|

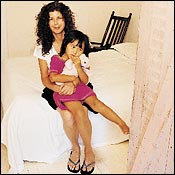

| Marie in her West Village apartment with

Inan. (Photo Credit: Joseph Maida) |

About ten years ago, I moved

into a railroad apartment in the West Village: five flights

up to a long, narrow space that my sisters, who live in houses,

might call a hall. When the apartment was swept and uncluttered,

tulips standing on the table, it looked like a sliver of a

country house. As long as you didn’t move. This place

is so peaceful, friends would say, so serene—and it

was, unless the neighbors were home. I nodded on the stairs,

but I had no desire to know the people across from me: two

adults and one young daughter living in a space too small

for even one person. I’d come to New York to escape

the white affluent suburbs, to live with different kinds of

people, but this was just too close. Their language, their

cooking, their shouting: Everything they did seemed foreign

and loud. I closed the door; they came through the wall. The

man’s snoring woke me. “Stephanie!” I heard

the mother call to her daughter so many times it was a song

stuck in my head. When the family’s friends came over,

their conversation and laughter drove me from my desk, forced

me to walk the streets. Then the worst thing happened.

They had another baby. And that child cried for twelve to

sixteen hours, day and night. I banged on the door. I called

the landlord. Who were these people? Why wouldn’t they

move? At that time, I was trying to conceive a child with

the man I loved. Inches from my neighbor’s snoring we

would be having the industrious sex people who are paying

for rounds of fertility drugs have—and then the baby

would start crying. And crying. Come on, honey, he’d

say, we have a job to do. But by then I’d be sobbing,

too, curled up in a fetal position under the sheets, my hands

over my ears as the baby screamed.

We broke up, and I was single again. As the baby next door

grew into a toddler (“Sabrina!” the mother endlessly

called), I began the long process of adopting a child from

China. Finally, I received the photograph of my future daughter,

a sturdy, sad-looking 3-year-old girl named Yi-Nan, and it

was time to go.

Three weeks in three Chinese cities (bicycles, smog, scorpions,

SARS, an appendicitis attack), Yi-Nan sobbing throughout the

fifteen-hour flight, and we were back in New York, slumped

in a cab speeding through the rainy night. As I lugged my

new daughter up my building’s five flights of stairs,

I began to hear voices, and then I saw them: Stephanie and

Sabrina; their mother, Maria; and their father, the snoring

man, Carlos. Everyone had crowded into the stairwell to greet

the little girl who pressed against my shoulder. It wasn’t

until the next morning that I saw the blown-up color photographs

of Yi-Nan—I had no idea who had gotten them or how—pasted

on the walls and doors with WELCOME HOME crayoned beneath

them.

I hardly noticed, in the blur of those first weeks, how

the presence of my next-door neighbors began to comfort me.

Maria and Stephanie would coax Yi-Nan (whose name had morphed

into Inan) up the stairs as I staggered behind. Then gifts

began to appear: a child’s baseball hat hanging from

the doorknob, two or three laundered dresses neatly folded,

a large Tupperware container of plastic action figures.

I was a 52-year-old working woman, living alone with a disoriented

3-year-old who spoke only Mandarin. I was barely coping. Although

my friends cheered me on, they didn’t live with me;

my neighbors did. One day, Stephanie stood in my doorway as

I put away groceries. Another day, both Stephanie and Sabrina

came in. Soon they were stopping in regularly to teach Inan

numbers and letters and who Barbie is. When I struggled to

get my stomping, crying daughter dressed, they materialized

snapping their fingers and singing “You can do it”

as they danced around. They charmed her, they calmed her;

they made her laugh and learn English. And they taught me

how to teach her, they taught me to have fun.

Not only our next-door neighbors but the whole building

rallied to my support. Our landlords threw a baby shower.

Will and Peter, who lived below us, carried up groceries and

very often Inan as well. Soon doors were opening each morning

like little windows in an Advent calendar as our neighbors

called out “good morning” to the little girl counting

“one, two, three” as she walked downstairs.

I don’t remember when Maria and I began keeping the

doors between our apartments open. I crossed into her kitchen

one evening to see Inan sitting with the kids and eating spaghetti.

“It’s okay?” Maria said. “Yes,”

I said, “if it’s okay with you.” Inan looked

up, smiling, her mouth smeared with sauce.

When I was sick, Maria took Inan next door and fed her.

When Inan was sick, Will took time off from work to babysit.

And when Inan’s fever reached 105, Maria showed me how

to wrap her in cold towels. Back from the doctor, we found

coloring books waiting for her.

Our doors were open almost all the time now. The children

ran back and forth, and Maria and I walked into each other’s

homes with only a knock on the woodwork. Stephanie and Sabrina

and Inan decorated the little Christmas tree we’d carted

home in the stroller (Peter carried it up). And on Christmas

Day, when Inan had been in New York nine months, and a group

of us were opening presents, Will and Peter brought us a Christmas

breakfast of eggs and ham and blueberry muffins. It was the

happiest Christmas of my life.

Children bring blessings, an old friend, a mother, once

told me: Children open doors. Inan and I had come all the

way from China to find the people who would make our new life

possible: our generous neighbors, who had been there all along.

Marie Howe teaches at Sarah Lawrence College and is the

author of What the Living Do, a book of poems.

|