Guests at the Met Gala are encouraged to dress in keeping with the exhibition’s theme. This year’s was “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” and most who wished to signal Catholicism did so through jeweled crosses and gold halos. Rihanna, taking opulence to its papal extreme, arrived in a sparkling minidress and miter.

Penny Martin, the editor-in-chief of The Gentlewoman, attended the gala as the guest of Tory Burch. The Gentlewoman is a biannual women’s magazine first launched by the Dutch founders of Fantastic Man; Martin was the rare editor not employed by Condé Nast to make Vogue’s guest list. She wore a vintage black Yves Saint Laurent dress (high neck, bell sleeves) and a black Céline evening coat. It was a look that might be described as Our Lady of Immaculate Taste — or, perhaps, as faintly Protestant.

The Gentlewoman is a magazine about taste: Restraint is one of its tenets; another is respect. The Gentlewoman’s subjects and readers alike seem dignified because Martin treats them with dignity. Taste, in her magazine, becomes a kind of virtue. At the Met Gala, Martin had felt “quite European and quite classically nunlike,” she told me the next day, if perhaps also slightly out of place. To some extent, her discomfort was a transatlantic thing. “Black tie in America is so much more formally observed than it would be in Britain,” she said. “To try and imagine oneself in that way — most of my friends wouldn’t, because they’d feel like they were at Ascot Ladies’ Day.” Americans, meanwhile, “are brought up in the court of Disney and of Hollywood, and in fact, they can wholeheartedly throw themselves into that persona without feeling that they’re an impostor.”

In this sense, it was also the Gentlewoman thing. “When you represent a magazine that’s meant to be about feeling comfortable in yourself, you don’t want to suddenly feel like you’re donning a costume,” Martin explained. She had felt like herself.

The magazine Martin has edited since 2009 is a sturdy, handsome object.

Between its soft, pebbled covers, on alternating matte and glossy pages, photographs are printed richly enough that you can feel their shadows against your fingertips. These photographs, and the words that accompany them, articulate an alluringly elusive vision of aesthetic rectitude. Since its first issue — which had a rosy-beige cover years before everything turned millennial pink — The Gentlewoman has amassed a cultish devotion among stylists (for its witty approach to clothes), graphic designers (for its Dutch and German rigor), and magazine enthusiasts generally (for the playful affection with which it approaches the form). The Gentlewoman No. 1 now sells for hundreds of dollars when it appears on eBay. While the magazine’s circulation is modest, about 99,500 per issue worldwide, it is a fashion-world darling whose devotees stress that its appeal is hardly limited to the world of fashion. “I know plenty of people that aren’t super-duper interested in Céline sweaters but who love The Gentlewoman,” said Jessica Diehl, the former creative director of Vanity Fair.

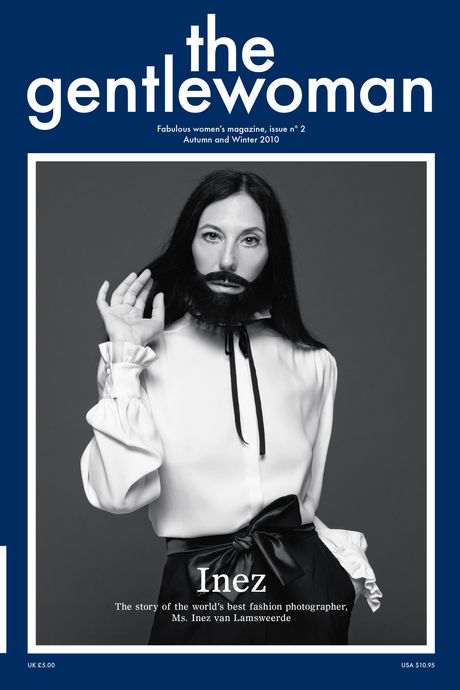

“I think The Gentlewoman is really the only women’s magazine that matters,” the photographer Inez van Lamsweerde told me. Van Lamsweerde is a glamorous figure in her mid-50s with large eyes and a cape of long black hair. She and her husband, Vinoodh Matadin, take photos for magazines like Vogue, Vanity Fair, W, V, T, and i-D. Van Lamsweerde herself appeared in The Gentlewoman’s second issue, profiled inside by Martin — the cover was a self-portrait in which she wore a high-collared Chloé blouse and a black beard.

I met Martin for the first time at the Grand Central Oyster Bar, which The Gentlewoman’s editorial assistant had described as Martin’s favorite place in New York. The choice had surprised me — dowdy midtown, with the commuter rail rumbling nearby — but only at first. The Grand Central Oyster Bar, with its Beaux-Arts–meets–’70s-rec-room interiors, is a lunch destination that seems of a piece with The Gentlewoman’s other tastefully unexpected recommendations. (These include salty licorice, bar soap, and carrying a folding clothes hanger to hang your coat in restaurants.) Martin arrived in practical attire — a Levi’s jean jacket, a gingham collared shirt, and white Reebok sneakers. She had walked from her hotel in the West Village. After asking the waiter which ones would be sweet and milky, she ordered Lady Chatterley oysters from Prince Edward Island. Grand Central had an additional advantage, she told me: It isn’t far from the main branch of the New York Public Library. Martin hoped to visit the Picture Collection archives housed there to see if they had any undigitized clippings that might provide footnotes or marginalia for the Agnès Varda profile in the magazine’s fall issue.

When she met Martin, van Lamsweerde said, her first impression was of someone “almost too nerdy for the fashion world.” And yet, “things that we only feel, she knows how to put them into words,” van Lamsweerde said. “She makes fashion look good, like in terms of its intellectual side.”

Martin was once a Ph.D. student in the history of design, and the thesis she never finished concerned Thatcherism and the British Vogue of the 1980s. It was during that time that advertisers began to pursue the so-called moving target, an industry term for the elusive working woman — who, in the pages of Vogue, Martin saw “striding down the street with a briefcase in front of Lloyd’s of London.” Anna Wintour, as British Vogue’s editor during this period, figured prominently in Martin’s project. Martin first got interested in Vogue before leaving for university; today she has a collection that dates back to the early 1960s. When she was at work on her doctorate, most

of her peers regarded the photos she was studying as “deeply unfashionable,” the “absolute apotheosis of neoconservative image-making.” Yet they fascinated Martin. They were, in their way, photos that strove to depict women in motion, women as people who do things. “I wouldn’t say that our politics or our image-makers or even our tastes are the same,” she explained — but she sees the magazine’s influence in The Gentlewoman.

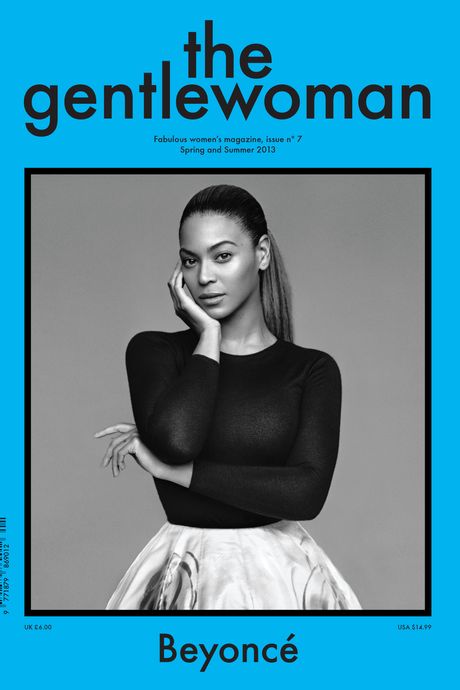

The working woman of ’80s media tended to be a vague specter, a collection of clichés and fantasies rather than a particular human being, but the women whose profiles and interviews give The Gentlewoman its backbone are resolutely specific. Sometimes they are famous but not always. Sometimes the cover subjects are famous women who don’t often appear on the covers of women’s magazines — like Angela Lansbury or Zadie Smith. Women you might assume to be familiar, meanwhile, often reveal themselves afresh. Beyoncé appeared on the cover of The Gentlewoman No. 7, spring/summer 2013. The magazine had worked with her U.K. publicist previously on profiles of Adele and Sinéad O’Connor, and, uncharacteristically, Beyoncé granted the magazine an interview. That same season, she was on the cover of both Vogue and GQ. For Vogue, she’s a wax-statue First Lady, coiffed and powdered into bland propriety; for GQ, she’s golden, a Terry Richardson pinup, underboob peeking into view. Meanwhile, on the cover of The Gentlewoman, Beyoncé wears a crewneck black sweater and a ponytail. She looks like the most beautiful person you might actually know, caught looking at herself in a mirror.

If the default tone of much celebrity journalism today is Tom Wolfe Lite — everything wild, everything a circus, the subject outlined in neon hyperbole — The Gentlewoman’s approach is the opposite. The magazine renders women ordinary and more appealing for it. The women talk in great detail about their work (in retail, architecture, or conceptual art), wandering freely into the weeds. They are interesting because they’re permitted to risk being boring, which feels somehow like a luxury. It’s a relief. The reader absorbs their confidences like overheard conversations in a quiet restaurant — unfamiliar but intimate and engrossing. The Gentlewoman “has always had what I think now has become a little bit of a commodity,” Vanity Fair’s Diehl told me. “Before it was something that everyone talked about, it’s always been about the female gaze.” In its pages, women contemplate one another as peers.

Notably, the women who populate the magazine are adults. There’s a range, but many seem to cluster in their 40s and 50s. “I was never that interested in youth, even when I was young,” Martin said. “I just was desperate to be an adult woman. I used to listen to my mum and her friends and hear them talking about divorces and watch Dallas with them.” Youth, through the lens of The Gentlewoman, seems somewhat obvious, a little cheap.

What is a gentlewoman, for the purposes of The Gentlewoman? Martin’s editor’s letter from issue No. 1 offered a working definition. The magazine’s subjects would be “stylish, intrepid, and often hilarious” contemporary women, and they would be depicted in journalism and portraits that reflected “women as they actually look, sound and dress.” In contrast to “the passive and cynical cool of recent decades,” Martin wrote, “The Gentlewoman champions the optimism, sincerity, and ingenuity that actually get things done.”

In some sense, Martin embodies this spirit. “She is the brand,” Diehl said. Martin sends thoughtful letters and presents, charms strangers, and talks about concepts like dignity and respect. She is her magazine’s best ambassador. But if the word gentlewoman conjures staid, upper-crust propriety, then in this sense the fit is less secure. Martin, who is Scottish, still remembers the challenge of learning to navigate London manners. (There is also, she points out, “a very big political difference” between the Scottish and the English; the Scottish are much more left-wing. Later, when I asked her about her own politics, she told me, “I’m a socialist, of course.” She added that she should probably be careful — words mean different things to different international audiences — but “it just seems like common sense to me.”)

Born in Glasgow, Martin grew up in St. Andrews; her mother was an art teacher, her father a musician (they separated when Penny was 13). Martin was the oldest, with two younger brothers — a third had died as a baby — and they were close. She didn’t read fashion magazines back then, but she did look at her brothers’ copies of Thrasher, plus the weekly music magazines — Melody Maker, NME, and Sounds. Music was the main thing as a teenager in St. Andrews. “There was no kind of honor in walking around in 1988 wearing Versace,” she said. “We were much more proud to have a completist record collection and wear band T-shirts.”

Martin went to Glasgow University and studied art history, then did a museums course at Manchester University. It seemed “very clear” to her that she was going to be an academic. In 1998, she moved to London to study at the Royal College of Art and work as a curator at what was then called the Fawcett Library (now the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics). In 2001, her 25-year-old brother, Ryan, was attacked on the street in Glasgow and afterward died of a head injury. Martin was 28 at the time. Bereft, she decided to take a year off from her studies. About three months into that first year after his death, she got a call from the photographer Nick Knight. He’d heard about an exhibit she curated at the Victoria and Albert Museum, breaking down a single issue of British Vogue from catwalk sketches to ads. He wanted her to be the editor of his new website, SHOWstudio. “It was kind of a gift from God,” Martin told me. “There’s lots of negative things to say about fashion, but when it’s going well, it is the sunniest place on earth.”

SHOWstudio was an early pioneer of fashion photography online, and she’d been there for seven or eight years when Jop van Bennekom and Gert Jonkers, founders of the magazines Butt and Fantastic Man, approached her about starting a women’s version of the latter. They had meetings and long conversations, brainstormed, and compiled lists of the women they wanted to include. Martin looked up titles of defunct magazines in the Women’s Library — one, from the turn of the last century, was called The Gentlewoman.

Martin thinks now that she pursued an academic career for so long because it felt like the responsible thing to do. “I thought I wasn’t in a position to be fanciful about my future,” she said. “I came from a single-parent family who got free school meals.” Growing up, she had the private sense that she shouldn’t burden her family with any failures or delays. “I was doing art history; it wasn’t like I was down the mine. But I definitely felt like I owed it to my mother that had made a lot of sacrifices to make sure I made a success of it.” It wasn’t until later, after Ryan’s death, that “I realized that pleasure could be anything to do with my working life.”

Yet in contrast to the cartoon hedonism sometimes associated with the fashion world — or at least with fashion photography — pleasure in The Gentlewoman tends to be something idiosyncratic and cerebral. Certainly this is true of the magazine’s visual language, which refuses the obvious glamour of indulgence. Early on, Martin told me, they used to joke that there was “no sex in The Gentlewoman” — indeed, the magazine can seem like the inverse of Butt’s exuberant gay male sexuality. In place of sex, The Gentlewoman tends to focus on the sensual pleasure of fashion itself. Textiles and leather are shot in tightly cropped close-up, reduced to their sumptuous textures. Shoots adhere to what Veronica Ditting, the magazine’s art director, calls a “no-fantasy-fashion policy.” These are the pleasures of an immaculately tasteful life: of custom-tailored pants, of an esoteric snack,

of a quiet gallery. This, I think, was roughly what Inez van Lamsweerde meant when she told me that the magazine’s style was rooted in women’s experiences — “and it makes me want to buy the stuff that’s in there more.”

The first woman to be profiled for the magazine’s cover was Phoebe Philo, who, at the time, had recently shown her first collection for Céline. Philo would go on to shape nearly a decade of women’s fashion — she left Céline earlier this year — and she very rarely speaks to the press. “Phoebe did me a very big favor in doing that first interview,” Martin said.

She had previously interviewed the designer in 2005, while Philo was still at Chloé — her tenure there had been a critical and commercial success, but when they spoke at that time, Martin sensed something amiss. “It was very clear to me during the interview that she was about to leave,” Martin said. “She was depressed as hell.” Martin knew Philo’s agent, so she gave her a call to see what was going on. “Is she trying to tell me this as a scoop, or does she not know what she’s told me?” Martin remembers asking. “Because it’s very obvious she’s not happy and she was very, very forthcoming — you know, too forthcoming.” The agent called her back after speaking to Philo. She asked if Martin could please keep that news to herself, which she did.

Restraint — perhaps The Gentlewoman’s central tenet — paid off. When Philo’s representatives offered Martin The Gentlewoman interview several years later, it was “a really charming gift,” she said. “Because it was the imprimatur of the woman that would be very associated with our early aesthetic — or rather, we would be associated with hers.” Today, with Philo departed from Céline, The Gentlewoman remains as a cloister for the acolytes of good taste.

*This article appears in the October 29, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!