an actual return: The bulk of the two essays that comprise the book are drawn, as the subtitle suggests, from notes on essays Didion tried and failed to write in the ’70s. They find her back in her most familiar and fertile territory, both literally and figuratively: California during the Patty Hearst trial, covering a West Coast socialite whose presumably empty, influenceable head got turned by revolutionaries — and then driving aimlessly through the post–Civil Rights South, noting (but never attempting to suggest a solution for or approach to) the particular contradictions of the region’s politics and practices around gender and race.

The book begins with a note from Didion, from 2006, which frames the first essay, “Notes on the South.” “John and I were living on Franklin Avenue in Los Angeles,” it says, and there she is, classic Joan, placing us suddenly and certainly in the exact location of her old street. The introduction is a spare few sentences describing how she came to be in the South in 1970 (“I had wanted to revisit [it]”) and what she and her husband, the writer John Dunne, did there (“We went wherever the day took us.”). It ends: “At the time, I had thought it might be a piece.”

She dismisses “Notes on the South” again in the essay’s closing — its last line is “I never wrote the piece.” It manages to be perhaps the most chilling sentence she’s ever composed.

Because if that wasn’t a piece, what, exactly, did you just read?

“From a Notebook,” the subtitle says, and the framing around “Notes on the South” makes it clear that Didion intends it as a disclaimer, if not an outright apology. These are not compositions, exactly, finished essays, “pieces.” Instead of a cohesive whole they are a collection of impressions and observations, snatches of scenery and dialogue. From a different writer that might feel lazy. From Didion, so famously put-together, it comes off as an unprecedented offer of intimacy: a peek into the personal chaos that precedes her well-composed work.

Didion has offered us access to the particulars of her private mental state nearly as long as she’s been writing, but those descriptions were always embedded in something finished, the admission of weakness offset by the neatness that surrounds it — the sense that even that weakness has been forced into shape, made to contribute to a point. Here, at last, Didion allows us to see her messy — or suggests to us that this is what we are seeing, anyway, since this is not, in actual fact, a notebook. It is from a notebook. It was certainly edited. Still, the gesture feels earnest. South and West reads like a fundamentally unsettled work.

The second essay, “California Notes,” is even briefer and more fragmented. “Notes on the South” takes up 110 pages of my copy of South and West; “California Notes” a bare 18. This is perhaps because it’s a subject she’s already covered more comprehensively elsewhere, in her 2003 book Where I Was From, which the introduction says grew from her research on the Hearst trial.

The failure of “Notes on the South” is one of composure, turning written thoughts into an organized essay; “California Notes” fails, even, finally, at putting thoughts on the page. “I thought the trial had some meaning for me — because I was from California,” Didion writes. “This didn’t turn out to be true.”

The essay begins with a recitation of proper names, the kind Banville mocked in Blue Nights — of bicoastal airline flights, and the meals Didion ate on them, the types of expensive coats and hats and soaps her grandmother bought, the dresses she purchased as presents for a young Joan. And then comes this passage, essentially out of nowhere:

At the center of this story there is a terrible secret, a kernel of cyanide, and the secret is that the story doesn’t matter, doesn’t make any difference, doesn’t figure. The snow still falls in the Sierra. The Pacific still trembles in its bowl. The great tectonic plates strain against each other while we sleep and wake … In the South they are convinced that they have blooded their place with history. In the West we do not believe that anything we do can bloody the land, or change it, or touch it.

How could it have come to this?

I am trying to place myself in history.

Placing herself is Joan Didion’s specialty: From that opening line in the introduction, “John and I were living on Franklin Avenue in Los Angeles,” she is always at great pains to tell us and herself exactly where she is. She places herself in the timeline of cultural history, too; she explores America in a moment of political and social fracture. (Though in our current moment, it is hard not to look back and think that we have been fracturing almost as long as we’ve been America.)

There are three different histories in that paragraph: that of the South, where, in Faulkner’s famous formulation “the past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past”; California’s, insistently, perpetually blank; and that of the land itself, which is written not in notebooks but in fault lines and mountain ranges. It is in this final history that Didion has failed to place herself — that we are all continually failing to place ourselves.

The earth is not interested in us. We can call the ground bloody or we can call it clean; neither will change its willingness to open beneath our feet. The Pacific still trembles in its bowl.

This may not be Joan Didion’s last book, but it is hard not to read it as her last stand: the seemingly desperate admission that she has failed to write, failed to think, failed to figure. In fact, though, there is a grace in her surrender; power in naming her project, and acknowledging that it is a futile one.

Is there a more human experience than attempting to make yourself a place in the world, and finding that the world remains ruthlessly indifferent to you — despite your beauty, your glamour, your youth and then your age, your privilege, your intelligence, your finely honed best efforts? Is there a more human experience than finding the energy to make a record of that failure, a way of saying, it doesn’t matter, and it doesn’t matter that it doesn’t matter? Regardless of how or whether this figures in anyone else’s history, the impulse to record yourself, even if you’re saying nothing more than: Here I was. Here I was. Here I was.