For almost six decades, Calvin Trillin has been a journalist, writing for The New Yorker, The Nation, and early on, at the short-lived magazine Monocle. He covered the school-integration movement in Georgia, and wrote a long running New Yorker column about America, including a lot about what he was eating in America; some of those essays, many of them featuring his wife Alice and daughters Abigail and Sarah, would later be compiled in popular books including Alice, Let’s Eat, and American Fried. Trillin also wrote a book about the difficult path of one of his closeted college friends and published several satirical novels, including one about parking, Tepper Isn’t Going Out. As he would write in the dedication to that book, nearly everything he composed was written with one reader in mind: Alice.

Alice Stewart Trillin was a writer and educational television producer who battled lung cancer in her late 30s, surviving it and going on to write about the experience, including in a 1981 New England Journal of Medicine article called “Of Dragons and Garden Peas” that was taught for years at medical schools. She died at 63, in 2001, of heart failure precipitated by the intense chemotherapy treatments she’d sustained in her 30s. Five years later, her husband published a stunning remembrance of her in The New Yorker, aiming to present a fuller version of the woman he’d often deployed in his essays as a buttoned-up straight-man — the George Burns character — to his zany and omnivorous Gracie Allen. Trillin would later expand that essay into a short and gorgeous book, About Alice, which has now been adapted for the theater. This month, it is being performed as a two-person play at Theater for a New Audience.

I spent a morning with Trillin, who is 83, in the Greenwich Village townhouse that he and Alice bought in 1969, talking about the process of working in collaboration rather than editorial solitude, about the experience of seeing himself and his late wife brought to theatrical life, about having become a benchmark for true love and admirable hetero male behavior in an age of acknowledged toxic masculinity, and about the objects around him that still evoke his beloved partner.

Rebecca Traister: You write so much in your recollections of Alice about how the impetus for that writing was taking apart the cartoon character version of her, and of your marriage, that you’d presented in your earlier work. What is it like to see Alice made into an actual dramatic character on a stage?

Calvin Trillin: Well, I guess that was one of the reasons I did it, that I wanted her to be heard more.

Almost everything she says in this play is partly to the audience and partly to me. And almost everything she says to the audience are actually her words from her letters or essays. A writing course motto is “Show don’t tell.” And memoirs almost completely tell, and this was a way of showing her. Also there was just sort of a corrective feeling to it, it was a way of presenting her as really a substantial person, not what I call “the George Burns character” in the book.

RT: How much did you talk with her, when she was alive, about your, and her, anxieties about presenting her as only the George Burns character, or about writing about your family in general?

CT: There’s a scene where we’re sitting at dinner, the girls have gone up, and I say to Alice “I hope you don’t think that what you just said was off the record.” In fact, I had some conscious limits about what I wrote about Alice and the girls. I don’t think you could read everything I wrote about the girls and tell one from the other.

RT: I could, but I was a little girl when my father first began reading your pieces to me out loud.

CT: Were you focused on Sarah rather than Abigail because she was littler?

RT: No, I was focused on Abigail because she was older, and I was the older sibling, but I kept them very distinct in my mind. I must’ve been 7 or 8 when he was reading them to me, and they were really stories about the girls as far as I was concerned.

CT: That’s true as far as they were concerned, too.

I quit writing about them, not consciously, but I think the last piece I wrote was when I took Sarah when she was about 10 to the catfish festival. It’s obvious that a teenage girl doesn’t need her father writing columns about her, so that wasn’t a question. And Alice … everything I wrote about her was true. She explained things to me because she knew words like “hermeneutics…”

RT: And heuristic…

CT: Yeah, in case they were on an emergency exit or something, it’s good to have someone with you who understands what they mean. Those are gone now, those words. Fortunately we have others. We now have “heteronormative.” That did not exist.

RT: Did you have to be told what it meant?

CT: I did.

RT: Who did that for you?

CT: One of my daughters. And my grandchildren teach me. They taught me the word “extra” not used as regular old “we’ve got extra food,” but “her dress was totally extra.”

RT: Yes, I was first taught that by a young person.

CT: I like that word.

RT: Me too.

Tell me about the process of making a play.

CT: It’s different than the book, a different experience, particularly for me, because I’m not used to working with other people. I’ve got my notebook and me. So just the administrative problems: the phone call to set up the conference call to set up the meeting to set up the conference call; it’s totally different from what you do as either a reporter or just sitting there looking at the screen.

RT: Is it disconcerting specifically to have collaboration on a project that’s so personal and about bringing your marriage into vivid performed form?

CT: Well, as I say, she wrote about a lot of this stuff. I wouldn’t discuss her childhood and her father’s financial problems if she hadn’t written it herself. It is kind of weird: Today I was exchanging email with the director about one line and I said, I don’t know how to refer to myself when I’m not me. Sometimes I put it in all caps “CALVIN.”

RT: Does it feel like watching a version of yourself or does it feel like watching a character?

CT: Kind of a version of myself.

RT: Does it feel like watching Alice?

CT: I had an odd experience, I was dressing and the television was on, or the radio, I can’t remember, and I heard just the inflection of somebody talking, not what she said, and I thought it sounded like Alice, and then I realized it sounded like Carrie Paff, the actress, playing Alice, which meant she sort of got it down pretty well.

RT: Do you go back to her writing yourself all the time? Do you regularly read her pieces, her letters?

CT: I have during the play, because of the play, but ordinarily I don’t think I would. I’m pretty familiar with them.

RT: When you first published The New Yorker piece, learning from the condolence letters you received how close readers had felt to the version of Alice you’d presented in your writing, but how they never really knew her, I remember, and I wrote about this at the time, feeling slightly chastened because I was among those who felt deeply attached despite having never met her, never having known her, outside of your writing. I wonder how you feel about a whole other readership that’s now come to know her through this, and will come to know her through the play. Do you think they have a truer version?

CT: Yeah, I think it’s all together. When the book came out, maybe it was the piece or I guess both of them, I got a lot of letters saying that this was a love story, a story about a marriage, and I thought I was just writing about Alice. I didn’t set out to writing anything like that. There’s a line I wrote about how they may not have known her but they know how I felt about her. I was surprised that people knew that.

RT: Well I want to talk about that a little bit, because I went back and read, for the first time in years, your 2006 piece, which I loved so much that I wrote about it at the time. Reading it now reminded me of that time in my life, and it made me think about what it was that you expressed that meant so much to me then. And you write in the piece about the woman who wrote to you “I hope I find someone who loves me as much as Calvin loves Alice.”

CT: “I hope my boyfriend loves me as much as Calvin loves Alice.”

RT: Right. This question: is it about a marriage? Is it about Alice? Is it about how you felt about Alice? I wonder about it now because of how I felt the way about it at the time. It was a window into a version of romantic love that to me, then, felt impossibly great and personally unimaginable. I think that dynamic also feels intense in this present moment, when all kinds of bad experiences that women have with men — in dating, in marriages, at work, with sex — are being brought to light. And I think that even in the sitcom version of your early work, you communicated so much adoration and respect for Alice, such unfettered affection. That’s not only legible; for a lot of people, men and women, it comes across as extremely rare and precious

CT: You don’t know about any marriage but your own, really. So, I don’t know how many people have that sort of marriage.

Sometimes suddenly people get divorced and I’m not very good at catching emotional things between people; we would leave a party and Alice would say “Boy, you see that in there?” and I’d say “What?” “They’re obviously gonna break up.” “Who?”

So I think that I may be on the extreme side, but in fact, nobody knows what goes on in anybody else’s marriage. I was pleased at the letters, because I hadn’t written about the serious things — about her cancer, or what she did for a living or anything like that. So I was surprised that they caught the affection.

RT: It was impossible to miss. And then it’s amplified by the desire to make sure the rest of her is known and respected. In reading it again, the past few days, the passage where you say that you were desperately afraid of ever disappointing her, that you worked through your marriage to never do anything to make her regret marrying you…

CT: That’s in the play. I always thought of it as if I ever disappointed her I would just go back home to Kansas City, it would be so devastating to me.

RT: When I first read the piece, I could not conceive of being in a relationship in which I felt that way about someone, and certainly had never met anybody who I could imagine feeling that way about me. I have that kind of marriage now, with a man who lost his wife to cancer four years before we met, and who’d lost his beloved professional mentor to sudden illness. Even in first meeting him and hearing him describe how those losses changed him, I remember thinking specifically about the things that you had quoted Alice as saying to a young woman who had been raped, citing the King Lear line — “ripeness is all” — about how we might not have chosen such tragic and painful paths to ripeness. But sitting on the phone with this man soon after we’d begun to see each other, listening to him describe his experiences of grief, and how they’d altered him, I thought about Alice’s voice, what she had written, via you.

Do you want to show me some of the things here that make you think of her?

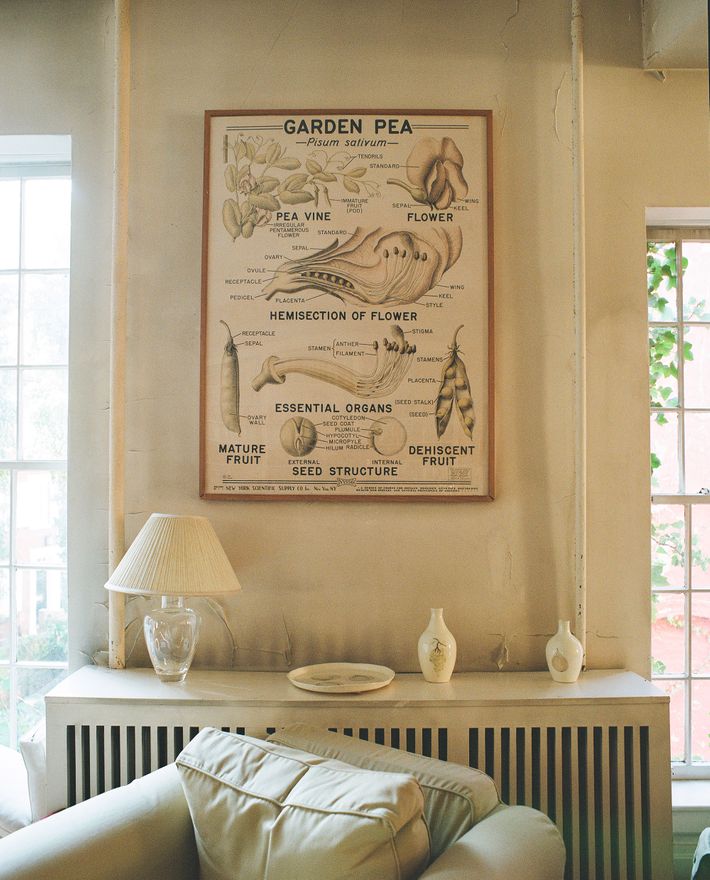

CT: [Gestures to a botanical poster of peas] Here are the Garden Peas…

RT: Where did you get that?

CT: It was around the corner on Bleecker Street, there was an antique store there for a while. I think it was before she wrote the article. She’d been thinking about it. Garden peas were sort of a symbol of getting back to your real life, your regular life.

That painting [gestures to a painting of the Flatiron building against another wall], that’s the triangle building where her parents met. Her father had an office there and her mother was in the secretarial pool. It’s by a guy named Arthur Cohen, very independent-spirited. That’s his truck . After I bought the painting he said, “Now I can get my truck fixed.” I liked that, it was direct.

RT: When did you move into this building?

CT: We moved in in 1969. We lived on one floor. There were six apartments and one floor that was open. This was under the old World War II rent-control thing, not rent stabilization, so some floors were deregulated and some floors had professionally decontrolled you could rent it at market price, people who were psychologists or something like that. One of those wouldn’t leave.

RT: What are the other things? Show me other things.

CT: That’s a painting by Jack Levine, who used to live across, have his studio across from our roof garden. Jack Levine started out as a social realist painter in the ’20s and he never changed. There’s a great quote where he says “People say, how could I reject abstract expressionism? I come from people who rejected Jesus Christ.” He was a great man.

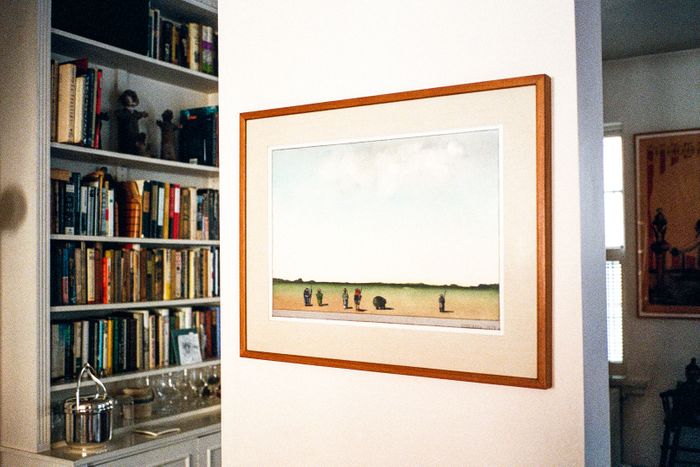

[Pointing to another painting] That’s a Saul Steinberg. She loved Steinberg. We’d gone through his studio and she stopped in front of that painting, I guess it was her 40th birthday, just after she was sick, and I called him and I said — he knew exactly what painting I was talking about … I said, “I want to buy it for her birthday.” And he said, “Oh, I meant to give it to her.” And I said “Saul, it’s not a present from you, it’s a present from me.” And he said “We’ll make a Talmudic exchange. You give me a book or something.” So we planted a tree in his yard. He used to send me pictures of it, the tree. So it was an exchange. I got the better deal, of course. Or Alice did.

RT: Is that a baby crying, by the way? Is there a baby downstairs?

CT: Yeah, I have tenants downstairs and most of them have come with one baby and moved on with a second baby. These are very brave people, they now have three babies. About 5, 4, and 6 months. I like having babies around.

RT: Let’s go up to your study. Are your daughters excited about the play? Have they seen it?

CT: They’ve heard stage readings of it. There was one at The New Yorker festival, and there was one out in San Francisco.

RT: And how many grandchildren do you have?

CT: There are four. Abigail, has two girls, and Sarah has two boys. And they’re roughly the same age. The boys are 12 and 15 and the girls 13 and 16.

RT: I’m looking at a framed advertisement for About Alice that asks the question “Does True Love Exist?” at the top. Insofar as you and Alice are being offered up as the answer to that question: Do you feel any discomfort? Do you feel like Oh no, now I’ve made it seem too perfect and devoted?

CT: No. But again, I never heard my parents raise their voice to each other, ever. Maybe there was something going on somewhere I didn’t know about, but I grew up thinking married people loved each other.

RT: Did you ever raise you voice to each other? Did you ever fight?

CT: Well we certainly had disagreements. We just cut out one in the play, where we get to Tokyo—

RT: … and she doesn’t like the room, and she wants to move.

CT: Yes. We cut it out because it just didn’t work very well. And one’s still in the play about what to pay the guy who fixed our floors. But no, as I say, I was a little surprised that people took that lesson from the book.

RT: I think it’s rare, I think it’s very rare for people. Everybody says “Marriage is hard work.” I’ve now been married for seven years and I don’t find it hard work to be married. I find it a great joy. But I don’t know too many people who have that precise experience.

CT: It’s funny, I hadn’t thought of this in a long time, but I remember thinking before I got married, a couple of friends had talked about how it was such hard work and how it was complicated and everything, but it didn’t seem that.

RT: It seemed that way to me prior to meeting the man to whom I’m married. My relationships had been very hard work. The men I’d dated, I hadn’t felt happy with them, and I think I could’ve very easily married one of those people. It happens all the time.

CT: It happens every day.

That’s Alice giving a toast at Abigail’s wedding. [Looks at photo of a boy reading his book on the can] And this, they claim, was not a posed picture.

RT: Is that one of the grandsons?

CT: Yes, that’s Natey reading one of my books over the potty. And that’s Natey’s card for his Instagram, anti-Trump cartoon. He was 15,000 followers.

RT: He has 15,000 followers for his anti-Trump cartoons?

CT: Yeah, he just turned 12 this summer. @AntiTrumpCartoons, 11-year-old cartoonist. Tell your friends to follow! Only on Instagram.

RT: I’ll follow him this afternoon. Do you follow him? Are you ever on social media?

CT: I have an Instagram thing to see his stuff. [points to a picture of a truckload of hay and an ox in a yard] That was the first night we spent in Nova Scotia. Alice got up and said “There’s a cow in the front yard.” It was Merv Clattenburg with his ox team taking the hay.

RT: Is this your Nova Scotia house? I’ve read so much about it. It’s beautiful.

CT: Alice always said it looks like the house in an alphabet book under H for house.

RT: Red-roofed, perfect, cape house from a fairy-tale. Do you still go up every year?

CT: Yeah.

RT: Can I ask you about the Richard Merkin painting [of a chicken]?

CT: Oh, yeah. I did a piece, more than one, for my sins, about the chicken that plays Tic-tac-toe in Chinatown, and one of them had this illustration. I used to take people there and they’d look at the situation and see — they’re playing against a chicken — that the chicken gets to go first. But he’s a chicken. Surely, you’re a human being you should have some advantage. And then some of them said, “The chicken plays every day, and I haven’t played in years.”

RT: This was really wonderful, thank you so much. Thank you for your time; yours has been a voice that’s been in my head since I was a child.

CT: Well, thank your father for that. I didn’t picture people reading it like that, and it’s nice.