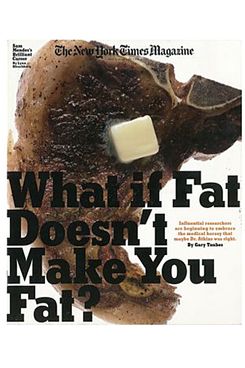

In July 2002, The New York Times Magazine published “What If It’s All Been a Big Fat Lie?,” a cover story by food journalist Gary Taubes arguing that the carbohydrates in our diets, not the fat, were the likely cause of obesity and heart disease. What sounds perfectly reasonable now — essentially a defense of Atkins and Paleo — was at the time akin to heresy. The critical avalanche that followed was swift and relentless, including a Center for Science in the Public Interest newsletter cover accusing Taubes of promulgating “Big Fat Lies,” a Reason magazine takedown headlined, “Big Fat Fake,” and a Newsweek scolding, written by a former friend, titled, “It’s Not the Carbs, Stupid.”

Almost fifteen years later, much of what Taubes was pilloried for writing in 2002 has become conventional wisdom. Michael Pollan has since referred to Taubes as the Alexander Solzhenitsyn of nutrition research, and he’s been asked to lecture at over 60 universities and medical schools worldwide — from the Mayo Clinic and the Cleveland Clinic to Harvard Law School and Oxford University. Taubes is now widely considered to be one of the most influential authorities in nutrition. With his latest book, The Case Against Sugar, coming out from Knopf in December, we asked him to write about his time in the wilderness. Below, in his own words, Taubes ruminates on bouncing back from professional ridicule.

Here are three issues I have with the concept of vindication, at least of the variety for which I am, regrettably, a candidate.

1. You have to establish the conditions for vindication to be necessary, which means you first have to be publicly shamed or ridiculed, an experience I personally could have lived without.

2. Vindication is not a binary phenomenon; it’s not a yes or no, black or white thing. The people who had publicly insisted you were an idiot are very likely to continue to do so, rather than admit or, perhaps more important, acknowledge to themselves that they might have been wrong. That’s human nature. The best you’ll ever get is some degree of vindication. Never the whole thing.

3. The orthodoxy can always protect itself by accepting your once-heretical ideas as valid, but conveniently forgetting or ignoring the heretic’s role — i.e., yours — in forcing the issue. This is the “we knew it all along” scenario. It wouldn’t be a cliché, if it weren’t so likely to play out. Any heretic should find such an outcome sufficient, but it’s only natural to want credit for one’s contributions, particularly so if they’ve been accompanied by public shaming and credibility is required for you to make a living.

My particular heresy was to author an article in July 2002 that the editors of The New York Times Magazine thought sufficiently controversial to feature on the cover with a memorable if not infamous photo of a porterhouse steak and a pat of butter. The headline was guaranteed to incite the orthodoxy, if not implicitly insult them — “What If It’s All Been a Big Fat Lie?” The article argued that the conventional thinking on nutrition that we’d been living with since the 1970s was likely to be incorrect, that we should be avoiding refined carbohydrates and sugars, not eating low-fat diets, and that maybe it was the infamous Dr. Robert Atkins, of all people, whose advice we should be taking, at least if we are fatter than we prefer, as an ever-increasing number of Americans surely are. To suggest as I did in the very first paragraph that maybe Atkins had been right all along was a surefire method to bring the article maximal publicity, induce the greatest backlash and, whether my editors knew it or not, maximize the book advance that would assuredly follow.

The advance paid for the next four years of my life and so the research and writing of a book, Good Calories, Bad Calories, that (regrettably) would take five years. First, though, I would be publicly shamed. I had expected the article to be controversial; I had no idea quite how much. A 2012 article in the Columbia Journalism Review described the reaction as “a sustained, near-operatic chorus of censure.”

In retrospect, my article had aggrieved two significant constituencies, not just one. By proposing that the nutrition authorities had made inexcusable errors, I had implied that my journalistic colleagues who covered this field had also botched the story, if not missed it entirely. We all like to think we’re good at our jobs. If I was right, they weren’t. Not on this subject. Hence, I couldn’t be right. More human nature.

The Washington Post published a lengthy exposé by a reporter who had spent decades faithfully reporting what the nutrition authorities told her. She claimed that my “key assertions were contradicted by a significant amount of high-quality research,” although my greatest sin, the Post article implied, was that I had confused the public. Better that every authority and journalist agrees on the wrong answer, by this logic, than that one or a few of them actually be right. Reason magazine published a lengthy exposé calling me (or at least my work) a “Big Fat Fake,” authored by a reporter who had written a book faithfully reporting what the experts had told him. The Center for Science in the Public Interest, which had been faithfully promoting low-fat diets since the 1970s, published a lengthy exposé accusing me of committing “Big Fat Lies” and Newsweek published a shorter exposé, “It’s Not the Carbs, Stupid,” authored by a friend who had recently published her own book on obesity and had more or less faithfully reported what the experts believed. My friend had considered me one of the best and most astute science journalists in the country, but that changed once I came to different conclusions than she had. Now she accused me of selling out to procure a large book advance. That would be a common accusation.

Since then, I have clearly moved toward vindication. Aspects of my once-heretical arguments have become orthodoxy. Michael Pollan has described me as playing the Alexander Solzhenitsyn role in nutrition for my investigative reporting on the scientific bankruptcy of the low-fat nutritional wisdom. Even the U.S. Department of Agriculture and its dietary guidelines now suggest that the first principle of a healthy diet is not the reduction in fat, as it was from the 1970s through 2002, but in processed and grains and sugar. That has reached “we knew it all along” status. Time, which launched the official institutionalization of the low-fat-is-good-health dogma with a memorable cover article in 1984 (“Cholesterol: The Bad News”) reversed itself with a 2014 cover story ( “Butter Is Back”). Even Jane Brody, the iconic New York Times personal health reporter, who led the journalistic charge for the low-fat diet in the 1970s and 1980s, recently conceded that maybe butter and saturated fats were no worse than the pasta and bread she had suggested in her own best-selling books to be consumed in quantity. I thought I’d never see the day.

While the orthodoxy has yet to embrace Atkins and low-carb, high-fat diets, or ketogenic diets as they’re technically called, as healthful diets, let alone ideal, they’re getting there. Hundreds if not thousands of physicians now preferentially prescribe them to their patients, and the bookstores are overflowing with diet books and cookbooks, promoting variations on these themes. There’s even a yearly international meeting of academic researchers and physicians just to discuss what they consider the somewhat remarkable clinical efficacy of ketogenic diets in treating an ever-increasing spectrum of rare to common disorders. The world has certainly changed. We are making progress.

So have I personally been vindicated? I wouldn’t go that far. Yes, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation awarded me a prestigious three-year grant to follow up my book Good Calories, Bad Calories with one specifically on sugar — The Case Against Sugar, which is coming out shortly. The reviewers so far seem to love it. And I co-founded a not-for-profit organization, the Nutrition Science Initiative (NuSI.org), which has had some rocky times lately, but also raised some $30 million to fund research at Harvard, Stanford, the NIH and elsewhere, targeted at resolving the controversies I’ve done my best to inflame.

But vindication is clearly in the eyes of the beholder. In the course of the research for Good Calories, Bad Calories, I concluded that one bedrock assumption about obesity, held widely by everyone, and even by me when I wrote my infamous 2002 article — “excess calories, after all, are what causes us to gain weight” — is indeed not only wrong, but almost incomprehensibly naïve, if not meaningless. As such, I’ve been arguing since 2007 that to insist that obesity is caused by consuming too many calories is as inane as it would be to say that poverty, for instance, is caused by earning too little money. It confuses a description with an explanation and is another profoundly inexcusable error. This goes after the fundamental paradigm of our understanding of obesity and so the most critical health issues of our time. And it implies that the research community has committed an error in judgment and consequences of a magnitude that may have no precedent.

Does the relevant medical-research community and the journalists who cover it think I’m right? In other words, would those who bought into the orthodoxy, circa 2002, now agree that I’ve been vindicated? Not even close. That thinking might have been captured best by a recent Amazon review of Good Calories, Bad Calories: “Another bad book written by an uneducated reporter! Zero stars! wrong wrong wrong! THIS IS WHY UNQUALIFIED, UNEDUCATED PEOPLE SHOULD NOT BE WRITING ABOUT NUTRITION!” Clearly, vindication is relative.