John, 61

Prison psychiatrist

Los Osos, California

I moved to California from Texas at the behest of my wife, who pretty much said, “I’ve had it — I wanna move to California.” I’d planned to set up a private practice when I got here. It’s a lot more varied and a lot more gratifying. But it also tends to be all-consuming.

I needed some cash flow, and I started working at a men’s prison. I found that it was a lot easier: I didn’t have any overhead. I wasn’t on call every night. I had paid vacations. I found myself sleeping better. My mother and my wife — the two people who know me best — said, “We can’t believe how much more relaxed and easy you are to be around!”

When you work at a prison, you have to go through a lot of security checkpoints. It takes me a good 20 minutes to get to my office. There are guard towers everywhere, and they have people who have guns. The compound is surrounded by two 20-foot chain-link fences with coiled razor wire on the top. In between the two fences are electric wires, to make it so nobody’s getting out of there.

Before I go to my office, I pick up — they call ‘em “pads.” It’s like a garage-door-opener that is specific to my office. If an inmate is trying to assault me or I feel unsafe, I hit it and I’ll get something like 15 custody officers there within moments. I’ve probably used it once or twice in 20 years. More often than not, you have false alarms. I’ve done that maybe three or four times, where you accidentally sit on it or hit it inadvertently, and then all the custody officers run. You have to buy them doughnuts the next day to get them to forgive you.

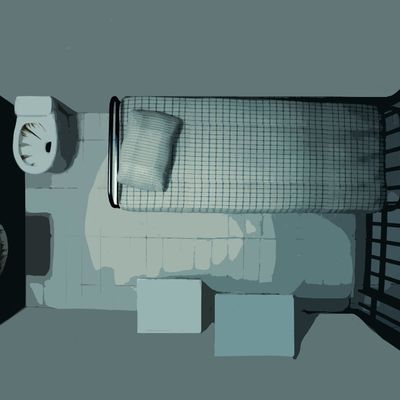

I see about 8 to 12 inmates a day. They come to my office about every half hour to 45 minutes. There’s a custody officer right in front of the clinic and he’ll say on the PA, “Joe Smith, report to C quad Psych Services at this time.” The officer pats them down to make sure they don’t have any weapons, and I usually meet them at the door and walk them into the office. Almost 80 percent of the time it’s fairly friendly. You know: “How are you doing today, Mr. Smith? Come on in — shut the door as you’re coming in.” Then I just begin the interview.

Most of the patients I see have been there for some time, and I know them. About four times a week, we’ll see somebody new or new problems arise. Maybe 25 percent of the people we see will feign mental illness to keep from being transferred out of state. California’s overburdened, so they try to send them out to Arizona or Mississippi and so forth. Nobody wants to do that. They’re not allowed to send mentally ill patients out of state. Or they’re gang members and wanna do some free time, some easy time, and not be around dangerous situations.

Many are willing to go to great lengths to stay in the mental-health program. They’ve been known to scratch their wrists. They don’t cut it very deep but — you know. They’ll say they have chronic pain; they’ll claim depression, or say that they are having auditory hallucinations. They’ll tell us that little green men come to their cells at night and talk to them. They’ll be telling me, “I hear voices — I wanna be on medicines.”

A lot of inmates, they’re sullen and angry and, “Ahh, you don’t care — you’re just like all the rest of the doctors around here. You’re just part of the system. You’re just as bad as the cops.” You ask them, “What’s bothering you? Can you tell me a little bit about that?” “I said I’m depressed! You’re the doctor! Why don’t you just give me something?” They’ll get very angry if you don’t give them the exact kind of medicine they want — and sometimes the medicine they want is either inappropriate or addictive.

Some of the inmates are what we call antisocial. This is kind of what the public would think of as a criminal. I saw a young man the other day: He has very little guilt or remorse, and he’s proud of how tough he is and how people don’t want to mess with him. He says that he wants to work on his anger issues. But really, a lot of these guys, what they’re really struggling with is dealing with the consequences of their impulsive behavior. They don’t have any trouble with emotional problems until they get caught.

But I’m hesitant to write anybody off. I’d rather be swept up in their lie than be cynical and miss something. If you’re gonna make a mistake, you want to err on the side of caution. That being said, if I ask the cell-block custody officer if he has any observations about a patient’s behavior and he says, “Oh, yeah, he’s having fun on the yard — he’s out there talking with his homies,” that doesn’t dovetail very well with him telling us how depressed he is.

We spend a lot of time helping inmates modulate their feelings, talking about appropriate ways to deal with anger. They just fly into a rage — yelling profanity, or, in the worst circumstances, hitting somebody. We’re talking basics: impulse control. Learning how to delay gratification. Things you would’ve hopefully learned as a kid. Like, “I can be angry and not hit you.”

The patients that I’m most able to be helpful with are ones struggling with depression, anxiety, or psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Of my total caseload, I’d say that that makes up maybe 10 to 25 percent. People who are profoundly depressed, who feel wretched about letting their family down. Often, they’ve had drug or alcohol problems, and once they get off the drugs, there’s a great deal of remorse. Those are the people we can make a difference with, both with medications and brief psychotherapy and counseling. The number of head injuries we see is truly astounding. I mean, it’s gunshot wounds to the head, beaten with a bat, unconscious for days.

There’s nobody that is not gonna be worse as a result of being in prison. If you already have difficulties, it’s only gonna make that worse. They’re having trouble coping and dealing with the rules and being away from their families and not having anybody they can really open up to.

There was an inmate who suicided — successfully. He’d killed his wife after he caught her cheating on him. After twenty years, he realized how horrible that was, and how he had no right to do that. He never forgave himself for it. If you’re a cardiologist, you’re gonna lose some patients to heart attacks. And if you’re a psychiatrist, sooner or later, someone’s gonna kill themselves.

When inmates have a long time in prison — the inmates have actually taught me this — there are four things they do to survive. You’ve gotta exercise regularly. You’ve gotta keep growing mentally: reading, learning a new language. It’s helpful to develop some sort of spiritual program, to try and figure out, “Why have I gotten here, what is my life, how can I have meaning?” The final thing is: who are you hanging out with? There are cliques — they call it “politics” — where blacks gotta be with blacks, whites gotta be with whites, and, you know, you can’t be talking to so-and-so and that kind of stuff, otherwise people get beat up or stabbed.

This is even true for staff members. It’s an oppressive place, and there’s a lot of negativity. How do you keep your outlook positive and hopeful, yet realistic? I kind of do all those things I mentioned that the inmates do. I try and be realistic. I try and help each person as much as I can, and if I see that this is not a person amenable to any help, I try to at least not alienate them.

One of the questions I ask in interviews is, “Do you feel like there’s anyone in your life who you feel sure loves you?” To laypeople that seems like a foolish question, but many of these inmates will look at you like you’re foolish for even thinking that love exists. Maybe one in five had an intact family. Many grew up in foster homes. A patient with a good prognosis is more likely to have a family who loves him, people who care about him, and he feels bad about letting them down, so he’s got a lot of motivation: “I wanna get it right this time.”