Circa 1912. The house was built by Frank B. Wiborg, who enlisted architect Grosvenor Atterbury, the designer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American wing. Right, the tower, which was destroyed in the 1938 hurricane; behind it, the garage and servants’ quarters, which later became the Pink House. Photo: © Estate of Honoria Murphy Donnelly/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

At the beginning of the last century, a shy 16-year-old named Gerald Murphy met a beautiful 20-year-old, Sara Wiborg, at a party in East Hampton, where the Golden Age’s millionaires were just beginning to erect mansions along the white sands. Gerald’s parents had a house in Southampton, but Sara’s father, Frank B. Wiborg—who’d made his fortune selling printing ink in Cincinnati—built the Dunes, the largest house in East Hampton at the time, with 30 rooms and grounds that included Italianate sunken gardens, stables, a working dairy, and separate servants’ quarters. Wiborg was a genuine land baron, and his East Hampton holdings, according to Calvin Tomkins’s Living Well Is the Best Revenge, encompassed 600 acres—a mind-blowing parcel by any measure, and one that would be worth, by conservative estimates, at least $1 billion today. But by the time the Dunes was finished in 1910, he was down to the mere 80 acres pictured here—a parcel that’s now covered by multimillion-dollar mansions, golf courses and other markers of Hamptons status crammed onto some of the world’s most valuable real estate.

Gerald and Sara married in 1915, eleven years after that party, and became the kind of couple that seems invented for fiction: worldly, artistic, bohemian, glamorous. Years later, their friend F. Scott Fitzgerald would use them as the model for Dick and Nicole Driver in Tender Is the Night. They spent the twenties living on the Riviera with their three children. They bought a house in Cap d’Antibes, remodeled it, and named it Villa America. Gerald painted and exhibited in Paris at the Salon des Independents in 1925, and had a posthumous retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1974, and the couple entertained their luminary friends: Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Jean Cocteau, Cole Porter. But in 1933, when Europe began to roil and their son Patrick was diagnosed with tuberculosis, they came back to the U.S. and Gerald ran the leather-goods company Mark Cross, which his father had founded.

Though it seemed golden-hued, the Murphys’ life was far from perfect. Both died before adulthood: Baoth, the elder, in 1935, from meningitis, then Patrick, two years later, to tuberculosis. After their deaths, Gerald said to Fitzgerald, “Only the invented parts of our life had any meaning.” Their daughter, Honoria, became their sole heir.

The legendary 600 acres had already shrunk by 1910, and when Gerald and Sara moved there in the thirties, they began to sell off parcels. The enormous, financially burdensome Dunes was demolished in 1941 when the Murphys couldn’t find a buyer or renter. Sara and Gerald took up residence in the dairy barn, renovated it and named it Swan Cove. “I remember home movies where Grandma and Grandpa were bundled up in coats and Dos Passos and Bob Benchley were popping out of the big urns at Swan Cove,” recalls their granddaughter Laura Donnelly. In 1959, Sara and Gerald built a house they called the Little Hut next to the servants’ quarters and garage, which Honoria renovated and dubbed the Pink House; it was where her children spent their summers.

“I remember seeing the Léger in the living room,” Donnelly says of the many treasures on the walls of the Little Hut. There were other, more down-to-earth charms, like the antique hand-carved farm tools that Gerald collected and displayed, or the mirror that he framed with rope and hung in the front hallway.Gerald died in the Little Hut in 1964, courtly to the last; his final words to his wife and daughter were “Smelling salts for the ladies.” Today, the Murphy legacy lives on with his grandchildren, who still own the last remnants of the great Wiborg property—down to the tantalizingly overflowing boxes waiting in the old estate’s garage. Next: An Aerial View of the Wiborg Estate

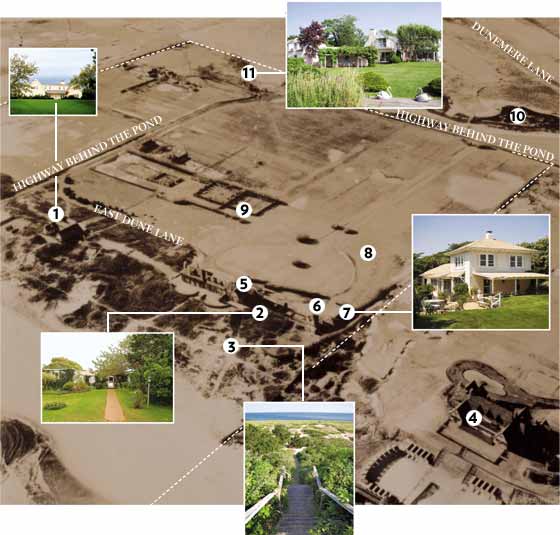

The Wiborg Estate

In an aerial view from the twenties, when Wiborg’s original 600 acres had been whittled down to a mere 80. The property’s boundaries are marked in white.

(1.) Olga Wiborg’s house

Sara’s sister Olga first lived here; later, Lee Radziwill bought the property. It now belongs to financier Thomas H. Lee.

(2.) Little Hut

The only house the Murphys built from the ground up, it was completed in 1959. A Fernand Léger hung in the living room alongside Gerald’s collection of old wooden farm tools. It’s now owned by the Hill family.

(3.) Beach Path

Gerald took this path to Wiborg Beach to do his daily laps.

(4.) The Maidstone Club

The clubhouse pictured, which still stands today, was built in 1922. It replaced the club’s first headquarters, which had been much farther inland but burned down.

(5.) The Dunes

Once the largest house in the Hamptons, it was torn down in 1941 when the Murphys couldn’t rent or sell it.

(6.) The Tower

Used for the estate’s laundry, it was destroyed in the 1938 hurricane. Its foundation became the patio of the Pink House, right.

(7.) The Pink House

The Murphys’ daughter, Honoria, renovated the servants’ quarters and painted the stucco exteriorpink (now faded to a pastel). It is now owned by her three children: Laura, John, and Sherman Donnelly.

(8.) The Last Acre

The Murphy heirs sold a single acre plot to the Peconic Land Trust a few years ago, “with the intention of eliminating building rights,” says Laura Donnelly. It was then sold to Maidstone, which incorporated it into the golf course.

(9.) Sunken Gardens

The three Wiborg sisters rode their horses in the fields surrounding the extensive gardens that were modeled on Italian designs.

(10.) Hook Pond

(11.) Swan Cove

Gerald and Sara converted the Wiborg estate’s dairy barn into their summer house. It now belongs to the DeLiagre family. Next: A Photo Album of the Jazz Age Hamptons

Photo Album