The version of history that goes down as conventional wisdom rarely reflects the complexity of what actually happened. As the years pass, the newspapers condense the narrative into digestible shorthand. The winners get to keep repeating their version on television and in books, while the losers have no forum. Our memories play tricks on us. The recent, lived past is a palimpsest—the older memories remain partly visible but are obscured and changed by fresher ones.

So, when we think of Rudy Giuliani taking over New York City in January 1994, I suspect that many of us tend to think: a city starving for change; a populace placing great faith in the confident, adamantine new mayor as the agent of that change. But actually, neither of these things was quite true.

The city was not starving for change. Bad as the previous four years were—about 1,700 private-sector jobs lost every week on average, homicides surpassing 2,000 per year, more than 1 million residents on welfare—just about half the city was reluctant to give up on its first black mayor, and the voters in November 1993 ratified change only grudgingly. Incumbent David Dinkins was widely seen as ineffectual, but out of 1.75 million votes cast, in so heavily Democratic a town, Giuliani won by just 50,000. If not for the presence on the ballot of a Staten Island secession referendum, which brought the Rudy-friendly voters of Richmond County to the polls in large numbers, he would have lost.

Second, and this is something that’s harder to imagine today, a fair number of people thought: so what? The city was, in the oft-used word of the day, ungovernable. Unsalvageable. The economy was a wreck. Nothing the city did seemed to work. Social indicators were uniformly bleak. In 1993, for the first time, a majority of births in the city were delivered to unmarried mothers. A majority! Also: the drug dealers in the parks. The squeegee men. The homeless. Larry Hogue (no, Google him yourself).

Identity politics run amok. Crown Heights. The Korean-deli boycott. The Rainbow Curriculum (Google it too while you’re at it). You know what I still have on my bookshelf? The first-edition printings of Heather Has Two Mommies and its much less famous companion piece (at least until word surfaced that Sarah Palin had found it unsuitable for the shelves of Wasilla’s library, vastly increasing its eBay value), Daddy’s Roommate. I always thought they’d retain currency value, like records of a lost civilization, written on a faded codex.

No less a savant of urbanism than Daniel Patrick Moynihan, that great liberal and occasional neoconservative who never abandoned his nostalgia for Tammany’s no-nonsense efficiency (“We built the entire Bronx-Whitestone Bridge in 31 months!” he once barked to me), saw nothing but discouraging signs. I remember with crystal clarity the speech he gave to Lew Rudin’s Association for a Better New York in the spring of the 1993 election year. New Yorkers, he said, had withdrawn into “a narcoleptic state of acceptance” of a host of quality-of-life ills and annoyances. The following year, shortly after Giuliani had taken office, Moynihan told a city hearing on juvenile violence that the rate of out-of-wedlock births essentially ensured that the city’s youth was lost for years to come: “The next two decades are spoken for … There is nothing you’ll do of any consequence, except start the process of change. Don’t expect it to take less than 30 years.”

No one quite understood the force of the tornado that had just hit town. By the end of Giuliani’s first year, the city was a visibly different place—made safe, Toronto-ized, starting down the road toward being Olive Garden–ized (yes, there were downsides!); a place that suddenly was no longer the city where Travis Bickle prayed to God for the rain to wash the trash off the sidewalk and where—in real life, not the movies—display ads for porn films actually ran in the Post right alongside the display ads for Smokey and the Bandit (it’s true; a few years ago I went to the Post’s morgue and looked through old issues and saw the ads, and their blurbs screaming “Full Erection!,” with my own disbelieving eyes). That is inconceivable to us now. But it, and a score of cankers like it, used to be the reality in New York. Lots of forces combined to change that, but the biggest force of all was Rudy.

In the intervening years, Giuliani has had his ups and downs. Arguably more downs, at least numerically. Yes, there was the leadership and staggering humanity on display in his response to the September 11 attacks, which counts for a lot. But there was the train wreck of his presidential candidacy. And the train wreck of his Senate candidacy in 2000, which was headed in the wrong direction before his prostate-cancer diagnosis gave him a reason to drop out and focus on his health. The marriages. Judi—yikes! The sometimes unhinged attacks on victims of police shootings. Do you recall the name of Patrick Dorismond, whose sealed juvenile record the mayor ordered released? He was, Rudy said, “no altar boy”—except that he had been, literally. The second-term jihad against hot-dog vendors and jaywalkers.

Six weeks before 9/11, despite all his administration’s accomplishments, his approval rating was just 50 percent, almost exactly the same as his share of the vote eight years previous.

But that number inaccurately suggests stasis, as if nothing had changed from the 50 percent of 1993 to the 50 percent of 2001. And of course that was not the case. If you were here then, you know what I mean. Giuliani represented a completely new model of urban governance. He was not someone who came up through the local Democratic clubs, amassing and owing favors and adjusting himself to the status quo. He was an outsider, a prosecutor, and a hard-ass.

He was lucky too: The local Democratic Party, long ago the pride of Democrats nationally, was sclerotic beyond belief (it mattered that he came to power owing all the local fiefs and mandarins nothing—it allowed him to bang some heads on matters, like the insane cost overruns at Kings County Hospital, which a Democratic mayor, seeking to keep the local peace, would have pussyfooted around). The crack epidemic was, wouldn’t you know it, subsiding. So he had some breaks. But the combination of circumstance and will enabled him to shake up the city like it hadn’t been shaken in years.

It wasn’t all good. Oh, no. His main legacy may always be saving the city, but his secondary legacy will also, always, be that he divided it. Confrontations with black political leaders, sometimes totally unnecessary, antagonized huge chunks of the populace. He wanted, and deserved, the credit for the crime reduction. But that also meant he got, and deserved, the blame for creating the climate that led to what happened to Amadou Diallo (shot 41 times for no crime) and Abner Louima (sodomized with a plunger, for maybe getting into a scuffle with cops when he tried to break up a fight). Diallo, a poor guy from Guinea who was planning to go to computer-science school. Louima, who must have thought he’d successfully gotten out of hell when he left Haiti, and worked in Flatlands as a security guard. We will remember Giuliani on 9/11, absolutely. His name, though, will always be linked to those two names and the divisive legacy they and others represent.

But the Rudy Giuliani of that first year … yes, a definite hard-ass. No doubt of that. But he was a hard-ass about the right things then, when a hard-ass was what the city needed. And then occasionally, when you least expected it, he wasn’t a hard-ass, but a creative chief executive, not firing thousands of city workers in the face of a deep fiscal crisis. I remember going to the mayor’s holiday party that December—my first and last invitation to Rudy’s Gracie Mansion. Donna, then, was the beaming wife, standing before the Christmas tree, bragging about her husband’s accomplishments. There was a lot for her to talk about.

Here was the new white mayor, presented in almost his first week with the perfect dilemma: a racial mêlée.

Things did begin a little strangely. As the new mayor gave his inaugural address on January 2, 1994, his son, Andrew, then a pudgy little 7-year-old, many years and much muscle development away from being the Titleist-crushing young man he is now, stood at the podium with his father. (Rudy, Donna, Andrew, and Caroline were a family then.) He tugged at his father’s pant legs. He squirmed around. He mugged for the cameras. Giuliani’s catchphrase for that speech was “It should be so, and it will be so.” By about the third time, Andrew started repeating it. Rudy laughed. It wasn’t quite as embarrassing as taking a call on his cell from his wife mid-speech. But it was weird. Check it out. It’s on YouTube.

I followed Giuliani around incessantly on the campaign trail in ’93, from Marine Park to Fordham Road. Everywhere he went, he said things were going to be different. Within days, they were.

The immediate task was to handle snowstorms that hit just as he took office. Every New Yorker with a historical memory knows that mishandling snowstorms, failing to sweep the streets of Queens, did in John Lindsay, became the symbol of his lassitude when it came to looking out for the average outer-borough homeowner. Aided by the fine Sanitation commissioner, Emily Lloyd, the new administration dodged that bullet. Then, immediately—something far more totemic.

Giuliani was just nine days into his mayoralty when a call came in to 911 reporting a holdup at 125th Street and Fifth Avenue. The dispatcher’s call didn’t mention it, and one wouldn’t have noticed from the outside, but the third floor of the building housed Mosque No. 7 of the Nation of Islam. When the cops arrived, about a dozen members of the Fruit of Islam met the officers, blocked their entrance to the mosque, pushed officers back down the stairs, and took a gun and a police radio.

Dick Wolf himself could not have invented a more TV-ready scenario. Here was the new white mayor—the avatar of Archie Bunker’s New York to his critics, the man who had campaigned against Dinkins’s capitulations to African-American rioters in Crown Heights and boisterous boycotters of the Korean deli on Church Avenue, the man who fomented a veritable police riot at City Hall Park back in 1992 when he twice shouted the word bullshit into a megaphone as some white cops referred to Mayor Dinkins as “the washroom attendant”—presented in almost his first week in office with the perfect dilemma: a racial mêlée that had the potential to turn into something far larger. The officers made no arrests—they feared a riot. They did work out a deal with the Muslim leaders by which they recovered the radio and gun.

Onto the scene came Al Sharpton and his then-consigliere, C. Vernon Mason, who denounced the police for conducting a “siege” against a place of worship. The story whipped its way through the papers for the next few days, building and building. Sharpton, Mason, and other black leaders kept up the vitriol on their end, demanding an audience. Giuliani and Police Commissioner William Bratton weren’t exactly shrinking violets either, with Giuliani chiding Room 9 reporters for paying too much attention to Sharpton.

Behind the rhetoric, the mayor and police commissioner agreed to have meetings with the mosque’s leaders. Things were, maybe, calming down. But when the NOI leaders showed up with Sharpton and Mason in tow, Giuliani and Bratton abruptly canceled the meetings. “I remember the moment very well,” says Randy Mastro, the deputy mayor for operations at the time. “Rudy said, ‘No, I’m not going to meet with Al Sharpton, and my police commissioner is not going to meet with Al Sharpton.’ ” The NOI leaders came back the next day. They got their meetings. Don Muhammad, a mosque leader, sounded placated. “We do not wish to be seen as persons disrespectful of the law,” he told the Times.

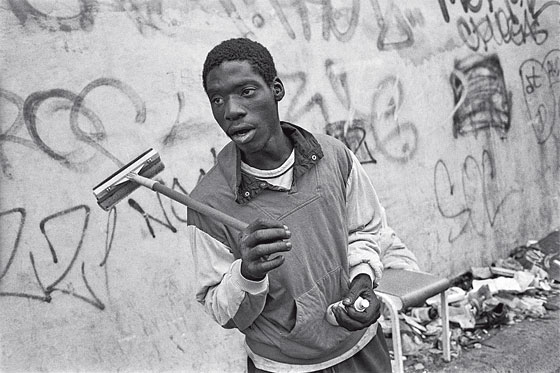

Next up, the squeegee men. Considering that most city residents didn’t drive, sure, maybe they became a somewhat outsize symbol. Giuliani mentioned them constantly during his campaign appearances in 1993 as an emblem of the narcolepsy of acceptance that Moynihan had spoken about. It was difficult to defend a group of men who, no matter how down on their luck, forced their services (which as often as not made car windshields dirtier rather than cleaner) on captive motorists.

But it wasn’t so much that people defended them—although a handful of civil libertarians did, of course. It was more that most people didn’t think the city could really get rid of them. We knew how this worked. They’d just hide for a few days, go somewhere else; if the heat was on at the Triboro ramp, they’d relocate to the 59th Street Bridge. When it hit 59th Street, there was always the Williamsburg. And so on, and so on. It was one of those games of urban whack-a-mole to which there was no end. Just another part of the cover charge of living in New York.

But it turned out there was an end, and, incredibly, a pretty quick one. Once the police finally dug into the matter, they figured out that there were only about 75 or so squeegee men. As Peter Powers, Giuliani’s old friend and first deputy mayor during those early years, joked to me recently, “We found out they were a pretty small union.” They were gone in about a month’s time. Something had gone strangely right. People, however tentatively, started whispering that maybe New York was governable, at least around the edges. “It was very visible,” says Powers, “and it didn’t cost us a lot.”

All right, symbolic measures are one thing. Even first-term governors of Alaska can be adept at those. But governing means, well, governing—digging in to policy, mastering the details, and making sound decisions. Sharpton and squeegees aside, the big bear that Giuliani’s team had to wrestle to the ground in those first weeks was fiscal: a $2.3 billion budget deficit, out of an operating budget that was at the time around $31 billion. More than half of that $31 billion was untouchable—either mandated by lawsuit to be spent on the poor and other services, or city contributions to federal and state programs that couldn’t be cut without risking the matching funding. You see the problem.

“We had found out the size of the deficit during transition,” Powers says. “And we had a month to get a budget in.” So here was a brand-new government, with brand-new commissioners and agency heads, just learning about their departments even as they had to decide how to cut them. The city, of course, has to balance its budget by law. The monitors put in place after the seventies fiscal crisis, and the bond raters, waited like high priests to pass judgment.

The Dinkins administration had balanced four budgets, to its credit, including a $1.8 billion deficit in its first year. But tensions were heightened as Giuliani took office by the presence of something called the Kummerfeld Report, a study Dinkins had commissioned to assess ways out of the crisis. The report, which came out during transition, suggested higher taxes, layoffs, canceling a police class—Dinkins and Albany had just passed legislation expanding the force by a head count of 8,000 in 1991—and putting tolls on the East River bridges. Giuliani rejected every one of these (“Old thinking”), which sounded tough but rather limited his options.

Here, the Giuliani administration made three crucial decisions. First, it would cut department budgets, in some cases painfully; but it wouldn’t touch police, fire, or the number of teachers (the Board of Ed bureaucracy was a different matter). The NYPD was the controversial untouchable, because of longtime battles over police spending versus social-service spending. “But Rudy called everybody in,” Powers says, “and he said, ‘Look, I was elected to cut crime, and I have a plan to do it, and I know it’s going to work. So just get used to it. We’re gonna take the heat.’ ”

Second, the administration worked with Albany to cut a few taxes, most notably the hotel-occupancy tax. That tax, at the time, was 21.5 percent. The city portion was 7 percent. It was lowered by one point. Symbolic, maybe. But still a tax cut. By 2001, hotel tax revenues had nearly doubled from 1994, to $243 million.

Third, the pièce de résistance. Budget-cutting as severe as the kind the Giuliani team faced always involves layoffs. The public-employee unions had all, of course, backed Dinkins. To say they were suspicious of Giuliani would be like saying Jewish voters had a few qualms about Pat Buchanan. “The unions thought this was Darth Vader coming in,” recalls Randy Levine, who was the mayor’s chief labor negotiator in those days. I remember it well: Everyone expected, by the time Rudy and the unions were done waging war, to see the public-employee blood being mopped off the floor.

His great destiny was to be mayor and mayor only—and at a specific moment when the city needed someone like him.

Abe Lackman, Giuliani’s budget director, had different ideas. As Fred Siegel tells it in his book Prince of the City, “Lackman reasoned that the city needed to do more than just cut workers; it needed union cooperation to change some of the work and staffing rules to make city government more flexible.” Lackman was looking for savings, and Levine wanted a whole new approach to the city’s workforce problems. The plan the administration worked out was this: The city would lay off, per se, no workers. Instead it would offer severance packages—a lump-sum payment and health-care benefits for one year— encouraging employees to leave the public sector and seek private-sector jobs. In return, the unions would agree to greater flexibility in hiring rules. For example, the city could transfer employees from Department A to Department B based on need, rather than having to continually go through an entire hiring procedure when a Department B vacancy popped up.

The task of negotiating the deal fell to Levine, a lawyer who’d been a labor negotiator on the management side. “I took it to Rudy, ‘In the private sector, this is the way you do it, so why don’t we do it this way in the public sector,’ ” Levine recalls. He went to the unions with the plan and one reassuring statement: “I never in my fourteen years [of doing this] tried to break a union.” The labor leaders were taken aback. The plan sailed through. Savings. No blood.

It would be three or four years before Giuliani really got the budget under control. But I’ve always thought that the severance deal was one of Giuliani’s great accomplishments. It placed on display not his bullheadedness, but another leadership quality that we never saw quite enough of, one that was important to his success: his iconoclasm and willingness to depart from received wisdom. It played against type. Unlike a lot of things he subsequently did, it cooled heads and fostered community.

When Giuliani said to Powers et al. that he had a plan for reducing crime and knew it would work, he wasn’t actually talking about his plan. And that’s okay. Mayors administer lots of things other people conceive, and ultimately they get the blame or the credit, and deservedly so.

The first revolutionary idea—simple, like most revolutionary ideas—was Jack Maple’s, and it hit him one night in early 1994 while he was sitting in Elaine’s.

The story has been amply and ably chronicled in this magazine’s pages and elsewhere, but quickly, two points: First, for years, or decades, the various bureaus of the NYPD had worked as separate fiefdoms. There were nineteen separate data-reporting systems within the NYPD, and virtually no one had access to all of them. Second, incredibly enough, the NYPD was not in 1994 chiefly a crook-catching enterprise. Years of internal restructurings had made the department reactive rather than proactive. In 1993, the average cop made fewer than a dozen arrests.

Maple, that night, wondered what things would be like if he could get all the crime data for a particular precinct—he conjured East New York, one of the city’s roughest neighborhoods—and send the cops of that precinct out to … make arrests! The crime and arrest data brought together.

This was the germ of what would become known as CompStat, the computerized crime-tracking system the NYPD instituted under Maple and Bratton. CompStat was used throughout the city. If you lived here then, you may remember reading the stories about Giuliani and Bratton’s weekly meetings with precinct commanders, raking them over the coals if they didn’t get results. (The famous Giuliani-Bratton fallout, when the thin-skinned mayor fired America’s best police commissioner for the sin of appearing on a Time cover without him, didn’t happen until 1996.)

The other idea, of course, was the “broken windows” theory, for which chief credit goes to criminologist George Kelling. A few broken windows will lead to a few more broken windows, which will lead to larger blights; so fix the problems when they’re small. When the transit cops started arresting people for fare-jumping, previously considered too penny-ante to worry about, they found that fare-jumpers often had rap sheets including more serious crimes. When street cops started busting people for selling dime bags, they found the same thing.

Crime had dropped by 7 percent in 1993, under Dinkins. In 1994, it dropped by 12 percent. Then 16 percent in 1995 and another 16 percent in 1996. Homicides—2,262 in 1992—went below 1,000 for the first time in decades in 1996, then down to 746 the year Giuliani sought reelection. Now we’re back to pre-Beatles numbers, and New Yorkers take it as a given. But I remember very clearly: The drops in ’94 and ’95 were so astoundingly steep that it was downright confusing. It just didn’t seem possible. Something had to be wrong with the numbers.

But people had started to believe. “We were always thinking about, ‘We’ve got to show that the city is governable,’ ” Powers says. “That was always the most important thing.”

There was more on the way. The slashing of the welfare rolls, under top adviser Richard Schwartz, was planned in the latter half of 1994, but it wasn’t really implemented until 1995, when Giuliani highlighted it in his second State of the City address. But by the end of 1996, the city’s welfare rolls had declined from nearly 1.2 million to 950,000, and they kept declining thereafter. Some aspects of the workfare program were more punitive than perhaps they needed to be—over time, the city loosened regulations to include more education and job training as acceptable substitutes for work, which was not the case at first. But this, too, was clearly something that needed to be done, and the critics’ most cataclysmic predictions did not, somehow, materialize.

Cleaning up the Fulton Fish Market was another project that had its origins in late 1994 but didn’t really come to a head until the following year. By early 1995, the administration had crafted legislation giving the city the power to take “good character, integrity, and honesty” into account when granting licenses to do business there. There was an arson fire. The city got the market reopened within 24 hours. The mob helped initiate a wildcat strike. Giuliani said to the strikers if you don’t come back to work, we’ll reopen it with all new people. “I mean, that’s what you call guts,” says Randy Mastro, who was in charge of the fish-market operation.

What else? Remember Giuliani’s endorsement, in his first year, of Mario Cuomo? Now, that was guts, too. Giuliani did it partly because he hated D’Amato and knew that if Pataki became governor, he’d have a competitor for biggest dog in the GOP (a competition that Pataki ending up winning, I’d say, in some ways, except for the fact that Rudy is much the more memorable figure), and partly because he needed Cuomo’s help with the city’s finances and on Medicaid formulas. Then he barnstormed the state on Cuomo’s behalf, warning about the plague of corruption that would descend on us if Pataki were elected. That turned out to be sort of true, though not quite to the extent that average people really noticed.

There’s one way of measuring a politician’s success. The things he did in his day that were controversial—are they accepted wisdom now? One can’t say “yes” to that question about everything Rudy did, by a long shot. But as far as that first year is concerned, this is true: No person could run for mayor and be taken seriously by saying or suggesting that he or she would depart radically from the basic path Giuliani set in 1994–95. Bring in more accountability, apply a new and needed standard of civic behavior, be forceful but fair with the unions, get the cops out on the street, prove that things that were broken could be fixed. It couldn’t be done. The local Democratic Party, which I scolded eleven years ago in the pages of this magazine (“Four Candidates and a Funeral,” May 12, 1997) for its tectonic adaptation to the new rules, has learned this lesson too slowly.

Or has it even learned it yet? Bloomberg learned it—and proved, by the by, that you don’t have to behave like an ogre to get results. That combination, success and civility, is why they tell me he’s probably on his way to getting the term limits undone, something Rudy could never do.

You noticed, recently, something else Rudy couldn’t do: get himself elected president. Long ago, A. J. Liebling wrote a wonderful book on Earl Long called The Earl of Louisiana. The first sentences of the book are pricelessly memorable: “Southern political personalities, like sweet corn, travel badly. They lose flavor with every hundred yards away from the patch.” Great stuff. But these days, the opposite is true: We’re up to our non-red necks in Southerners, God help us, and it’s the New Yorkers who don’t travel well. Giuliani trying to seem like a right-wing nut just didn’t fly. Watching him defend Wasilla, Alaska, in his convention speech was a hoot. This is a man who hates leaving the Upper East Side for more than a few hours at a time. That’s why this governor talk doesn’t really make any sense to me. He could barely drag himself to Westchester in 2000, let alone the Western Tier.

No—his great destiny was to be mayor, and mayor only. And I might even say: at that moment only, when the city needed someone like him. Remember how often people talked in 1992 and 1993 about giving up on the place. Within one short year, or even less, people weren’t saying that very much anymore. For all the Rudy- craziness that later ensued and that darkened his legacy—the bashing of police-shooting victims and Brooklyn Museum artists and ferret lovers and his second ex-wife and of course Hillary—it has to be acknowledged that he was the man for the moment. There probably won’t be a moment in New York quite that desperate again in our lifetimes. He helped make sure of it.