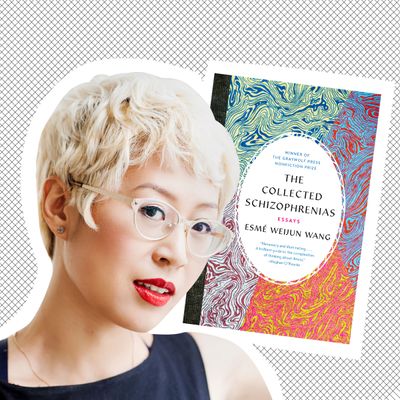

In her Graywolf Nonfiction Prize–winning essay collection The Collected Schizophrenias (out February 5 from Graywolf), Esmé Weijun Wang combines research and reporting with personal storytelling to examine some of the biggest questions and challenges in the way society views, treats, and talks about mental illness — specifically the widely misunderstood and misrepresented category known as the schizophrenias. Wang was originally diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and later with schizoaffective disorder. In The Collected Schizophrenias, she describes the convoluted and frustrating path that led to this final diagnosis, which was later complicated with an additional diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease.

In one essay, she describes how she was essentially kicked out of college when her psychosis started acting up, and tackles questions about how mental illness is treated on campuses. In another, she describes her experience with involuntary commitment, and interviews people on both sides of the heated debate about whether involuntary mental-health care helps or hurts those who are suffering. And in another, she questions the line between mental illness and prophetic visions, and whether there’s a spiritual element to what she’s experiencing.

Wang spoke with the Cut about her new book, unanswerable questions, and navigating the challenges she writes about.

What do you see as the biggest, most common misconception or misrepresentation of the schizophrenias?

I think it’s mostly confusions about what schizophrenias even are. The idea of a split personality is really common. Or the idea of psychotic behavior, or psychosis being a very general idea of what craziness is, this very random, incoherent behavior akin to someone screaming on a bus, or acting very violently and without cohesion or coherence. I think that’s where most people’s understandings of schizophrenias begins. So, that’s where I think I’d start in terms of people’s misunderstandings.

In order to gain a more accurate picture, I’d start with talking about what hallucinations and delusions are. I’d talk about the idea of hallucinations being false sensory perceptions — so, seeing things that aren’t really there, smelling things that aren’t really there, hearing things that aren’t really there such as voices, and delusions are believing things that aren’t true such as the FBI is out to get you, things like that. And I’d direct them to the DSM-5 for the definition of schizophrenia or the schizophrenias, as I call them, which also encompasses schizotypal disorder or schizoaffective disorder, which is what I have — as well as other schizo-related disorders. I would start with those terms to get the general idea.

Do you think it’s harmful to people struggling with these disorders when people casually use words like “crazy” or “psychotic”?

I think so, because they are used in negative ways. No one uses “psychotic” or “crazy” in a positive way. There are people who are trying to reclaim those words, as many marginalized communities tend to use colloquialisms that are negative in a way that is reclaimed: people of different racial and ethnic communities, or queer communities, et cetera. But, in general, I would try not to use those words if one is not part of those communities.

One of the most interesting things about this book is the way you weave research into your personal story, so I wanted to ask a little about that process. Was there anything you discovered during your research that really surprised you?

Yeah, definitely. Looking more deeply into different aspects of the schizophrenias, or into aspects of mental health issues, just gave me a second look into things that I thought I knew. One thing was the movie A Beautiful Mind, about John Nash, the Nobel Prize–winning mathematician who had schizophrenia. When I took an abnormal psychology class as an undergraduate at Yale University, there were a number of movies we watched in order to discuss how incorrectly Hollywood portrays mental illness, and one of those examples was A Beautiful Mind. And, what we talked about with A Beautiful Mind is that it portrays schizophrenia as similar to having imaginary friends. One big surprise in the movie is that you learn that his best friend in the movie turns out to be imaginary, and that’s supposed to be a symptom of his psychosis. You learn that partway through the movie, and it’s this big kind of M. Night Shyamalan-esque twist. And so something we discussed in that class was, like, “Oh, what a ridiculous way of depicting schizophrenia. That’s not how delusions work.”

It wasn’t until I went back and was reexamining the movie that I realized that it was actually a pretty clever way of talking about schizophrenia and psychosis, particularly delusions, because it’s very difficult to portray delusions or false beliefs to an audience watching a movie unless you kind of pull them into the false belief. And the way to pull the audience member into the false belief is to, for example, have them believe that John Nash in the movie is really being given a secret mission from the CIA and that’s why he’s having these secret meetings that are fake in the movie. That was an example of something that I took another look at once I was thinking again about the way Hollywood portrays mental illness.

You also write about various things that can negatively impact your mental health, or threaten your grip on reality. How was it to spend so much time researching and writing about this topic, did it impact your mental health? Was that something you were prepared for or worried about?

In some ways, I was very prepared, and in other ways I was very not prepared. I thought it would be much easier for me because I wasn’t writing a straight memoir. I had many friends who had written memoirs, and I had seen them have a very difficult time reliving their experiences, and I thought to myself, “Okay, well I’m going to kind of escape that experience because I’m doing something different, and I’m doing something that isn’t so much about re-creating my personal experience.” But it was just as perilous as writing a memoir, because I would have to dip into the unreality of the psychosis that I was writing about.

So, for example, when I was writing the essay about the Slenderman story, about the two girls in Waukesha who tried to kill their friend, I ended up researching the story of the Slenderman, and I became very concerned that I would lose my sense of reality and would start to believe in the Slenderman myself. So, I had to take all kinds of precautions in doing that research. I had to watch the HBO Slenderman documentary with my best friend. I had to make sure that I did certain things during the day when I had more stability. I had to make sure that I was taking care of myself, that I wasn’t forgetting to take my medications.

And, in writing other cases that did dig into more traumatic aspects of my life, when I had to read hundreds of pages of my journals, that I also had to do a lot of self-care. When I did end up having a lot of nightmares, for example, because of reliving that trauma, I had to make sure I had people I could reach out to, or talk to my therapist, and not lose myself in the reality of the trauma of the reality of my past.

In addition to writing you provide a lot of guidance and resources to people working with various limitations on how to take care of themselves and balance productivity with patience and compassion for themselves. Can you say a little bit about that aspect of your work?

Yeah, I started building those resources around 2014 when I started making this website, which is now called “The Unexpected Shape.” The unexpected shape is the unexpected shape of our lives — the boundaries that we were not expecting to live with, but that we end up having to live with. I like to say that they’re often resources that I, myself, would have liked to have had three to four years prior to whenever I make them.

One example is the free encouragement notes, which is this free series of emails called “Encouragement Notes” that you can sign up for, and they just pop into your inbox and drop a little bit of encouragement every day for a number of weeks. There’s also this paid series of lessons as part of an online course. There are video lessons and written lessons about restorative journaling through difficult times, and that’s through my own development of teaching myself how to journal in a more productive and restorative way as a way to help myself through tough times over the last two decades or so. Right now, I’m working on a longer online course that builds off of a workshop that I taught live at conferences called “Ass-Kicking With Limitations.” So, creating those resources is something that I like to do while I’m not writing.

So when you talk about limitations, I know you’re also living with Lyme disease in addition to mental illness. How do you feel those things interacting in your life?

The last five to seven years of my life have been so interesting. I first thought that my mental health issues were so clear-cut. Then I started having very serious physical challenges with no clear diagnosis. They thought I might have anything from cancer to all sort of autoimmune issues, before I was eventually diagnosed with Lyme disease. With the diagnosis of Lyme disease came a sharp drop in the symptoms of schizoaffective disorder, so that was confusing.

My symptoms of late-stage Lyme have improved significantly in the last few years, then a month or two ago I had a quite sharp increase in psychotic symptoms that I wasn’t expecting at all, and my psychiatrist and I couldn’t explain it. I just describe all of this to say that I find it all quite baffling. I really don’t know why any of this happens the way it does. I don’t know the answers. I’ve had people tell me that my mental issues are because of Lyme affecting my brain. I’ve had people tell me the Lyme stuff is all because of psychiatric stuff. At this point, I’m not willing to discard anything, honestly.

I think that’s why the end of the book ends where it does, which is with a lot of questions — a lot more questions than the beginning of the book even starts with, and the beginning of the book starts with quite a few questions. I think the more I look into the depths, the more I realize that I don’t know.