On Wednesday morning, March 11, 2020 — just over a year ago — there were only 20 known cases of COVID-19 in Los Angeles County.

I hauled my 20-month-old son Desi through the airport in the same backpack we used on hikes — the easiest way to keep him from touching anything. The Delta terminal at LAX was quieter than usual but still bustling, and while the TSA agents had added rubber gloves to their ensemble, nothing seemed all that different from the last time I’d flown earlier in the year. In line to board the plane to Detroit, I counted four people out of a hundred wearing masks. Desi stared at them with wide-eyed intrigue, not sure whether to laugh or to be afraid.

It’s not like the pandemic had caught me by surprise: I’d been following the coronavirus story since just after New Year’s, when I saw online video clips of sick patients overwhelming a hospital in China’s Hubei province. By February, the virus had surfaced in the U.S., and had sparked a lethal outbreak inside a nursing home in Washington state. It was easy to imagine that the virus would eventually spread across the country, but the threat still felt strangely abstract, like a brush fire on a distant ridge.

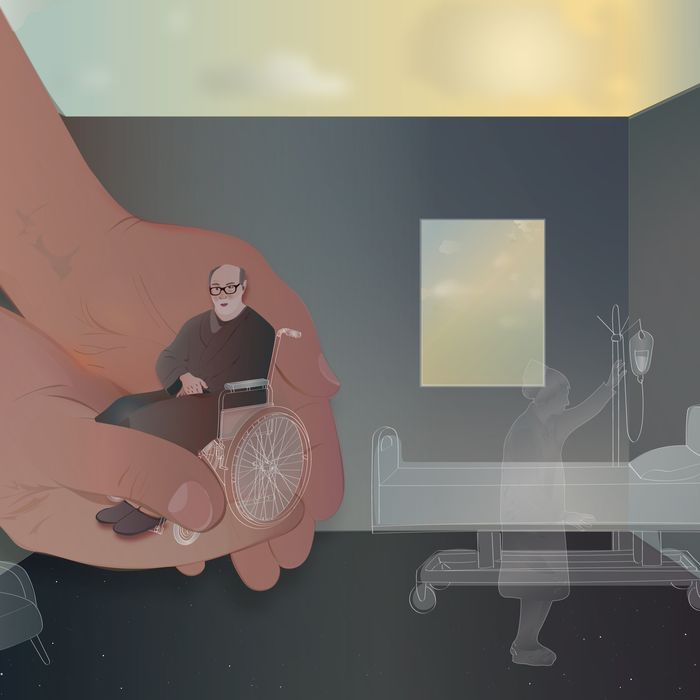

At the same time, I knew that my dad, who lived in a nursing home in Michigan, was in grave jeopardy. In 2018, he’d suffered a massive stroke, was given a 3 percent chance to survive the week, and had miraculously recovered well beyond every doctor’s highest expectations. Now, two years later, he remained mostly bed-bound, frozen on the right side of his body, with limited speech, but otherwise very much himself — cogent and present, able to hold up his end of a conversation through facial expressions, a jolly thumbs-up, and a few words here and there.

His nursing home, covered by Medicaid, provided him with a reliable baseline of care: “three hots and a cot,” as I often joked with him — just like prison. But I knew COVID-19 was bound to eventually reach the Midwest, and that my dad, at age 83 and weakened since his stroke, was at serious risk. Catching COVID, for him, would likely be a death sentence.

It would be tough, I felt, to size up his safety at the nursing home and weigh all of his options from all the way across the country. And I wanted one more chance to see him, in case the worst came to pass.

For two years, we’d been facing the prospect of eventually losing my dad, but once he’d survived his initial stroke, the idea of his mortality had grown more distant. Now it suddenly felt vivid and close at hand, like we’d reached the final pages of a treasured book. I felt sad and frightened and helpless — so I booked a flight from LA back home to Michigan, along with my son Desmond, whom we call Desi, born the summer after my dad’s stroke.

Aboard the flight, I took our window seat and pulled Desi close, relieved that the middle seat was empty but unsure how I was going to manage the next several hours. I’d been trying to keep myself from rubbing my eyes, scratching my nose, and tugging at my bottom lip — and I was struggling.

The idea of keeping a not-quite-2-year-old from constantly touching everything around him, then plunging his hands in his mouth, seemed far-fetched. With a few Clorox wipes, I wiped down our seats, the armrests, the window shade, the seat belt, the TV touchscreen, and the rest of the seat in front of us. Meanwhile, in the aisle seat, a man in his 60s wearing a USC Baseball jacket watched with a bemused look. “Just being extra careful,” I said, feeling sheepish. “We’re visiting my parents, and they’re kind of high-risk. Hey, want me to clean your screen?”

The guy waved me off, then donned headphones and started swiping through the TV options before popping open a bag of Doritos.

Five hours later, on the ride to Ann Arbor, I checked my phone and scrolled through headlines: The entire San Francisco Bay Area had shut down. Schools were closing in L.A. The next one made my heart freeze: Michigan had notched its first two cases of COVID.

When we’d left our house that morning, we could feel a storm brewing, even if the skies were sunny and clear.

Now, the storm was here.

Hindsight has an odd way of making even the most shocking things feel predictable. In the past year, more than half a million Americans have died of COVID-19 — including people I’ve known and loved. In my circle of friends, a few have lost a parent to COVID; one unlucky soul lost both. Countless others have had to make impossible decisions to best protect their loved ones, with limited information and often from thousands of miles away.

Throughout, a heartless narrative has arisen from certain corners: that the lives of older and medically vulnerable people are expendable, that they can be sacrificed so that daily life for the rest of us can continue without cumbersome restriction. That they must die so the economy can survive. It’s a line of thinking so wantonly cruel, I can’t fathom how anyone could subscribe to it. But, like other global scourges — racial and religious oppression, war, famine — I suppose if you haven’t personally been touched by COVID’s dark specter, there’s a way to keep it compartmentalized.

I never could. The threat to my parents felt dire and desperate from the moment COVID reached our shores. And now, a year later, as the death toll continues to climb with metronomic persistence, a thousand more lives every day — I am struck that everyone who succumbs to COVID is somebody’s mother or father, son or daughter, brother, sister, colleague, neighbor, friend, or loved one. And that the pandemic’s victims include not only those who died of disease but those friends and family members who felt the same dire desperation to keep them safe — but could not.

The number 500,000 is almost impossible to grasp — but, for me, the most vivid way to think of it is to picture filling every seat in Michigan Stadium, in my hometown of Ann Arbor, about five times over. It’s the largest stadium in the country and one of the largest in the world, a place my dad and I have been going to watch college football games since I was a kid. I imagine that stadium filled to the brim on a fall Saturday, an overflowing mass of humanity, and then I imagine what it would feel like to know that every single one of those people was dead. Then I repeat that four more times. (Before long, I worry I’ll have to repeat it a fifth.)

Yet somehow, no matter how nightmarish the daily and cumulative tolls might be, we’ve also grown used to it. What would have seemed like an implausible, dystopian vision of the future, if shown to us ahead of time, has now, in many ways, become old hat.

Our ability to adapt while under siege is a powerful survival mechanism. But part of what it means to adapt is to forget. This is one reason, I think, that I’ve found myself drawn again and again to the memory of those days last March — so recent and so far away — as we transitioned from our former reality into the sad, bitter, and bewildering one we soon found ourselves in. I’m scouring those early moments: the rush of fear, the hurried trip home; and I’m inspecting them like beach glass, reflecting on what we left behind and where we’ve arrived — and how we passed from one reality to the other.

At my parents’ house, my mom was delighted to see me but especially to see Desi. In turn, Desi was excited to see her but mostly excited to see her dog, a humongous black collie named Banner. As Desi teetered around the dining room, the dog hovered close, poking Desi’s face with his long snout and licking Desi’s hands and chin and the back of his neck, while Desi giggled and cried out with glee.

It had been three months since our last visit home, and my mom marveled at how much Desi had grown. In December, Desi had still been a baby — less independent, less aware — and now, he could walk and talk well enough to confidently say, “Hi, Grandma!” My mom is deaf — she lost her hearing in 1972, through an illness, at age 29 — but she’s a skilled lip-reader. “Did he just say, ‘Hi, Grandma?’” she asked me, amazed. I nodded. Smiling, Desi said it again.

Later, after I’d set up Desi’s crib in my old basement bedroom, plugged in his baby monitor, mini-heater, and white noise machine, and put him to bed, I joined my mom at the dining table for a late meal.

“How are you?” I asked her.

“I’m tired,” she said. “I’m just really tired.” Since my dad’s stroke, my mom had been single-mindedly devoted to his recovery. The first few weeks, she’d spent her days and nights at his hospital bedside, helping him find the will and strength to live. Then, after a couple of months, once my dad’s medical condition had mostly stabilized, she’d managed his transition out of the hospital, spending their 50th anniversary in his new room at the nursing home.

Medicaid covered basic room and board but none of the physical therapy and speech exercises that might help him build enough strength and independence to one day move back home. So in DIY fashion, she’d also rallied a motley, improvised crew we called “the Care Team” — nursing students and old neighborhood friends of mine who could drive his rehabilitation forward, paying them $15 an hour out of her meager earnings as a meditation teacher.

Against all odds, my dad was living a meaningful life again. And it was mainly due to my mom’s constant, persistent, and devoted efforts — an incredible feat, all in all, for a woman who was nearly 80 herself and had her own health issues. The irony was that before my dad’s stroke, it was him who’d been helping to take care of her, taking out the trash and recycling, going for groceries. Beyond her deafness, her vision had faded, which made it harrowing to drive more than a couple of miles, especially at night. Because of her bad knees, she used a walker to get around the house and a motorized scooter at the grocery store or the park. Diabetes and high blood pressure were growing concerns.

Now, just as they’d completed the worst kind of marathon and had at last found stable ground, COVID had appeared. It was too sorrowful and exhausting to contemplate. “We can’t move him home,” she said, despairing. “I can’t give him the care he needs. But to leave him at his nursing home could mean he just dies.”

Half an hour outside Ann Arbor, my parents owned a ragged, rustic cabin, with electricity but no running water, in the woods near a tiny inland lake. I fantasized about breaking my dad out of his nursing home, bringing him out to the cabin, and caring for him myself. We’d play euchre, watch old movies on VHS, and listen to ballgames on the radio, until the pandemic tucked its tail between its legs and skedaddled off into the brush.

Of course, a fantasy is all it was: Caring for him was more than one person could manage, I had my own family to take care of, and there wouldn’t even be any ballgames to listen to.

Still, I knew there had to be a way to keep him safe.

In February 2018, I was in the town of Why, Arizona, outside of Organ Pipe National Monument, on a road trip with my wife, Margaret, who was several months pregnant. One morning, I woke up to a strange jittering movement in the bed. Our baby was bopping around inside her, the first time I’d ever been able to feel him kick. It was a thrilling, if surreal and shocking sensation. When I pressed gently back, he jabbed his feet out again: our first little game.

After a strange, joyful 20 minutes, Margaret grew sick of it; after all, she’d been feeling his kicks for weeks. She climbed out of bed and I reached for my phone, only to discover a dozen texts and missed calls. Scrolling through them, I froze in alarm. During the night, my dad — my strong, healthy, buoyant dad — had collapsed in the kitchen. My mom had discovered him, hours later: eyes open, blood seeping from his nose and mouth, a bowl of ice cream melted on the counter. Now he was in the hospital in a coma. If I wanted to see him alive, I was told, I should try to get home immediately.

By midnight, my mom, my two brothers (in from New York and Seattle), and I had gathered around my dad’s bed in the neuro ICU at the University of Michigan hospital. We talked to him and sang him songs, though we knew he probably couldn’t hear us. His brain had bled so terribly that doctors’ hopes for recovery were close to zero. The idea that my dad would never get to meet my child — his new grandchild — was especially heartbreaking. Yet somehow, a day at a time, he stayed alive, wrapped in tubes, a ventilator pacing his breaths, until at last he came awake, regained strength, and was well enough to transfer out of the hospital to the long-term care facility where he’d been for the past two years.

Now, as COVID cases began to spread in the U.S., I’d landed again in Michigan to see him for what I was afraid could be the last time. The plan for the week was for two members of my dad’s Care Team, a young couple named Kaitlin and Phil, to pick my dad up at his nursing home around 9 am and bring him home for a visit before taking him back that night; he often visited the house for a few hours at a time before the pandemic.

So when I woke up at 10:30 and the house was quiet, I knew something had gone wrong. I left Desi sleeping in his crib and slipped upstairs. In the living room, my mom sat quietly with Kaitlin and Phil. My dad’s nursing home, they told me, had jumped into lockdown mode that morning. Kaitlin, as my dad’s registered personal care assistant, had been allowed to go inside to see him, but family visitors were now prohibited. The mood in there was tense, she said, and my dad was scared. Even before COVID, he liked to watch CNN around the clock. Like me, he’d followed the coverage of the nursing homes in Seattle that had been wracked by infection, and he was clear-minded enough to understand just how much danger he might be in.

Our first thought, of course, was to try to bust him out of there and bring him home more permanently. But his care required more resources and expertise than we could ever manage on our own. No matter that his mind was sharp; his body had its major limitations. He needed to be changed several times a day — a two-person job. Every hour or two, he needed help shifting position to avoid bedsores. He needed an on-call nurse, 24/7, available at the touch of a button, and a doctor on site to monitor his blood pressure, blood sugar levels, and other vitals on a daily basis. Even if I were to move back into the house myself, it was way more than I’d be able to handle on my own.

I felt like I was going to cry. I couldn’t believe that had we arrived one single day earlier, Desi and I would have had a chance to see him, and that now our chance was gone. My mom seemed equally distraught: After nearly 52 years of marriage, would she ever see her husband again?

I’ve seen, in the year since, so many friends wrestle with the same kinds of regrets — punishing themselves over missed opportunities for extra time with loved ones: a family vacation never taken; a holiday visit they’d postponed; words never spoken, until it was too late. COVID arrived with a suddenness that few could predict, and sparked outcomes few of us could have foreseen.

“What if Phil and I moved in here?” Kaitlin said slowly — not suggesting it, so much as playing out the possibilities in her head. Her sense, she told us, was that, after two years in the nursing home, my dad, physically, was entirely stable. He no longer had tubes in him to administer food or fluids. She knew what medicines the nurses gave him, and in what quantities. As for checking his vitals, it was nothing she couldn’t do easily herself.

Over the baby monitor, I heard Desi crying. He’d come awake in a dark basement, with no one around, and I knew he must be confused about where he was. The four of us agreed that we’d take a day to think things through. But we knew, if we were going to really try to bring my dad home from the nursing home, we’d have to quickly take decisive action. While my dad’s nursing home had let Kaitlin in that morning, there was no telling how their rules might shift on her next visit. And if COVID cases were already being confirmed in neighboring counties, it meant that undoubtedly it had already begun to spread closer to home.

Like every parent, parenthood changed me. While I managed, vaguely, to keep up with work, keep playing sports, keep being creative, and keep seeing friends, my old life had quickly receded. Nothing really mattered to me as much as the time I spent with my son. It was joyful and meaningful, beyond all expectations, to watch Desi evolve each day and begin to discover the world.

What was most unexpected, though, was all the ways my dad’s traits and habits began to sprout in me the moment Desi arrived. My whole life, I’d mostly been annoyed and embarrassed by my dad’s constant singing, and now, bizarrely, I found myself singing all the time — relentlessly, and with unrestrained zeal. It was for Desi’s benefit, since singing seemed to soothe him, I told my wife, when she begged me to lay off. Just like my dad, I’d make up songs about nothing and everything: hits like “Diaper Time,” “Being and Peeing,” and “Let’s Treat Mommy Right.”

Over Skype, I shared the songs with my dad at his nursing home, so he could learn the words and sing along. Although it was hard for him to say the name Desi or Desmond — since the stroke, many words eluded him — we experimented one day and realized that it was easy when incorporated into a song. My dad found a tune and began to sing: Desmond, Desmond; Desmond, Desmond. I whinnied a line, in an Irish accent: “I’d sail the seven seas, to see my wee laddie,” and my dad launched back into his chorus: Desmond, Desmond. I tried another line: “My grandson is a king; he makes me want to sing.” And my dad chimed back in: Desmond, Desmond. We made up a dozen verses, and returned to that song again and again.

Now my dad was all alone, a few miles away, as a killer virus closed in, and I had only a few days in town to do what I could to make sure he was out of harm’s way.

The morning after we arrived in Michigan, I popped Desi into the backpack and carried him down the street to a playground, while my mom cruised alongside us in her scooter, her collie Banner in tow. This was before most playgrounds had been closed off, but it was surreal to be with my mom and my toddler son at the tamest, most ordinary and innocent place imaginable — an empty grade-school playground — and feel confronted with matters of life and death.

“What do you think?” I asked my mom, as Desi explored a plastic fort. “Should we really try to bring Dad home?”

“I wish the house was ready,” she said. We’d have to quickly locate and buy or rent a hospital bed. His wheelchair could only fit through the front door and the back door, and not into any of the bedrooms, so he would have to live in the living room. And since there was no way to get him into the bathroom for a shower, he’d need to be bathed in bed.

“And I wish he was more ready,” she added.

Slowly, incrementally, my dad’s strength had been increasing. With continued work, in six months or a year perhaps he could learn to transfer himself out of bed into his wheelchair, to dress himself, and even to use the bathroom by himself, dramatically reducing the level of care he needed. But these progressions, while in the realm of possibility, were far from likely, at least anytime soon.

If my mom was at all resistant, she told me, it was because after two years of mourning the life with my dad that she’d lost, the life they’d had for 50 years, she’d recently found herself letting go of what was in the past and adjusting to life on her own. After a long, dark, painful period, she found herself, at last, emerging back into the light. To shake everything up overnight was frightening.

There was also the expense involved. Through a GoFundMe campaign and her own fundraising efforts, essentially begging friends, extended family, and the spiritual community she’d led for decades for support, she’d raised enough money to keep the Care Team mobilized for another year, maybe a year and a half. But if my dad came home and Kaitlin and Phil moved in to take care of him, their hourly wages, as reasonable as they were, would mount impossibly fast — not to mention the costs of the daily medications and medical supplies now covered by the nursing home through Medicaid. “We’ll burn through that money in two months,” my mom lamented. “Then what?”

That said, she couldn’t imagine the idea of leaving my dad on his own. “It’s not coronavirus I’m most afraid of,” she said. It was what might happen to my dad if he was left alone at the nursing home for weeks or months on end, while his nursing home was on lockdown, with no visits from the Care Team and no visits from her. “It just breaks my heart,” she said. Banner, sensing her mood, moved close and dropped his head into her lap.

Back at the house, as Desi played with blocks, Banner beside him, I called a local elder-care lawyer named Reid, who’d gone to high school with my younger brother. Reid had been a godsend to us since my dad’s stroke, helping us navigate various state bureaucracies to get my dad enrolled with Medicaid and admitted into a nursing home. My first question was if we’d even legally be allowed to pull my dad out of his nursing home.

“He’s not a hostage,” Reid said. The on-site doctor would have to sign off on it, but if we wanted my dad home, we could surely sort out permission. “But you want my advice?”

“Please!”

Reid paused: “If it was me, I’d leave him where he’s at.” Reid knew how limited our finances were, and how little support the state of Michigan offered to people in our circumstances as far as home care. “I just don’t think your family can afford it,” he said.

But he offered a promising compromise. The residents at his nursing home were allowed what was called “therapeutic leave” — a chance to dip out of the nursing home here and there, for a maximum of 17 days per year. If we really wanted to, Reid said, we could always try bringing my dad home for a couple of weeks, and then reassess. While our goal had always been for him to one day move home permanently, this could allow for some helpful wiggle room.

After hanging up, I called my dad’s nursing home directly to speak to the infection control nurse. I told her how worried I was for my dad. “I get it,” she said. “I would be, too.” But she sounded confident. For a few minutes, she detailed their infection control procedures. Nurses and aides were required to wear gloves and masks. She’d been having individual conversations with each staff member to help ensure they understood the gravity of the situation. And they’d been increasing the frequency in which both the residents’ rooms and public spaces were cleaned.

“If this was your dad,” I asked, “what would you do?” It felt strange to pose the question in such a personal way, to ask someone, essentially, how good they were at their job, how much faith they had in their own abilities.

“You know,” she said. “I really don’t know. Other people have been asking me that.” Her voice grew distant, like she was talking to me from the other side of the room. I pictured her getting up to close the door to her office. At last, she went on, confidentially: “I guess if it was my dad, I’d try and bring him home.”

Now that a year has passed, COVID deaths in US nursing homes have surpassed 125,000, and long-term care facilities have been called “death pits” on the front page of the New York Times. It might seem strange to remember a time when we might have considered testing fate and leaving my dad at a nursing home. But at the time I arrived in Michigan, only a handful of nursing homes had been affected. There was some hope that with the right protocols in place, a facility could remain COVID-free.

That view has proven to be naive. Almost universally, COVID finds a way in. Thousands of elder care facilities have dealt with COVID deaths among residents. And beyond the nursing home’s elderly victims, hundreds of thousands of staff members have fallen ill themselves (though residents, many ill and vulnerable, have died in far greater numbers). Among my friends, several have lost their parents to COVID at facilities like my dad’s nursing home. Did they, too, agonize over whether to pull their parents out? I’m not sure, and it seems cruel to ask now. But I know that people everywhere were — and are — wrestling with similar choices while confronted with limited and conflicting information, as well as their own unique situations.

By Friday morning, March 13, President Trump had declared a state of national emergency, and Kaitlin went back to visit my dad at his nursing home. She texted me a picture: two empty boxes of rubber gloves from the rack in my dad’s room. The infection control plan was already flatlining.

Briefly, with Kaitlin’s help, I FaceTimed with my dad. He had a chaotic look in his eyes. I tried to keep a brave face but was at a loss for what to say to him. He’d been watching CNN, just like everyone else.

“Dad,” I said, “I know it must be really scary right now. We’re gonna do everything we can to help you stay safe.” I didn’t want to suggest that we were going to move him home, since I still didn’t know what was possible. For a couple of minutes, I dangled Desi in front of the camera, in an effort to keep the mood upbeat. Desi seemed to catch the frantic edge in my voice and to somehow understand that he was being used as a prop, which he resented; he protested by going limp in my arms. Then, without a goodbye, the connection cut out.

An hour later, Kaitlin and Phil came by the house. The scene at the nursing home was rough, Kaitlin said. Already, staff was missing. There was a handwritten sign taped to the front door that said NO VISITORS ALLOWED, but nobody at the entrance to enforce it. Stuck in bed, his routines disbanded, my dad appeared to already be losing it.

“We’re down to try and get him home,” Kaitlin said. She and Phil had talked about it and felt it was the only thing to do. As long as they could bring their dogs along, they could decamp from the farm where they lived and move in with my parents, sleeping in the basement and giving my dad the care he needed. They’d keep him clean and well fed, and even continue his exercises and PT to the best extent they could, without access to a gym or a pool.

They couldn’t stay forever, but at least a month or two, until we’d found other caretakers or another longer-term solution. And, critically, they would do it for a rate my family could afford, what amounted to a few bucks an hour. All in all, it was a moving, almost unbelievably generous offer — downright heroic. They said they’d give my mom and me some time to discuss and left to run some errands.

“What do you think?” I asked my mom, Desi balanced in my lap. Would Kaitlin and Phil be able to manage on their own? Who would succeed them? And what if someone — even my dad — brought the virus into the house, so that not only my dad’s life was in danger but my mom’s life, too?

My mom seemed equally nervous and excited. But after 10 minutes of discussion, she said at last, “I think we should do it. What’ll be, will be.” She shrugged, flashed a wide smile, and gave me a fist pound. We quickly began hashing out our next steps.

First, we’d get the doctor’s approval to get my dad discharged, at least for a temporary “therapeutic leave.” Hopefully, the move would be more permanent, but at least this way we could hold his room for a little while to see how things shook out. We’d also have to quickly get a bed for him, and transform the living room to comfortably house him.

And we’d have to see what resources might be available from the state for additional care support, since no matter how valiant and motivated Kaitlin and Phil might be, here or there they’d surely need a break. Talking through these logistics felt giddy and surreal. Although I’d dreamed that one day my dad might be well enough to move back home, it had mostly seemed like a fantastical notion, like sending astronauts to Mars. But now, suddenly, it was happening.

When Kaitlin and Phil came back to the house, my mom and I told them it was a go. “Thank you,” my mom said, hugging each of them, a bit emotional. She seemed, at the same time, to be both relieved and scared.

“Thank you for trusting our instincts,” Kaitlin said. She suggested we make the move on Tuesday morning. That would give my mom and me three and a half days to get the house ready.

They drove off and I hurried to get Desi dressed in warm clothes, and loaded him, Banner, and my mom into her minivan for an afternoon field trip. Before we could go shopping for beds, we were going shopping for burial plots.

Forest Hill Cemetery, founded in 1857, sprawls across 65 acres on the edge of downtown Ann Arbor, tucked between the University of Michigan and the Nichols Arboretum, beside the Huron River. At its main entrance, a massive Gothic Revival stone archway greets visitors, before a maze of narrow dirt roads that split off among towering oaks and maples and grassy inclines quilted by thousands of tombstones.

Over the years, my parents had occasionally mentioned the idea of stopping by Forest Hill to pick out burial plots, but only in the way they might talk about planting turnips or visiting Montreal — something to do one day.

Even after my dad’s stroke, there were always other things that needed to be done, and I could understand how it might not be the cheeriest task. Life is littered with these kinds of rotten chores, ripe for procrastination. The tasks, the conversations, that we avoid until we can’t, hoping to avoid the discomfort that comes with them. But now, with COVID coiled and ready to strike, choosing plots for my mom and my dad was finally on the front burner, and I’d made an appointment with the Forest Hill caretaker.

“It’s not like we’re expecting you or dad to die anytime soon,” I assured my mom, though we both knew that was only a cloudy partial truth. My brothers and I just didn’t want to have to end up making a decision for my parents that should rightfully belong to them.

We pulled up and my mom pushed her walker inside the old stone hut — built before the cemetery first opened — that the caretaker used as an office, while I lifted Desi from his car seat and followed her in. The floor, made of bowed, ancient wood, creaked under us, and in the deep darkness of the room, behind an enormous desk and lit in the pale yellow glow of a dying lamp, sat the caretaker, a man in his late 60s, with glasses and a voracious mustache.

He had the solitary vibe of a lighthouse keeper, but smiled when we came in and rose to greet us. “Hi there, I’m Larry,” he said kindly, lifting his hand. I leaped over to grasp it before my mom had a chance, like a presidential bodyguard diving in front of an assassin’s bullet. I’d warned her not to shake anyone’s hands but knew she still hadn’t absorbed it.

I took a seat, immediately squeezed sanitizer into my hands, and rubbed them together in the obsessive manner I’d recently learned from online videos. Larry gave me a peculiar look. “Strange times,” I said, not wanting to offend him. “Gotta be so careful. You know. With the coronavirus and all.”

“I keep hearing about that,” Larry said, like I’d mentioned a new buffet restaurant in Arborland Mall. One man’s global crisis, I could see, was another man’s idle footnote.

Larry passed a pair of Forest Hill pamphlets to me and my mom. He began breaking down the various costs in what I came to understand was a well-rehearsed but low-pressure sales pitch, and it occurred to me that people must comparison-shop for gravesites the same way they do for refrigerators.

I began translating it all into sign language for my mom, but she cut him off. It was her style to be direct, since her deafness could make communicating with strangers a challenge, and she’d learned to minimize small talk and focus on the essentials. She spoke to him bluntly: She wanted two plots. If possible, far from the traffic on Geddes Avenue and close to the arboretum. There wasn’t much more to it.

“Okay,” Larry said. “Let’s go take a look.” From a high shelf, he retrieved a mammoth, ragged tome, itself the size of a granite tombstone slab, then led us outside, where he climbed into his old pickup truck and asked us to follow in my mom’s van.

For the next hour, we cruised along the cemetery’s winding roads, while I made up silly songs for Desi to keep him mellow. Every few minutes, Larry pulled to a stop, stepped out of his truck, dragged on a cigarette, and pointed to an open patch of grass partway up the hillside where my mom and dad might one day rest in everlasting peace. “I don’t think so,” my mom said to me. “Too close to the road.” Or: “That one’s not bad. But we can do better.”

Finally, at the cemetery’s very last row, where it abutted the Arboretum, separated by a black iron fence, the truck stopped and my mom said, “This is the place. This is gonna be it.”

Larry took a few steps onto the grass and pointed to a high groove in the shade of a hickory. “I’ve got two plots there,” he said, “but here’s the thing. They’re not side by side. They’re head-to-head. Like, the long way.”

I explained this to my mom. “Really?” she said, and began to laugh. “I always pictured me and Dad next to each other, not with just our heads touching.”

“You could have your toes touching,” I offered.

“Or his toes in my face,” she said, laughing harder. “Smell those stinky feet in the afterlife.” Then she sobered. “Let me get out and take a look.” I helped her out of the passenger seat, down to the muddy road, and let Desi loose from his car seat so he could roam.

We fell silent, and for a moment, time seemed to fold in on itself. My mom had sunglasses on, but I could see that her face had taken on a queer expression. “I wish we’d done this a long time ago,” she said. “It wouldn’t have felt so … imminent.” She paused. “But I think this is it. What do you think?”

“It’s a beautiful spot,” I said. “It’s really up to you.”

Meanwhile, Larry lit a fresh cigarette as he studied the pages of his cemetery treasure map. “Hey, I found something,” he said. Fifty feet up the road, there were two plots in the same grove of trees, with the same view, but side by side. We all made our way over, and my mom took a look and nodded. We had our spot.

Driving back to the house, I imagined — years into the future — visiting my parents’ graves with Desi, who’d grown to be a teenager, as tall as me. I could see myself telling him stories about his grandparents and what they’d been like. It was an aching feeling, to picture both of them gone. Then I wondered, would Desi do the same with his children, when I was gone? Would I be buried there, too?

I snapped out of it. To spend time right now mourning my parents’ death — or even my own — would only risk squandering some of the precious moments I still hoped to have with them in the days to come. I looked over at my mom and saw that her eyes were wet.

“You okay?” I asked.

“I’ve lived a wonderful life,” she said, rubbing tears away. “But I want to keep living. I’m not ready to go. I want to see Desi grow up.” With that, I found that my eyes were wet, too. “And Jacob and Natalie,” she went on — my brother Mike’s kids. “If I die, listen, I want you to share some things with all of them.”

I stopped her. “Let’s talk about this stuff when we get home,” I said. “When Desi takes a nap.”

“All right,” she said.

“You’re not going to die,” I told her.

“Sooner or later, I will.”

“Later.”

“Okay,” she said, tucking a wet Kleenex into her pocket and sitting up straight. “Later.”

By Saturday morning, Washtenaw County, where my parents live, was reporting its first COVID case.

The weekend passed in a rush. My brother Mike found a hospital bed for rent and arranged to have it delivered on Tuesday morning, right before my dad arrived. My mom and I recruited two people who were already members of the Care Team to come to the house in the weeks ahead as extra support — Sarah, a longtime close friend, and Donny, a high school pal.

Sarah lived with her boyfriend, and Donny with his girlfriend, who was Sarah’s twin sister — years before, I’d been the one to introduce them. All four agreed to begin quarantining, working from home, and staying put other than trips to the grocery store or to my parents’ house. That meant there would be eight people total in my parent’s “cell” of support, including Phil and Kaitlin. A tighter circle might have been better, but I trusted everyone to be smart and stay safe in order to keep my parents free from infection, and it was way more protection than we could have offered my dad had we left him at his nursing home.

After dinner on Sunday night, I put Desi to bed, then spent an hour with my mom posting updates on my dad’s GoFundMe page, hoping to ignite another round of donations. In the months since we’d launched the campaign, it had been moving to see the support from friends and family, and even the most distant of acquaintances, a few of whom had been especially generous. But now our window for raising funds was narrowing. Would anyone still prioritize supporting my dad once the virus had brought hardship everywhere?

“I want to tell you something,” my mom said. “This is very important.”

“All right.”

“If me or Dad gets sick and dies from this, I don’t want you or Mike or Peter to come home for a funeral. You can’t risk getting sick yourself.” She spoke pragmatically — not entirely devoid of emotion, but insulated from it. “It’s just a body,” she said. “You can do a memorial another time, when it’s safe.” In the moment, the idea of not attending her or my dad’s funeral seemed extreme — but of course, now, her concerns have proven to be prescient. Stories abound of funerals that fueled outbreaks of their own, with dire results. And those who have taken my mom’s advice have suffered, too: I have friends who still haven’t been able to gather with their families to mourn loved ones who died of COVID, months ago.

Over the baby monitor, I heard Desi cry out in his sleep. Sometimes, he’d fuss for a minute and fall back asleep, but these cries, I knew right away, were different — a kind of urgent wailing. Still, I thought I’d give him a few minutes to see if he could soothe himself.

I told my mom, “If you were sick, of course we’d want to come home and try to help.”

“They won’t let you into the hospital anyway. Please. You have to promise me.”

I told her that I wanted to talk it through with her, but that Desi was really upset and I had to go check on him. I hurried down to the basement and found him standing in his travel crib, his face soaked in tears. Usually, when he was crying and I picked him up, he quickly chilled out, but now he was nearly inconsolable. His whole body was shaking and wracked with sobs.

“What’s wrong, Desi?” I said, feeling helpless myself. “It’s okay, it’s okay, it’s okay.”

Some of the best advice I’d gotten early on was that when a baby cries, there’s usually a reason for it — they’re tired, hungry, or need a diaper change. Or perhaps they might be too hot or too cold. Rarely was there another explanation. I’d always found it helpful to have such a clear place to begin to troubleshoot. But these tears, I could tell, were different. It had been a stressful week, Desi’s daily routines were in tatters, and I imagined he’d absorbed some of the tension and heavy emotions he’d been surrounded by.

I pulled him into the bed with me, and he wailed against my chest. I tried singing to him, going straight to the big guns — “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” a song I’d sometimes reserved as a last resort when he was an infant and got lost on a crying jag.

Finally, finally, Desi’s breathing slowed. I slid my phone from my pocket and sent my mom a text; she read these on her iPad, which she always kept close at hand. ‘He’s OK now,’ I wrote. ‘But I need to stay with him. Sorry I might fall asleep.’ I felt bad ditching her mid-conversation, aware it wasn’t the only time I’d shut things down when she tried to broach vital topics. But right now, Desi needed me more than my mom did. And I needed him.

‘That’s OK,’ she wrote back. ‘Talk more tomorrow.’

‘Yeah tomorrow. Love you Mom.’

‘Love you.’

Some people appear in your life and bring you such goodness, you’re not sure what you could have done to deserve it, but you learn, eventually, just to accept their love and kindness with a sense of mystified gratitude. Sarah is that kind of angel.

I met her in 2004 — a tiny, brash Native American punk rocker who grew up in a remote Chippewa community in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula — and she quickly became one of my closest friends.

Over the years, Sarah had grown close with my parents, too. When my dad retired, he hired her as a kind of general assistant, working one day a week, to help him with various creative projects he hoped to dig into. They became genuine pals.

After my dad’s stroke, Sarah rushed to the hospital — she was the first of us to arrive — and in the months that followed, she became a vital lifeline for my whole family. I stayed in Michigan for a couple of months following the stroke but eventually had to return to LA, where Margaret was getting late into her pregnancy. Crucially, Sarah continued spending time with my dad a couple of days a week — at the hospital, then at his nursing home — making it possible for me to FaceTime with him on a regular basis.

Now, two years after he’d collapsed in the kitchen, my dad was due to move home again, in less than 24 hours. Monday afternoon, Sarah rolled by to help me prep the house for his arrival. I popped Desi into the backpack, and he kept to himself, clutching his beloved stuffed animal, Ellie the elephant, as Sarah and I cleared out the living room and transformed it into a new room for my dad. We hauled sofas out to the garage, shifted heavy bronze sculptures my mom had welded decades earlier from one end of the room to the other, and hung drapes to give my dad a measure of privacy, since the front windows of the house looked out on the street.

My dad was scheduled to come home around 10 the next morning, and to catch our flight to LA, Desi and I would have to head for the airport around 5 pm. On one hand, it pained me to know that our time together would be so limited, but I wasn’t sure I could extend the trip.

There were the small factors: When my dad came home, Kaitlin and Phil and their dogs would also be moving in, and the house would be crowded. And after a chaotic week, managing Desi all by myself, I was running out of juice. If I’d made the trip without him, it would’ve been a lot easier to hang in town for longer, but I was feeling burned out, and Desi seemed to also be at the end of his rope.

And then there were the larger factors, based on fear — rational fear — and a sense of self-preservation. I knew that the virus had been spreading, doubling its cases in three days.

To wait longer to fly back to LA meant increasing my chances of coming into contact with people who were infected. And I’m in a high-risk category myself: For 15 years, I’ve been taking a drug called Humira, a powerful immunosuppressant, to combat a rare form of arthritis. From what I understood, I might not be at a substantially higher risk for contracting COVID, but if infected, my body would struggle to fight it, and my chances for a severe outcome were hugely increased. I desperately didn’t want to get sick or to die, and felt eager to rejoin Margaret and cocoon myself safely at home.

Still, I thought of sticking around for a week or two and then renting a car and driving cross-country, back to LA, with Desi in tow. We could make it into a special kind of father-son road trip, I mused, stopping in national parks along the way, sleeping in the car or finding out-of-the-way spots to pop a tent. But Desi could barely tolerate a half-hour in his car seat. Driving 2,500 miles would be tough. Our best and safest bet was to fly back the next night, as originally planned.

Later, I put Desi down to sleep and began to pack up all of our stuff for the trip back to Cali; I wanted to minimize any time I’d have to spend packing the next day, when my dad was home with us. I’d moved most of my stuff out of the basement years before, but still there were remnants from earlier, wide-ranging chapters of my life — and every time I was home for a visit, I liked to bring a couple of random, forgotten things from the house back to LA with me: NFL pennants from my childhood, an old to-do list.

Far from home, the sight of these items, their weight in my hands, and even their smell, was endlessly transporting. I knew I might not be back in Michigan for many months, depending on how the pandemic shook out. (A year later, I still haven’t returned.) I thought about what it would be like if my parents died and the house was sold, and how much I’d miss it — the house I’d grown up in, the only house our family had ever lived in. Conceivably, this might be my last night in the house as I’d known it. What would it be like to be home again, on the far side of all of this, if my mom or my dad — or both of them — were no longer here?

I woke up Tuesday morning to voices upstairs, in the living room, right above me. Sarah had arrived early, by 8 am, to meet the delivery drivers from the medical supply company who’d brought my dad’s hospital bed. Over the roar of Desi’s white-noise machine, I could hear her directing them, and the sound of the bed’s tiny wheels running over the floorboards, as the floor creaked under its intense weight. Feeling oddly jittery, I took a few deep breaths to steady myself, and squeezed out the very last dollop of adrenaline from my reserve tank, like it was an empty tube of toothpaste. Then I pulled my clothes on, careful not to wake Desi, and slipped upstairs.

It was a bright, gorgeous day that felt more like April or May than mid-March. For an hour, Sarah and I finished getting the house ready, sweeping and mopping, washing dishes, and ordering a few more supplies for my dad — fitted sheets for his new bed, pillows and pillowcases, gauze pads, juice, juice thickeners. Desi woke up and we fed him breakfast and got him dressed. “Grandpa’s coming home soon!” I told him. “Want to see your grandpa?”

“Yes,” Desi nodded. He seemed to actually know who I was talking about.

Phil called me from in front of my dad’s nursing home. Though we hadn’t told them that he was most likely moving out for good, just to keep our options open, they seemed to be assuming as much; they had rounded up my dad’s clothes, CDs, boombox, and other personal effects — cards from friends, drawings from his grandchildren — and stuffed them all in a pair of garbage bags. At 10:30, an aide wheeled him out to the parking lot, set his bags of stuff next to him, and retreated inside.

Twenty minutes later, Dad, Kaitlin, and Phil pulled into the driveway in Kaitlin’s Nissan Cube, with Phil driving and my dad crammed into the front passenger seat, like a circus bear in a go-kart. I lifted Desi into my arms and hurried outside to greet them, my mom and Sarah trailing just behind us.

“Hey, Pops!” I cried, opening his door. “Welcome home, man!” I held Desi out so they were face to face. “Say, ‘Hi, Grandpa,’” I told Desi, forcing the action. “Say, ‘It’s good to see you.’” But Desi was shy, and he turned his head away, wriggling in my grasp. My dad, meanwhile, looked frazzled, slightly confused, and rough around the edges. It was clear he’d had a tough go of it ever since his nursing home had been on lockdown. But at last he turned his head creakily to the side, took a peek at us, and flashed a wry smile, looking happy to see us, and genuinely happy to be home.

Once my dad was settled in his wheelchair, he looked comfortable and at ease.

“Nice day, right?” I said.

“Nice day,” my dad repeated, with a smile.

“Nice day!” Desi chimed in.

Phil pushed my dad along the driveway, up a gentle wooden ramp, and through the front door, into the house, while I carried Desi in behind them.

We headed for the dining room, where my mom had laid out a spread of bagels, cream cheese, and veggies. The windows looked out over the backyard, alive with birds, and my mom’s garden, which seemed to have bloomed overnight. My dad joined us at the table, Sarah made him a bagel sandwich, and my dad dug in ravenously, while Desi sat with us in his own grown-up chair, with his own bagel on a plate, slouching like a teenager. His transformation over the course of one week was astounding. Even his face looked older, rounder, more thoughtful and mature.

My mom, Sarah, Kaitlin, and Phil found chairs and joined us. For months after my dad’s stroke, he’d been fed through a tube, and even though he’d been eating regular meals for a year now, and making visits home every week, it was always a little surprising to see him sitting there, feeding himself, just hanging out as though he’d never left. It seemed both utterly miraculous — given all that my dad had been through and the arrival of the pandemic — and at the same time strangely normal for all of us to be gathered around the table, sharing a meal.

Once we were done eating, Desi climbed to the floor to play with his toys, my mom and I joined him, and Sarah rolled my dad over beside us. My dad glowed, watching Desi build stacks of blocks and knock them down, run a little wooden train along its track, and roll around with Ellie and the gaggle of stuffed animals he’d collected from around the house.

At one point, Desi stood and teetered over to him, hugging my dad’s leg to keep balance, like it was the trunk of a tree. I tried to imagine what it would be like, one day, for Desi to have his own child, and to be able to watch that child laugh and play and learn to walk and start to talk, the same way my dad was watching Desi — a living creature, finding its own path, that had somehow splintered off of you.

I picked Desi up and balanced him in my dad’s lap. “I’m your daddy, and Grandpa is my daddy,” I reminded him. “Grandpa is your daddy’s daddy.” At first, Desi wasn’t too sure he wanted to be held, and looked dismayed and unsteady, as though afraid he’d get dropped. But my dad reached his left arm — his good arm — around him, and Desi relaxed in his perch.

“How about ‘Happy Birthday?’” I suggested. I explained that in a week, Desi would be 21 months, or one and three-quarters years old. Not the most widely celebrated of birthdays, perhaps, but I’d noticed that Desi loved hearing “Happy Birthday,” and I liked to sing it for him whenever the 24th day of the month drew near. I also knew it was a song my dad could sing with us, without needing help with the lyrics.

With Desi still in my dad’s lap, all of us burst into song, and an enormous, radiant smile spread across Desi’s face. He seemed tickled by the attention and happy to be hanging with his grandpa, who’d mostly just been the Man in the iPhone but now was here with him in real life.

We finished singing to him, and Desi laughed and clapped his hands together, and cried, “Yay!”

“Yay!” we cheered along with him. The room was bright with sunlight, like a Polaroid picture that had been overexposed. I felt myself glowing, surrounded by my mom, dad, and Desi, and the rest of my ad hoc family — Sarah and Kaitlin and Phil. I couldn’t imagine how heartbreaking it would have been not to have had the chance to see my dad at least one more time. But if we’d come all this way and had managed only these few minutes with my dad, it would’ve been worth it. At the same time, it crushed me to know that this could be the last of it. Why couldn’t the pandemic have come a few years later, when my dad was already gone?

By mid-afternoon, my dad was tired. Typically, at his nursing home, he took naps for an hour or two. We wheeled him into the living room — his new bedroom — and stretched him out in a reclining chair, where he closed his eyes and was quickly asleep. Desi was ready for a nap, too. I put him in his crib in the basement with Ellie, then hurried around the house, ticking off a long list of last-minute tasks — changing a lightbulb in the attic, loading a box of my parents’ old books — and then finished packing.

Sarah brought me things she’d found over the past few months, as she’d helped my mom pare down clutter from around the house, to send home with me to LA: old clothes, kids’ toys, a clay sculpture I’d made in seventh grade. Kaitlin joined in. Since she and Phil were moving into the basement, I realized, the more they could get me to pack out, the more space they’d have for their own stuff.

Finally, all of our bags were packed, all of Desi’s stuff collected and stowed, and Sarah helped me lug it all out to my mom’s van. In the front yard, she pointed out an abandoned wasp’s nest in the branches of a maple tree. “Those are the wasps that stung me last summer!” she said. “Can you get it down?”

The nest, about 20 feet up, was beige, the size of a bowling ball, and looked like it was made of papier-mâché. I found a fireplace log from a stack of wood by the garage, positioned myself right underneath, and heaved it up at the nest. Right height, but a foot wide. The log crashed down and I tried again. This time, I nudged the nest ever so slightly, but it was fastened tightly to its branch and absorbed the blow without flinching.

My next throw was way off, the one after that far worse. But on such a beautiful spring day, with Sarah’s gleeful company, it felt just right to be flinging a log in the air, again and again, however fruitlessly, in the same yard where I’d played as a kid, in front of the same house, surrounded by the same trees, as Sarah laughed and laughed and laughed.

Through the front window, I could see my dad, asleep in his chair. It was past 4 o’clock, and I knew it was irrational to spend the last hour I might ever have with him this way, pointlessly throwing a log into a tree. But that morning and early afternoon I’d already had the golden moments with him I’d been hoping for — and a part of me knew that whatever remaining time we spent together would only be difficult and sad. The longer I spent outside, the longer I could postpone the hardest part of my visit: having to say goodbye.

As he slept, my dad’s chest rose and fell with each deep breath he took. We were so lucky for him to have lived as long as he already had, I realized. A lot of my friends had lost their fathers in recent years, to cancer, heart attacks, strokes, even car accidents, at ages a decade or two younger than Dad was now. But how could anyone not feel greedy for another year with the ones they loved, then one more year, and just one more year after that?

Though we lived thousands of miles apart, my life was far richer with my dad around. It meant something to me to talk regularly and share stories with him of my stumbles and my successes. I especially wanted him to stick around to get to know Desi. And I wanted Desi to get to know my dad — to have his own memories of him, and not just learn about him from pictures and secondhand stories, as I had with my dad’s parents, who died before I was born. Every extra month, week, and day with my dad in the world is meaningful to me, to us. Because, despite the narrative that would soon emerge around COVID-19, the truth is, no one’s life is disposable — no matter how old, frail, or vulnerable they might be.

I saw that at last my dad was awake again. All of us went out to the back porch, including Banner, for what I knew would be my last 15 or 20 minutes with my mom and my dad for the foreseeable future.

It was a lovely spring afternoon, but as the sun dipped lower behind the spruce trees at the edge of the yard, a cold breeze blew. Kaitlin helped my dad pull on a hoodie. I hadn’t written any kind of grand speech, but I had a few ideas for how we might spend these last moments together: Among other things, I planned to present him with an Oscar.

My dad was a lifelong cinephile; he was the one who’d lit in me a love for movies and had sparked my interest in filmmaking. When I was a kid, he’d hung a movie screen in our living room. Once a month he borrowed a projector from a local church and got hold of closed-captioned versions of movies like Das Boot, The African Queen, North by Northwest, and Kurosawa’s Ran. Often, before the film, my dad showed us a couple of shorts — Laurel & Hardy; The Magnificent Six-and-a-Half — the way movie houses had done when he was a kid. We made popcorn, refilling our bowls between reels.

The Academy Awards became a special night for us each year. For months beforehand, we’d talk about who should win and who was likely to win. And for months afterward, we’d rehash our favorite speeches, and imagine the speeches our favorite actors and filmmakers might have made, if they hadn’t been robbed. No award loomed larger in Dad’s consciousness than an Oscar; it was bigger than Major League Baseball’s MVP trophy, bigger than a MacArthur “genius” grant, bigger than the Nobel Prize.

In the weeks before my visit to Michigan, I’d gone online and ordered a replica from an eBay store based in China and had it sent directly to my parents’ house, in hopes it would arrive in time for me to present it to him. Serendipitously, it had shown up earlier that day. Just to be safe, I’d cleaned the statue thoroughly with a couple of Clorox wipes.

On the back porch, I drew the Oscar from its case and handed it to my dad. “This is for you, Dad,” I told him. “Thank you for inspiring me.”

He set it on his left knee, peering at it, a little confused. A local trophy shop, I explained, had agreed to craft a nameplate for the base of the statue, once it felt safe for nonessential businesses to reopen. My dad lit up, briefly, and flashed me a smile and a thumbs-up. As I’d hoped, he didn’t seem to care that the award was fake; it signified his genuine achievements as a father. I launched into a lame and winding speech about how grateful I was that my dad had always responded to whatever interests I had as a kid by encouraging them.

The Oscar, I said, represented a fundamental lesson he’d instilled in me: that if something in the world excited and intrigued us, like filmmaking, we could find a way to get involved as creators, not just as fans. I reminded him of the time, at age 12, when I’d told him I’d wanted to make comic books, and he’d found an art class to enroll me in.

It wasn’t an awful sentiment to share, but I could see, even as the words tumbled out of my mouth, like teeth in a bad dream, how out of place and inadequate they were, in this moment. This was a time to go bigger, deeper, not just to thank him for signing me up for a one-day class where I’d learned to draw Marmaduke. Already, he’d lost focus on what I was saying, and was gazing with a sad look at Desi, in my lap, then out across the yard, where two squirrels battled over an acorn.

“Dad, listen,” I told him, reaching out to clasp his left hand, the one with feeling. “You’ve been the most amazing dad. I love you so much, and I appreciate all that you’ve ever done for us — Mom, me, Mike, and Peter. We’re so lucky we’ve had you in our lives, and had you as a dad.” My eyes were wet, and I could see that his eyes were moistening, too. “I’m going to try to be the kind of dad to Desi that you’ve been to me. To give him all of the opportunities that you’ve given me. And to show him what a wonderful world it can be.”

I hated that my words sounded so final, like I was afraid I’d never see him again, even if that was exactly the case. And truthfully, it wasn’t just his life I was frightened about, it was mine, too: COVID was already claiming the lives of people my age and younger.

I veered in a new direction. “Dad,” I said, “There’s this disease going around, and you know what, maybe you will get sick. But I know, if it happens, that you’ll be all right. You’ll make it through.” I felt like a football coach giving a locker room speech, down 24 points at the half — but at the same time, I believed every word that I said. I squeezed my dad’s hand and he squeezed mine back. “I love you,” I told him.

He looked me in the eye and nodded. “Love you.”

“And Desi loves you.”

My dad smiled and eyed him. He began to sing, in a quiet voice, “Desmond, Desmond; Desmond, Desmond.” Desi watched him, eyes wide. I felt twin balloons of sadness and joy rising in my chest.

“We should go,” said Kaitlin, who’d offered to drive me to the airport. “You’ll miss your flight.”

“Okay,” I said, checking the time on my phone. “Just a couple more minutes.” Quickly, I snapped a few selfies of Desi, my mom, my dad, and me. Sarah took a few more of us. Then, before I said goodbye and hurried out, I asked my dad to sing one more song: “Edelweiss,” from The Sound of Music. A couple of weeks before, over FaceTime, he’d really nailed it.

I pulled it up on YouTube, a version with words and music, so we could all sing along. My dad started out shaky at first, but soon found his footing:

Edelweiss, edelweiss, every morning you greet me.

Small and white, clean and bright, you look happy to meet me …

I’d been signing the words to my mom, and after a moment she joined in:

Blossom of snow, may you bloom and grow,

Bloom and grow forever …

Between the three of us, it might have been the most warbling, tuneless rendition of the song ever attempted, but it didn’t mean we sang with any less feeling. In the film The Sound of Music, Baron von Trapp, whose native Austria has fallen under siege by the Nazis, sings “Edelweiss” as both an elegy for the country he loves and as a subtle act of defiance against an occupying force. When my dad sang the last mournful lines of the song — then, and again, now, on the back porch — I felt like he was expressing what every one of us felt, across America and around the world, praying for salvation. I lifted my voice and sang along:

Edelweiss, edelweiss,

Bless my homeland forever …

In a week, everything had changed. The airport in Detroit was a grim, barren place, with a militarized vibe that reminded me of the weeks after 9/11. Police in midnight camo roamed with German shepherds so fierce that even Desi, doggie lover of all doggie lovers, edged away in fear. Was their presence, I wondered, meant to keep COVID at bay?

I wore pink rubber gloves, but it was no longer strange — many others wore gloves, too, while the TSA agents had added fierce-looking masks. I’d dressed Desi in a Detroit Tigers jacket that Sarah had uncovered deep in my dad’s closet — a jacket that had belonged to me when I was about 6. It was still a dozen sizes too big for him, making it perfect for this trip: the ends of the sleeves dangled uselessly a foot past his hands, which meant that he couldn’t touch anything.

We boarded the plane, and found that we were among maybe 30 passengers on the entire flight, with no one else in our row, or the rows in front of us or behind us. It may have been overkill, but after reading so much about how long the virus could live on surfaces, and knowing that Desi might very well lick the back of a seat or chew on an armrest, I cleaned the seats with Clorox wipes again, then spread an old spare sheet I’d dug out of the basement across our entire row, and a second sheet over the row in front of us. I wasn’t going to take any chances. (The irony is that neither Desi nor I had a mask; this was before the science had emerged around their efficacy.)

I glanced at the headlines on my phone: California had shut down all of its schools for the rest of the year. In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio was preparing to do the same. Four members of the Brooklyn Nets had tested positive for COVID, including Kevin Durant. And in Michigan, the number of cases had doubled since the day before, to 65.

Then I scrolled through the photos I’d taken over the course of the week — my mom and Desi playing; Desi, my parents, and me, on the back porch, just a couple hours before, the sun behind us, casting a rainbow lens flare. Already, my time in Michigan seemed like a dream. I felt as tired as I’d ever been, sleep-deprived and emotionally spent, and I stretched out across the row and closed my eyes, holding Desi as tightly to me as he was holding his furry stuffed elephant, breathing in step with him.

Past midnight, Michigan time, Desi and I reached LA. Margaret was there at the curb to collect us. In need of emotional release and relieved for the three of us to be reunited, I nearly cried when I saw her. It felt like we’d been gone for a year.

Margaret gathered Desi up in her arms and kissed his face and his head and his ears while I loaded all of our things into the trunk of her Jeep. The curbside, I noticed, was littered with hundreds of pairs of rubber gloves, tossed to the ground by passengers upon pickup, a rainbow-colored pastiche. It made sense, I supposed: No one wanted to bring dirty gloves into their loved ones’ cars.

For a moment I wavered, as I tugged off my own gloves and climbed behind the wheel so Margaret could ride in back with Desi, unsure which was stronger: my instinct not to risk bringing the virus into the car or my impulse never to litter. Finally, I zagged back inside the terminal to stash my used gloves in the garbage — one small, righteous deed after a week of overwhelming, confusing, and uncertain ones. Then I hopped back in the Jeep and we headed for home.

Five days later, my dad’s nursing home sent out a letter to every resident’s family. Since my dad hadn’t officially moved out yet — he was home, technically, only on a 17-day therapeutic leave — we were still on their mailing list. The letter began: “We want to inform you that we have received confirmation that an individual at [our nursing home] has been diagnosed with COVID-19 …”

In the days that followed, new cases appeared. Quickly, it became clear just how lucky we were to get him home, and just how narrowly he may have escaped. A Michigan government website tallied at least 50 COVID cases at his nursing home. In the months that followed, around the country, some nursing homes would, true to the headlines, become death traps, with bodies stacked in the laundry room, in utility closets, or in sheds in the yard. A veterans home in Massachusetts clocked 76 deaths. A retirement home in South Carolina had 59. Still others have emerged largely unscathed.

In his first months at home, my dad thrived. Desi and I liked to FaceTime with him in the morning. We’d sing songs and make faces at each other, and sometimes I’d read kids’ books to both of them, my dad chiming in here and there with a hoot or a chuckle. Sometimes I’d run to the other room to pee or to grab Desi a snack, and I’d leave them alone to bond with each other. When I’d come back, I’d try not to interrupt, but instead just watch from the doorway: the two of them communicating in their own slapdash, improvised language, a mix of simple words, grunts, squeaks, and laughter, like alien species across a vast cosmos.

Whatever happened, I knew it had been worth it to find a way to get my dad to safety. In the best case, we’d be home to visit him again before long, as the virus became contained. Worst case, my dad would have spent his final days in the house where he’d lived more than half his life, the house where he’d raised his family, with my mom and Banner close at his side. I knew he was taking joy, every day, in being there with them.

Things got harder mid-summer, when Phil and Kaitlin moved out. My brother Mike came home for a few weeks to help, but he, too, had his own family who needed him. A series of other caregivers came into our lives, some heroic, others harrowingly cavalier in their approach to COVID safety. But our options were limited to what we could afford, particularly as the pandemic stretched from weeks to months and beyond. My gravest fear, knowing how much time my mom spent at my dad’s side, was that not only would he get infected, but that she would, too. By bringing him home, and cycling caregivers through the house every day, we were putting them both at enormous risk.

Before Christmas, just as the first vaccine vials began to be distributed, my dad’s most capable and reliable caregiver fell sick with what seemed like COVID symptoms; his partner worked as a hospital nurse and was also sick. Only after a terrifying week did we learn that both had tested negative.

In January, a different caregiver’s live-in girlfriend tested positive for COVID. He had spent three days at my parents’ house the previous week. We knew that if the caregiver was infected, my dad would likely be, too. It was painful and perverse to imagine that my parents might have evaded the disease for so long, only to get sick when they were weeks away from getting vaccinated.

Ultimately, the caregiver never tested positive, and neither my dad nor my mom got sick. We have been extremely lucky. Friends of mine who perfected safer protocols, who lived in parts of the country with lower infection rates — who did everything “right” — still lost their parents to COVID. Reasonably, they are heartsick and furious at the lack of national leadership, and at the way partisan politics eroded trust in basic science and deepened the virus’s spread.

I knew these friends’ parents. Their lives were in no way expendable, and their loss is felt every hour of every day.

A few weeks ago, my mom wheeled my dad into Michigan Stadium, the state’s largest vaccination site, for his first shot. The same stadium that had become a way for me to quantify the country’s escalating death toll, as I multiplied its capacity by two, then three, then four, then five. It felt especially meaningful to me for the stadium to now signify life, hope, and renewal. My mom texted me a picture of my dad getting jabbed in the arm while flashing a thumbs-up. I was overcome, flooded with tears of relief.

Last week, a friend drove my mom to downtown Detroit, where she got her second shot, in the parking garage of the TCF Center, where votes were counted — and challenged — after the 2020 presidential election. In the coming months, I hope to get a shot or two myself, and then, eventually, to visit home again for the first time since the pandemic began, bringing Desi with me. Last March, a year ago, he was a baby who had just learned to walk. Now he’s a little boy who climbs mountains by my side.

For us, even the bleakest challenges of the past year have been redeemed by our time in nature. In the evenings, every day, an hour before sunset, Desi and I hike up Elephant Hill, a lookout point behind our house in Northeast LA. The place is a haven for Jeeps, ATVs, and motorcycles, and the dirt road that winds its way to the top is strewn with mounds of trash, but is heavenly nonetheless: towering yellow wildflowers on either side, and a dazzling three-sixty view from the summit, stretching from downtown L.A. to the snow-capped San Gabriel Mountains. Down the backside of Elephant Hill, Desi and I have our “picnic spot” where we hang out, wrestle, read books, eat snacks, look for birds and rabbits and butterflies, and watch the sun go down. From up here, the world looks green, fertile, both idyllic and foreboding.

Often, as the sun slips out of sight, and the weeds around us blow this way and that, Desi sits quietly in my lap, staring across the valley at the distant, jagged peaks. I wonder if later in life he’ll remember these moments, the way I remember walking with my parents through the patch of woods behind our house when I was his age.

My quarantine life, like so many other people’s, is a strange, formless, timeless thousand-mile stroll through a desert, laced with danger, boredom, and beauty. I don’t know how the pandemic will play out, if new variants or decreased vigilance will threaten the progress we’re making with vaccines; I don’t know how much longer it will be until I see my parents — Desi’s grandparents — in person again. But for now, Desi and I have this lush landscape, a hawk’s caw, a rabbit’s scamper, a helicopter droning over the city. I have my parents, my wife, and my friends.

For now, I have hope.

For now, we have each other.

Davy Rothbart is the creator of Found magazine, a filmmaker, contributor to This American Life, and author of My Heart Is An Idiot.