Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist and critic Art Spiegelman has spent more than 30 years digging through the past to recover and highlight vital stories that might otherwise be forgotten. Spiegelman first gained fame for Maus, a graphic memoir about his father’s experiences as a Polish Jew living through the Holocaust — and about his own experience of struggling to understand and relate to his father along the way. More recently, he’s devoted himself to honoring underappreciated graphic novels, specifically whole narratives told only through images.

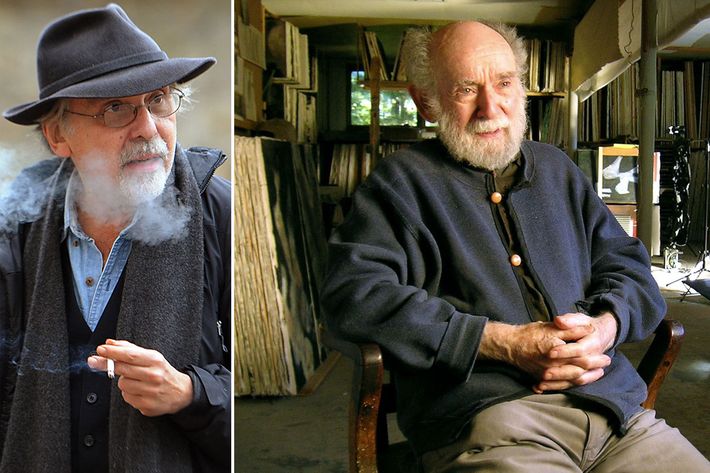

While researching a 1930s style of graphic novel, Spiegelman stumbled on the work of Si Lewen. A Polish-born Jewish-American like Spiegelman’s parents, Lewen created evocative and eclectic works of art throughout the latter half of the 20th century, and garnered praise from Albert Einstein, but eventually faded into obscurity. When Spiegelman tracked him down, he found a nonagenarian who was still making art, even in his rest home.

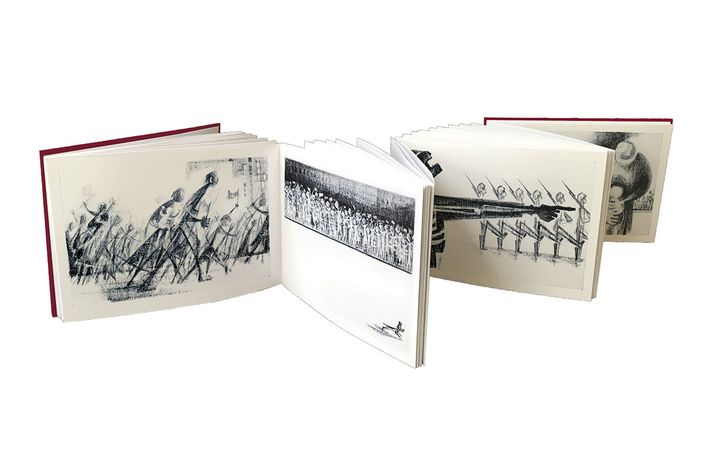

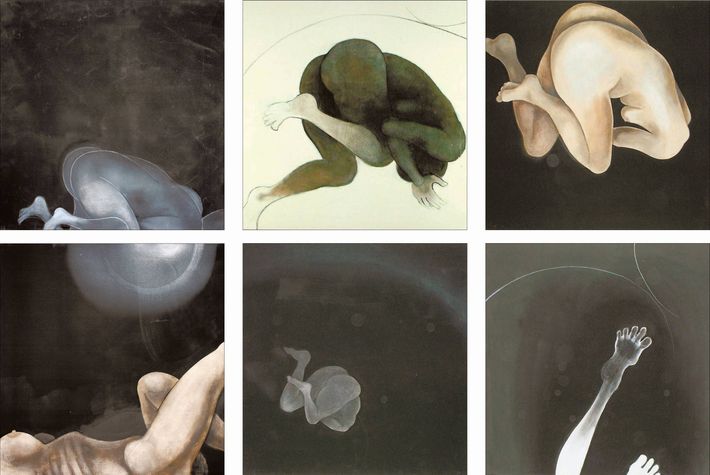

The pair became friends, and Spiegelman suggested they publish a book of Lewen’s work. Ten days before Lewen died, this July, at the age of 97, Spiegelman presented the painter with an early proof of Si Lewen’s Parade: An Artist’s Odyssey. The book, presented accordion-style, features about 60 black-and-white drawings that explore the recurring drumbeat of war, and Lewen’s 90 years of experience with its devastation.

We caught up with Spiegelman to talk about why he and Lewen chose that format, Spiegelman’s attempts to educate the art world about Lewen, and why comics art pierces your consciousness more than other mediums.

How did you and Mr. Lewen become friends?

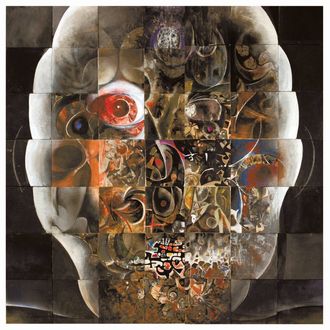

I had gotten interested in the genre that is the precursor to the first graphic novels, that flourished between 1918 and 1938. I stumbled across a reference to a guy named Si Lewen and I looked up what he did, and I said, this is mind-blowing. It’s a little bit later than the others, it’s after World War II, and it’s probably the most evocative and moving and richly visualized of all of these things. And then I got to find out his backstory. He was a very successful artist after World War II, he turned his back on the art world because people kept telling him what to draw and that wasn’t his thing. He was interested in exploring himself and the world through painting. Instead of being a bullshit artist and hanging out with the potential buyers he moved away from the city and just got more interesting and more prolific as the world went on.

How did the book project come about?

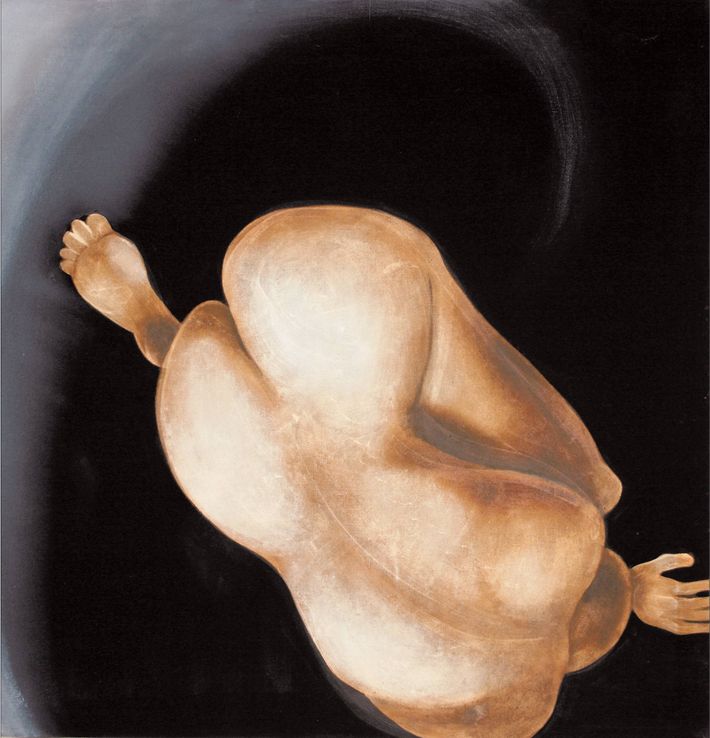

As we got to know each other, I realized this book should available. As Einstein said, [in a letter to Lewen], “our time needs you, and your work,” and it seemed just as true to me. He was born around Armistice Day during World War I and he and his family moved to Germany where they would be in safer quarters in Berlin. They were living in a circle of artists, writers, and intellectuals, and Si was popping around these museums in Berlin, and he would come home and say, “I talked with the paintings. The only thing that is so sad is they should be closer together so they can talk to each other when I am not here.” And that is the key to what became the most interesting part of his very varied career as a painter — paintings that talked to each other. He ended up making a long series of paintings. He wanted to make a hundred feet of paintings called the Centipede. And [he] would keep these projects and nurse them for long periods of time. All of this makes it relevant now. This idea of a painter’s work being an instillation, as well as whatever is on the canvas, is something I have been seeing more and more of. But it wasn’t part of the repertoire when he was coming up through the entire history of modernism.

What was his reaction like when he first saw the galley of the book?

He wouldn’t let it go. He would lift it up, turn it around, and say, “I’d like to see both sides.” At the same time, he was kind of marveling at it. He didn’t understand how this thing could be. It seemed to make him very, very happy. We brought him some wine, and we had a little Dixie Cup toast to the book. He was petting it, and he would unfold it, fold it, and he was just deeply moved.

What do you think that moment meant to him?

Well, I think that is why this path led to my telephone call here. He felt a kind of vindication. Not with an “I told you so,” but a vindication that he did have this whole life, and his paintings were really important. He didn’t have to argue with anybody about that, and it wasn’t the reason he was painting.

Do you remember a moment when you felt like that yourself, when you felt like you were receiving recognition for your work?

Well, yes, in a sense. I knew what I was doing was important and it was different from what other people were doing. I admired what other people were doing. It didn’t come with a superiority complex, I just assumed if people didn’t know of my work, it was their fault. So this was before Maus. Even back in the underground-comics phase. I guess it is the responsive cord I found in Si. When I was making Maus, which took about 13 years, I expected it would have a small cult audience and we would publish it ourselves. And I thought it would be found posthumously, like, ‘Oh wow, that was a really interesting thing someone did back in the ‘80s.’ And much to my surprise, I found out that I was only minutes ahead of my time rather than decades.

Do you think there is a randomness to who gets vindication or validation in their lifetime, or is there some logic to it?

Well, you can never predict the logic, because needs change. Vermeer wasn’t recognized for hundreds of years after his death, and now I would say he is wearing some kind of crown. I see some people whose work is really great, and some people get the tip of the hat that comes with that. But it is obvious to me, at least, that they are equal in their greatness. Then there is the factor that this is going to get lost in the fire. How is anyone ever going to know what happened here?

And it seems that part of this project is making sure that Mr. Lewen’s work isn’t lost in the fire.

Exactly, and that is why I say the vindication was him seeing the book. By the time that he saw this strange but appropriate object in front of him, basically this was more central to his life than any tombstone might be, as a way of being seen.

There is a rumor one of his pieces is getting purchased by a major art museum.

Anything at this point is name-dropping, because I don’t know what ones will turn into hot air and what ones will be real, but it seems like there is enough interest within the first month the book has come out that someone will say they are interested. I just got a letter from a museum in Paris that is interested. But I can’t tell. I can just honor the commitment I made to him. It would be good for him.

You said that he passed away ten days after seeing the book. Do you think that was a coincidence?

Even his daughter said, this [book] gave him permission. She said he hung on to see this book. I talked to a couple of people hoping they would get an obituary done for him. Eventually a letter came back from someone at the Times, that said, ‘It seems to us that Si Lewen didn’t centrally affect 20th-century art, so his only claim to fame is that Art Spiegelman is interested in his work.’ But if I had been able to talk back, I would have said the reason I am interested in his work is because he is central to 21st-century art, the idea of making paintings that talk to each other, pictures returning to a narrative function after Expressionist art and Duchampian gestures I see echoed in younger painters. These were people making pictures bigger than the edge of the canvas.

So he didn’t end up getting the Times obituary?

No, it didn’t happen. But I think they’ll regret it. They’ll go, ‘Oh shit, we blew it.’