When I was a news chick at the New York Herald Tribune, sequestered in the flamingo pink Women’s Department (as were all the paper’s female journalists in the ’60s), the male reporters I might encounter in the elevator looked straight through me, probably assuming I was somebody’s stenographer. I idolized the man behind the byline Tom Wolfe, who then wrote for the New York Magazine supplement being incubated within the Trib’s Sunday paper.

Every other week, this eyewitness would get inside the sockets of the protagonist of his story and tell us what it was like to be, say, “The Girl of the Year.” In a blink he’d shift point of view and give us a panorama of all the panting fans of Baby Jane Holzer. Next he would crawl inside the galactic consciousness of a Canadian academic and dare to suggest, in 19-bloody-65, that Marshall McLuhan might belong in the pantheon of thinkers like Newton, Darwin, Freud, and Einstein … “What if he is right?”

One day, I screwed up the moxie to ask him in the elevator, “Mr. Wolfe, what’s it like, writing for Clay Felker?”

“The Herald Tribune is like the main Tijuana bull ring for competition among feature writers,” he replied, in his gentlemanly Virginia Tidewater drawl. Then he actually looked me in the eye. “But you have to be brave.”

That was exactly the push I needed. I crossed the DMZ into the City Room, all bobbing heads of white men with crew cuts (except for Bad Boy Breslin and his tangle of black curls) and tapped on the door of the editor-in-chief. Clay Felker’s booming voice came back: “Where did you come from?”

“The estrogen zone?”

When he heard I was a grad student at Columbia, he asked me what I thought about the student “revolutionaries” up there. “What are these privileged kids revolting about? Why are they playing with violence?” I told him they felt shamed by the Black Panthers, who were actually prepared to die to expose racial oppression. Clay gave me the Wolfeian approach to telling the story: “Seek out a young bomber-to-be who’s struggling with this challenge, follow him, get inside his head.”

I followed a mild-mannered Missouri-born student, Marc, whose wife was on the radical feminist fringe and urging him toward violent activism. Marc was desperate to ride on the Panthers’ handlebars. At a glum tactics meeting after the trashing of Columbia, Marc dropped his head into his hands.

“We’ll never have a revolution in this country. Too many people are happy.”

Tom actually sent me a handwritten note in his freestyle cursive to say he loved that line. I cherished his occasional advice. For example: “Get out of the building as often as you can.” In other words, get down in the trenches with your characters and render their realities in scenes, dialogue, details of status — but DON’T make the mistake of writing in the first person; you don’t want to get in the way by having to establish yourself as a character. Tom didn’t yet have to worry about soiling his white linen suits in those days, not on a union salary of $130 a week. But he always stood out, with his longish silky hair curling over well-tailored tweed. Tom wrote journalism like a novelist hidden behind the sofa taking notes and recording everyone’s particular patois as it traveled down his auditory canal and struck his eardrum (like, like, KABOOM! as he might have put it).

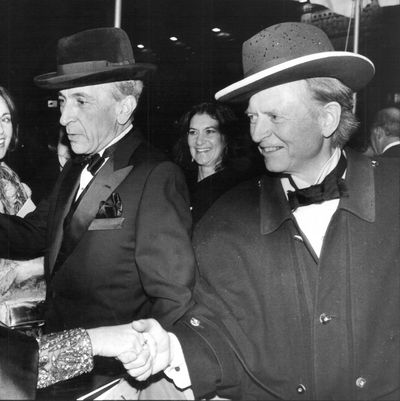

Like so many “new things,” trench reporting wasn’t all that new. Clay had first been mesmerized by it back in the Duke library, where he found bound volumes of the Civil War–era Tribune, Horace Greeley’s famous paper, and read gripping accounts of Virginia battlefields: vivid stories with narrative structure, written by soldiers in the trenches. The symbiosis between Tom and Clay — both lovers of trend-spotting, bespoke haberdashery, and breaking new ground, even at the price of losing advertisers — insulated the pair from mockery by high-and-mighty novelists and stock journalists alike, not to mention the multitude of victims of Tom’s satirical wit.

Although Tom rarely let his politics show, he was not a social conservative; he had a sincere concern for the poor and underprivileged. But he couldn’t help himself from exposing the hypocrisy of the wealthy celebrities and “social X-rays” of Park Avenue putting on the airs of social-justice activists when their most sincere concern was with “maintaining a proper East Side life-style.” He put his stiletto pen right through pretensions of what would come to be known as political correctness. And this was back at dawn of the ’70s, for God’s sake!

He did so most memorably in the 1970 New York cover story “Radical Chic,” in which he exposed the comedy of manners that masqueraded in the ’60s as revolution. And he did it aboveboard! Well, sort of. He noticed an invitation on the desk of David Halberstam, with an RSVP to Leonard Bernstein. He called up and responded to a name-taker, no problem, and appeared at the fundraising party for the Black Panthers staged by Lenny and Felicia Bernstein in their penthouse duplex. Tom even politely introduced himself to his host and hostess with his Bic pen and reporter’s pad in plain view. He was proud of being falsely accused by a Bernstein family member of using a tape recorder (heaven forfend). Years later, in a tribute to Clay, Tom described his sheer delight at the scene: “No writer would have ever dreamed of a bonanza quite this rich.”

In our new era of dazzlingly rich potential bonanzas for journalists, I mourn that we won’t have another cover story or grand comic novel by Tom Wolfe to look forward to. He was at his peak when he wrote A Man in Full, a monumental study of a protagonist like a southern Trump. Charlie Croker was a narcissistic, megalomaniac Atlanta real-estate developer whose empire was tumbling toward bankruptcy. A sequel with a Manhattan-inspired protagonist would have had to be called A Man Full of Himself.