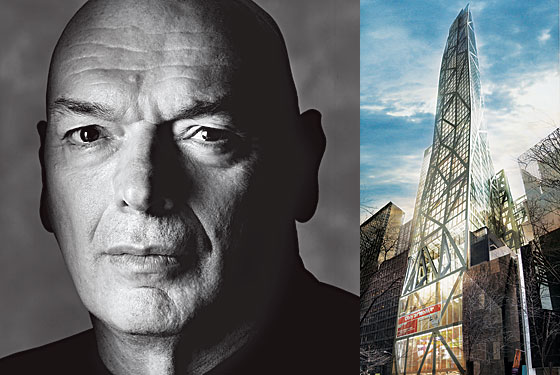

Just off Sixth Avenue, squeezed in next to the Museum of Modern Art, is a sliver of fallow ground just big enough to accommodate a convenience store or a few brownstones—or, come to think of it, a tower as tall as the Empire State Building. Skyscrapers have gotten skinnier, and three years ago, the architect Jean Nouvel designed an exhilarating mirage for this site, a slender, 1,250-foot ballerina of a building, corseted in steel beams and perpetually en pointe. The project—Tower Verre, he calls it—seemed like too flamboyant a fantasy for a cautious metropolis, and indeed the City Council approved only a stunted version, which demands a new design.

“We have to restudy it, without starting from zero,” Nouvel says. “I don’t think we have to revisit the essentials of the structure.” It may still be a twisting, sloping needle, enfolding new MoMA galleries in its base and rising to apartments with great glass walls slashed by tilting columns. Only now it can reach no higher than 1,050 feet, a toddler’s height taller than the Chrysler Building and 200 feet shorter than the Empire State. About this, Nouvel is by turns philosophical and resentful. “The past is the past,” he says with a shrug. A few minutes later comes the zinger: “What is surprising is that Manhattan should be afraid of verticality.”

Nouvel the person does not have the precise flash and lean grace of his architecture. He is a large, slow-moving man with a melancholy mien, who always seems to be in need of a nap. Conversing in English prods him into alertness, but in French, he relaxes gratefully, letting his mini-lectures trail off in baritonal mumbles. When I meet him at 100 Eleventh Avenue, the spangled new condominium he’s designed, his black-leather-on-black outfit camouflages him against the polished inky granite of the lobby, so that his great bald dome seems to hover in midair. In the white apartments he looms like a shuffling shadow. Like one of his buildings, he manages to appear conspicuous yet at home.

“I am someone who tries to be a contextual architect,” he says. “I’m always trying to figure out how to reveal the beauty of the surroundings.” That’s a provocative statement, given that he gift-wrapped Copenhagen’s new concert hall in brilliant blue fabric, made Minneapolis’s Guthrie Theater levitate over the Mississippi waterfront, and transformed the low Barcelona skyline with a giant, glowing, tessellated phallus. Yet, glitzy as Barcelona’s Agbar Tower is, it does belong in the brightly hued, ostentatiously sexualized Spain of Pedro Almodóvar, and it does harmonize with the city’s extravagant landmarks: the colored fountains atop Montjuïc, and the corncob towers of Antoni Gaudí’s Sagrada Família. Nouvel has a talent for finding contexts to embrace his idiosyncrasies, and then making the results seem inevitable. “All my work is a search for what I call the missing piece of the puzzle,” he says, deftly implying that Barcelona wasn’t complete until it received his multicolored lingam, and that midtown craves his Tower Verre.

The 53rd Street skyscraper will adapt to its new height, but Nouvel insists that it must stick to the original brief: “to complete this cultural neighborhood and to complete MoMA—with a hotel and residences, yes, but it’s mostly a cultural object. It has to keep the same ambition.” Some observers have wondered whether the design’s decapitation, combined with the financing drought of the past two years, would force the development company, Hines, to scrap the whole idea. But Robert Knakal, a commercial-real-estate investment-sales broker, suggests that the warming market makes it fairly likely to be built. (A Hines spokesperson will say only that “we continue to work on the project.”)

In Nouvel’s view, Tower Verre is not just another commercial high-rise but an emblem of its moment, a testament to the city’s self-renewing vitality, and a crown on its mutable skyline. “We’re in midtown,” he says. “A place where we have to make a real skyscraper. It emerges from the skyline and you say: Okay! That’s where MoMA is! It testifies to what the skyscraper is at the beginning of this century. It’s not a copy of what the twentieth century did. It brings new forms of expression. The corsetlike structure on the perimeter of the building, the way it follows setback rules with a dynamic form of ascent that’s not the habitual stepwise manner, a structure that erases the distinction between outdoors and in—these things tie this building to the culture of these last few years.”

Nouvel made his New York debut nearly a decade ago, breaching Soho with uncharacteristic modesty. With its industrial gray steel and splashes of red and blue glass, the condominium at 40 Mercer Street inflected the neighborhood’s industrial past with Sex and the City glamour. Then came 100 Eleventh, a boom-time straggler that puts to shame the past decade’s crop of generic tinseled boxes. If in Soho, Nouvel had to grapple with a powerful urban personality, in West Chelsea he can help shape an area that still hasn’t quite jelled. A wall of slightly tinted windows, angled like mosaic tiles, sweeps around Manhattan’s cocked hip. From the outside, the variously coated and tilted panes deconstruct the sunset, give the curving façade a glittering, disco-ball effect. Crescent-shaped rooms get wraparound views, segmented like a jigsaw puzzle by irregularly sized windows that fit together, with no solid wall in between. It’s as if the builders had removed the masonry, chunk by chunk, until there was nothing left but glass. A fragmented, distorted reflection of the façade enlivens the curving white glass surfaces of Frank Gehry’s IAC headquarters across the street, turning that end of the block into a friendly fun-house game between architectural superstars. “It’s an interference—an intentional interference—that makes me happy,” Nouvel says. “And it makes Frank happy, too, from what he’s told me.”

But 100 Eleventh Avenue is Janus-faced, simultaneously opening westward to the evening sun (and pummeling rains) and turning a stern black profile eastward toward the city. A scattering of punched windows breaks up that wall’s solidity. The arrangement looks irregular and uneven, and the reason for the randomness becomes apparent only from inside. Each opening composes a specific urban view, like a framed photo: the

If Nouvel was hoping that 40 Mercer and 100 Eleventh would prepare the way for 53 West 53rd Street, he was wrong. From the moment it was first proposed, the skyscraper tapped a gusher of outrage. Neighbors felt besieged by the coalition of a globe-trotting architect, the Houston-based developer, and an expansionist MoMA, which sold the lot to Hines partly in exchange for space in the new building. Although it’s only tangentially the museum’s project, people tend to think of it as the “MoMA tower,” and the website no2moma.com includes an animation tracking its shadow across Central Park. The group behind that site, the Coalition for Responsible Midtown Development, has teamed with the local block association in a suit to annul the city’s approval.

Much of this furor is rooted in the desire to avoid noise and disruption on a street where MoMA only recently spent years under construction. Some of it probably also represents the primal horror of enormousness that persists even in midtown Manhattan, a revulsion expressed as a law of human nature by the title character of W. G. Sebald’s 2001 novel Austerlitz: “No one in his right mind could truthfully say that he liked a vast edifice … At the most we gaze at it in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed from the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.” But if you’re standing on the sidewalk looking up, it hardly matters how high the spires reach; an ant doesn’t distinguish between a five-foot human and one who’s six-foot-four.

The most reasoned and nuanced opponent is Ada Louise Huxtable, the city’s senior architecture critic, who at 89 still contributes reviews to TheWall Street Journal. Huxtable worries about “zoning creep”—the gradual dilution of the rules that confine high-rises to the avenues and keep the side streets low. “It is the wrong building in the wrong place,” she writes in an e-mail message. “I have watched the town houses and brownstones on 53rd Street go down like dominoes over the years—it was one of the loveliest streets in the city—but the fact that they are gone does not make this building right. What I see is an enormous real-estate deal with cultural window dressing, a case history of how the zoning rules can be used to do something they were never meant to encourage.”

To Nouvel, the impulse to reject his 53rd Street tower is a symptom of an urban death wish. “As in all cities, there are conservative associations that don’t want a construction site near them and don’t want anything to happen,” he says. That’s the classic response of a spurned avant-gardiste: to accuse critics of reactionary sentiments. But Nouvel also sees the battle of Tower Verre as part of a larger struggle to define New York: Is it a more or less finished city, a museum of itself that must place a premium on preservation? Or should it still participate in the rude business of progress?

For him, cutting his building down to size was a way of protecting the skyline and stifling the manic ambition that created it in the first place. “Embalming the city—that means gradually turning it into nothing more than a tourist destination,” Nouvel says. “Paris runs the same risk.” (Nouvel lives in Paris, and although he has built several high-profile projects there, he also designed two separate skyscrapers that were approved, then shelved.) “The most extraordinary cities create energy as they form themselves, and that energy and complexity are qualities you can’t abandon. Our responsibility is to bear witness to our era. A city’s identity is not just something you preserve. It’s something you create too.”

Nouvel speaks clearly about the kind of city he abhors; less so about how a modern megalopolis like New York should continue to develop—aside from building his designs. In 2005, he wrote the “Louisiana Manifesto,” which reads like a French philosopher-architect’s cri de coeur as imagined by Stephen Colbert: “Architecture has to be impregnated and to impregnate, to be impressionable and impress, to absorb and emit … Let us denounce automatic architecture, the architecture of our serial production systems! Let us attack it! Engulf it! This soulless architecture crying out to be contradicted.”

This torrent of verbiage disguises an analytical approach based on a pair of solid principles. First, any new building on the skyline ought to start a conversation between the existing city and the fresh addition, each nudging and coaxing and shaping the other, in the way a family rebalances around each new child. Tower Verre, for example, tapers to an old-fashioned peak, lightening a skyline squared off with half a century’s worth of blocky modernist cubes. Second, a new monument shouldn’t aspire to timelessness, but speak with vivid specificity of an instant in a city’s life. You can grasp what this means at 100 Eleventh, which is already a poignant relic, containing within it a memory of the era that made it possible, the heat of the present, and the specter of a glorious obsolescence. Standing outside the building, Nouvel shouts over the traffic and imagines the impression his creation might make on future drivers. As they speed by, fleetingly dazzled by a reflection from the façade’s mosaic of windows, he suggests, they will glance up through the windshield and think of 2010. The building will date itself, Nouvel agrees, and that is the finest gift an architect can bequeath to posterity: “It will show what moved us in that period, which is to say … now.”

See Also:

Justin Davidon on Why the City Should Let Jean Nouvel Build His Tower