It’s hard to think of a writer more saddled with the weight of expectation than Kristen Roupenian. Last year, her New Yorker short story “Cat Person” went viral — an extreme rarity for fiction — becoming the second most-read story on the magazine’s website that year, after Ronan Farrow’s Harvey Weinstein investigation. The story, about a sexual encounter between a woman named Margot and a man named Robert, became a cultural lightning rod. People related to the perceptiveness with which Roupenian explored the messiness of contemporary dating culture; “Cat Person,” along with a nonfiction account of an anonymous woman’s unpleasant sexual encounter with Aziz Ansari that was published around the same time, helped expand the shifting boundaries of the #MeToo conversation. As I wrote at the time, amid the glut of think pieces surrounding Roupenian’s story: “In our current #MeToo moment — when women’s messy and uncomfortable sexual experiences are increasingly taken seriously — it provides a vivid account of the sorts of ‘bad’ sexual encounters that don’t rise to the level of harassment or assault, but still merit closer examination.”

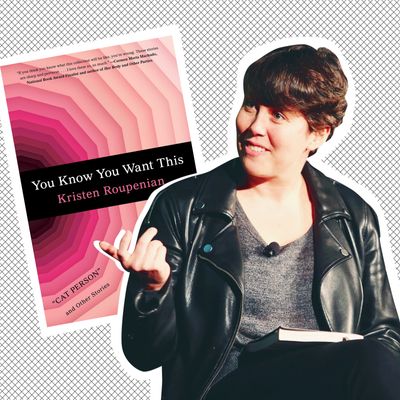

Roupenian’s first book, a short-story collection titled You Know You Want This, out January 15, proves that she has more to say. The collection of 12 short stories, titled You Know You Want This, were mostly written before “Cat Person” came out, though two new pieces were added afterward. While some of the stories, particularly “Good Guy,” the book’s longest story, about a dirtbag named Ted whose identity is wrapped up in women thinking he’s a nice guy, evoke “Cat Person” and its #MeToo-adjacent themes, others delve into fantasy and dystopia and body horror. The collection is difficult to sum up, but much of it is concerned with the power dynamics between men and women and how these play out in sexual relationships, although they often elide any simple feminist reading; The women in the book are as twisted, power hungry, and driven by desire as the men are.

We called up Roupenian, who plans next to work on an HBO adaptation of the collection as well as a new novel, to ask about the response to “Cat Person,” and the discomfort she wants readers to draw from the dark fables of You Know You Want This.

Was it difficult becoming an overnight viral sensation when “Cat Person” came out?

In some ways it’s the best thing that’s ever happened to me and it made all my dreams come true, but it was overwhelming at the time. It was hard because the #MeToo discussions are ones I care about a lot and personally feel deeply invested in, and yet at the same time, I feel in no way equipped to be a spokesperson. The idea that people wanted me to be able to speak thoughtfully about and explain why young women aren’t having the sex they want, that was a lot of pressure. With a year behind me, I feel somewhat ready to be having these conversations, but when it happened, my immediate instinct was like: I need to step back, like I’m happy that the conversations are happening, but I can’t be the voice of anything. I’m just not ready for that.

The story got wrapped up in a larger #MeToo conversation in a way that took on a life of its own, expanding the cultural conversation to be not just about nonconsensual sex but also about like the ways that sex is so often bad for women as a result of living in a patriarchy. Were you aiming to speak specifically to those ideas?

It took me by complete surprise. I was definitely not expecting it. In terms of influence, I wrote the story before the #MeToo conversation was really taking place, but I do think that the story and the movement came out of the same kind of cultural moment. I was listening to the same news, feeling beat down by the poisonous rhetoric that’s coming out of the election, hearing the Access Hollywood tape, and all of that frustration and rage and poison that I felt within the atmosphere filtered into my brain. I think the story came at the exact right moment where it could serve as a catalyst or a proxy to let people have a lot of conversations that they were dying to have but didn’t quite know how to until all these things started changing really fast.

There’s a lot of diversity in the new collection in terms of genre, some fantasy, some horror. It felt like the story about Ted, “The Good Guy,” was the most thematically akin to “Cat Person” and the most “relatable” in some ways. Can you tell me a little bit about the sort of idea behind that story and what you were hoping to explore in it?

It’s not surprising that it resembles “Cat Person” the most since it’s the one that I wrote directly after it. After “Cat Person” came out, everyone was like “Why don’t you write a ‘Cat Person’ from the perspective of the man?” and “Good Guy” isn’t exactly that, but it is closer than any of the other stories. I think that for women who read and identified with Margot when they read “Cat Person,” it’s not a super-pleasurable experience to see yourself reflected in someone who’s going through the ringer in the way that Margot does in that story. And so I felt it’s less that Robert and Ted are identical characters — I think they’re pretty different — but rather that you have access to Ted’s consciousness as he undergoes a process similar to Margot’s in that he starts out with the best of intentions and ends up in a place that is really dark and sort of hard.

The thing with these stories is that the reader is forced to identify with people who do very fucked-up things. What do you want readers to feel when they’re reading these stories?

As a reader, I love to feel uncomfortable. I like feeling disturbed. I like that feeling of “oh shit,” like catching a glimpse of yourself in the mirror and saying like, “Oh my God, is that me? How did I end up in this place? How did I end up doing that thing?” I think that these stories are written for readers who also enjoy that sensation, or are drawn to it and also who are willing to sort of uncomfortably identify with the characters. There’s a difference between a story that kind of points the finger outward and is like “this kind of person is bad or terrible” and one that gives you the consciousness of a person that maybe is terrible but is understandable enough that the discomfort is aimed inward.

There is a tendency with #MeToo stories to flatten things into “this guy’s a bad guy, this woman’s a hero” in a very reductive way. These stories show that even though people engaged in very bad behavior, there’s always nuance and complexity involved, and there are some aspects of their motivation you can relate to.

I think identification isn’t justification. It’s not an endorsement of behavior, but if you can’t understand something, you can’t change it at all. I won’t write from a POV unless I feel like I can in one way or another see at least a sliver of myself, even if it’s a part of myself that I’m really uncomfortable with. I think it’s one thing to be like “I hate Robert, Robert’s a villain,” because we don’t have access to Robert in the story, you know what I mean? He could be a villain, but we don’t know really what he’s thinking. If I’m going to write close into a brain like Ted’s from “The Good Guy,” then I have to feel some kind of empathy and identification with them because otherwise I couldn’t tell the story.

What do you think the book’s sort of overarching theme is?

I definitely do feel like there was a quote that’s kind of cliché at this point, but I really love, which is “Everything is about sex, except sex, which is about power.” And I think that is absolutely a theme of the book. I think the book is about how many of our interactions with other people are about power in a way that we don’t tend to acknowledge, and about how even when we feel powerless, we’re also trying to assert our power in one way or another. I think sexual relationships can be a really productive field for those kinds of power games.

There was also a review that just came out today — and I don’t know if it’s bad form to quote your own reviews — but the person did say something that I thought was really right, which is that the usual virtues that fiction tends to promulgate, which are the virtues of empathy and self-consciousness and self-awareness, the book spends a lot of time showing how those can be just as easily tools for exerting power and control. We have this knee-jerk adoration of empathy, but empathy is not simply a virtue; empathy involves trying to figure out what other people are thinking and responding to that, and that can actually lead you in a terrible direction. Being self-conscious or self-aware won’t necessarily lead you to act well. It could just as easily lead you to be great at justifying your bad behavior.

The book reminded me of Carmen Maria Machado’s short-story collection Her Body and Other Parties, especially the focus on diseased or damaged bodies. Why is that a preoccupation for you?

I do love Her Body and Other Parties. I read “The Husband Stitch” when it first came out and I just thought it was one of the best contemporary short stories I’ve ever read and I definitely count her as an influence. For me, part of it is that all my POV characters are sort of overthinkers who tend toward an excess of trying to interpret other people’s behavior, as I am. They’re self-conscious and self-aware, often to their detriment and the detriment of those around them. I think that maybe one small piece of the body stuff is that people like that tend to sometimes forget they are in a body and are vulnerable to a body. Not to sound like an old person about it, but as communication becomes more and more electronic, the more you become and abstracted kind of “intellectual” person, the more the return to the body can become a sudden and unexpected and painful surprise.

Most of the relationships in your book explore the dynamic between men and women. Is there a reason that you focused on that and do you plan to write more queer characters?

The practical reason is that although I am queer and I’m in a relationship with a woman now, for a very long time, I was in a long-term relationship with a man, we were engaged, and I feel like a lot of the stories that came out of this book came out of a very particular time in my life. I often say to people, I feel like there’s a five-to-ten-year lag between when something happens to me and when it starts appearing in my fiction, so Lord knows what will happen in the future. From a thematic perspective, a lot of the stories are about sex and are also about the power dynamics between men and women in a patriarchy. Even if you’re queer, you live under patriarchy and are subject to understanding who you are as a woman in a world run by men, and I think that that power dynamic is the central focus in a way that brings men very regularly into the stories and become stories about women trying to assert their power over men or escape the power that men are trying to exert over them.

Where did the idea for the title come from?

It was originally a line in one of the stories. But it came to mind when I realized that it could fit as a line in almost every story if I wanted. And it’s because so many of the stories are about conflicted desire and about one person trying to force or coerce another person to want something that they don’t want.

Lately there’s so much good writing told from women’s vantage points, featuring these sort of flawed and complicated and unsympathetic female characters. Does it feel like an exciting moment in fiction to you? For sure. I love it. I love a messy kind of violent angry female protagonist more than just about anything else. And I do think that when I was a teenager I mostly read male writers who would occasionally have those like protagonists in them but the books themselves aren’t written by women. And now there does seem to be a newish hunger for that kind of writing and an enthusiasm on the part of both readers and writers to see how far they can go and to push the boundaries of where women readers in particular are willing to go, and how dark so many people are willing to go in terms of their reading habits. So I feel delighted because I was like that my whole life, but I didn’t know that anybody else was like that.