Frank Gehry’s New York looks so vivid in miniature, a parallel city of masterpieces in plastic, cardboard, and painted foam. Let’s start our fantasy tour at the vantage point of Brooklyn Heights. That’s the Guggenheim’s downtown branch across the East River, on the Manhattan side, rearing out of the spume, whipping together water, sky, and steel. Sheets of swirling metal enfold galleries that seem to levitate over the piers, which form a public esplanade. In winter, you can tour the outdoor sculptures on ice skates. “Commerce surrounds her with her surf,” wrote Herman Melville of Manhattan, and the new building stirs the old excitement of a maritime New York, a city at the nation’s edge. Gehry’s money-bright museum stands at the confluence of capital, art, and tide.

Now let’s head uptown to the New York Times tower, a glass Niagara that churns and foams as it hits the ground. The wrapping billows to enclose a sunny, sexy atrium. The crumply exterior alludes to the publication’s paperbound history; its motion intimates a more fluid future; and the image of a tower trying to escape from itself reminds journalists that news takes place everywhere but in a reporter’s cubicle.

Finally, we head over to Brooklyn for the village-within-a-city called Atlantic Yards. An office tower rises to within one foot of the Williamsburg Savings Bank’s height, nodding to an icon of the Brooklyn skyline even as it reshapes that horizon with panache. The building resembles a statuesque diva, its sweeping skirts of glass and baroque metallic robe parting to reveal a dramatic atrium. Or, in another version, it consists of blocks piled high, nudged out of alignment and twisted around a structural core. At the tower’s feet sits an oval arena clad in rippling blue steel, and fifteen more buildings of assorted sizes and degrees of Gehry-ness march off in double file.

It’s a lovely daydream, this jaunt through a more architecturally brazen town than the one we actually inhabit. New York and Frank Owen Gehry should have made a perfect match. What better way to express the city’s exceptionalism than through architecture of overweening flamboyance?

Well, the East River Guggenheim doesn’t exist, and the Times makes its headquarters in a sober tower by Renzo Piano, caged in ceramic rods. Atlantic Yards evolved from an exciting ideal to a battleground for the soul of Brooklyn to a sinkhole of betrayal and mediocrity. Over the years, New York has been tantalized by Gehry projects, tossing away the best and keeping a paltry scattering of seed pearls: a corporate cafeteria in the Condé Nast Building, a boutique interior for Issey Miyake, the handsome but hardly epochal white-glass headquarters of IAC in Chelsea, and the Beekman Tower, a conventional high-rise rental in a flowing metal toga. Perhaps, if all goes better than expected, a nonprofit organization will drum up the money to build a playground he designed for Battery Park.

The map is dotted with Gehry coulda-beens. At ground zero, his home for the Joyce Theater has less and less chance of materializing. The Theater for a New Audience in Brooklyn, on which Gehry was to collaborate with Hugh Hardy, will instead be an all-Hardy affair (if it gets built at all). The Astor Place hotel he conjured for Ian Schrager is a dim memory.

By far the worst disappointment is Atlantic Yards. For years, opponents of the project, appalled by its scale and hostile to the developer Bruce Ratner, warned that Gehry was providing a fig leaf of avant-gardism to cover a real-estate magnate’s obscene greed. A project so debased couldn’t generate good architecture, they insisted. In 2007, the author Jonathan Lethem wrote an open letter pleading with Gehry to walk away. “These buildings,” he wrote, “have emerged pre-botched by compromise, swollen with expediency and profit-seeking.”

But for Gehry, Atlantic Yards represented an irresistible chance to do for an urban district what he had done for the museum and the concert hall: establish a new archetype. In his desire to believe, he made the mistake of trusting Bruce Ratner, or at any rate got himself so enmeshed that the developer’s company, Forest City Ratner, once represented 35 percent of Gehry’s business. When I visited the architect at his Los Angeles studio in April, he described Ratner as “a decent guy. He goes to concerts, buys art, can quote from Joyce. He wants an architectural legacy.” Gehry insisted to me that he has a nose for cynics, and that Ratner wasn’t one. “We turn work down if it’s not real, or if people have a warped image of what I do. This stuff works only when there’s a true partnership between client and architect. If they’re trying to build a monster on the landscape and they’re just using me to get more approvals, I usually opt out.”

A few weeks after that conversation, Ratner scrapped six years’ worth of design work. Pleading financial straits, he fired Gehry from the whole project and replaced his arena design with a graceless Cow Palace knockoff by the journeyman stadium-builder Ellerbe Becket. To judge by early renderings, the new offering isn’t simply inferior; it’s insultingly bad. Yet Gehry has served Ratner well. His involvement helped strong-arm the city and the state into delivering tax breaks, permits, and the power to evict holdouts. It helped beat back opposition, secure $400 million in naming rights from Barclays, and win over the architectural press. Ratner didn’t just toss Gehry into the drink; he betrayed the city, blighted a neighborhood he promised to transform, validated his opponents, and blew a colossal opportunity to bring great architecture to a city that badly needs it.

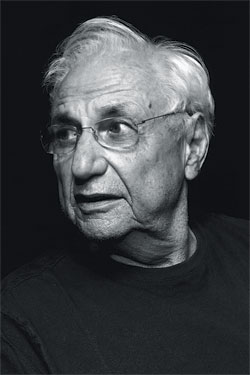

On a Saturday morning in Los Angeles, a handful of young designers huddle in Gehry’s vast studio, a former BMW operations center near Marina Del Rey. Even on a weekday, the warehouse would feel roomy: The staff is about half the size it was a year ago. “I haven’t felt abandoned by New York,” Gehry says, and it’s true that his troubles have come from all over. He turned 80 in February, and the world paid tribute, but it’s still been a tough twelve months. In November, a major project in Brighton, England, was canceled. A few days later, the architect’s daughter Leslie Gehry Brenner died of uterine cancer at 54. The following month, Atlantic Yards and a downtown–Los Angeles redevelopment plan both foundered. Within a year, the firm lost nearly 100 employees. Gehry has even fired Gehry: After spending years designing a new house for himself and his wife, Berta, in Venice, California, he recently dropped the plan. What’s left of the firm has plenty of work to do, notably on a sprawling Guggenheim Museum branch in Abu Dhabi. But the boss has been thinking about what Gehry Partners, LLP, might look like without Frank Gehry.

He ambles distractedly about the studio in khakis and a stained T-shirt, while several designers glue together a scale model of a modest New Orleans house commissioned by Brad Pitt’s foundation. The room is strewn with models, ranging from basic assemblages of colored blocks to elaborately finished miniatures. On one shelf, a model of a tower engages in a cartoon striptease, twisting, stretching, and trying on an assortment of skins.

His teams work in three dimensions from the first. “The models represent the essence of the functional requirements,” Gehry says, in his soporific rumble. “They have to be truthful. They can’t tell a lie. You can’t do fluffy stuff. Sometimes some designer crumples a piece of paper into a model. They think they’re pleasing me, but it just pisses me off.”

At the Guggenheim retrospective in 2001, that profusion of miniatures crackled along Frank Lloyd Wright’s ramp in a chain of linked epiphanies. The heart of the show was the Peter Lewis House, its forms like vital organs that kept morphing over a decade until it had traveled so far into the realm of the imagination that it was never built. Or most of it wasn’t: Gehry eventually recycled an entry hall shaped like a horse’s skull into a conference center for a German bank. Sometimes, it’s the most straitlaced clients who want the wildest designs.

The Guggenheim exhibit highlighted the museum’s doomed East River expansion and the fantastically successful Bilbao branch. Bilbao is Gehry’s touchstone: In conversation, he circles back to the titanium cloud every few minutes, proudly describing the transformative effect his museum has had on the Basque city, and taking a grumpy swipe at the pack of new museums it unleashed. He rejects the standard story line of his career: that the project rocketed him to worldwide fame at 68, and brought him a cascade of opulent commissions.

“You’re buying into the fairy tale,” he protests. “Bilbao opened in 1997. It was only ten years later that I was asked to do another museum. A lot of other people got work because of Bilbao.” The “Bilbao effect” refers to the power of a flamboyant new cultural building to invigorate the local economy. But the phrase could also describe his paradoxical challenge: How do you satisfy clients who come for similar explosions of innovation? How does Frank Gehry compete with “Frank Gehry”?

The problem is encapsulated in a pair of leechlike terms: “icon” and “starchitecture.” The first refers to a building that bewitches the eye and forces the environment to adjust. Used approvingly, it suggests a work so powerful that it will never be taken for granted. Applied pejoratively, it implies a lunge for momentary wisps of attention, offering little in return.

“Starchitecture” is a glib neologism that reduces hard-won reputations and decadelong undertakings to little dabs of glitz. Gehry can hardly bring himself to utter the word, but the mere mention triggers a tirade revealing deep wells of grandiosity and resentment. “It suggests an egomaniac trying to flaunt his wares at the expense of the public. It’s an opportunistic journalistic trick. There’s so much bad stuff being built that people don’t address, so they fasten on the half of one percent that gets into uncharted territory for humanistic and idealistic reasons. There is ego involved; everyone has to have that, or they don’t do much. But architecture has always been a very idealistic profession. It’s about making the world a better place, and it works over the generations, because people go on vacation and they look for it. When I go to Bilbao, they want to touch me. If I were an egomaniac, I’d just move there.”

More than any architect since Frank Lloyd Wright, Gehry exerts a hold over the popular imagination. He has played himself in The Simpsons. Walt Disney Concert Hall, his Los Angeles masterpiece, appears on guidebook covers and in car commercials (“by the way, we don’t get royalties for that!”)—and on the History Channel’s hit parade of Engineering Disasters. The glare from the shiny metal roof heated up nearby apartments and dazzled motorists, a pretty innocuous goof. “They fixed it for $40,000,” Gehry says crossly. “I just sent some people over there with steel wool.”

It’s hard to avoid the impression that Gehry’s failures offer him a measure of comfort, a way to preserve his sense of outsiderdom. He was born Frank Goldberg, the son of a demoralized Toronto businessman who moved with the family to Los Angeles in 1947. Poor, Jewish, and new in town, the teenager was triply an outsider, and though he eventually got rich, changed his name, and became America’s preeminent architect, he still carries a brittle sense of exclusion. In Conversations With Frank Gehry, a book of interviews conducted by Barbara Isenberg, the architect lovingly recounts his humiliations: the conclave of L.A. artists that excluded him from a meeting about the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art; the Disney-family lawyer who vowed that no Gehry building would bear Walt’s name; a catastrophic evening when Dorothy Chandler declared that he would never build a concert hall, a waitress spilled buttered vegetables on his lap, and a dinner guest referred to a house he had designed as “that piece of shit.” He savors these indignities, as if they confirm a suspicion that the snobs are right to reject him. “Each project I suffer like I’m starting over again in life,” he says. “There’s a lot of healthy insecurity that fuels this stuff.”

The mention of the word “starchitect” triggers a tirade. “It suggests an egomaniac trying to flaunt his wares at the expense of the public.”

It takes a lot of love to overcome those doubts, and when he’s not getting enough of it, the architect can balk. In 2000, Gehry participated in a competition to design the Times tower, a joint development of the newspaper company and … Forest City Ratner. The Times’ then–architecture critic, Herbert Muschamp, wrote that Gehry withdrew his proposal before the competition had run its course. Gehry tells a different story: “They gave us the job. Then we were put in a room of construction guys from Forest City Ratner who said I had to be in New York for a meeting every Monday at 2 p.m. I said I couldn’t. I left that meeting and called the Times and pulled out. I sent them back their check.”

Besides being the world’s most laureled architect, Gehry has become the most detested. His critics are many and varied. John Silber, the former Boston University president and author of Architecture of the Absurd: How “Genius” Disfigured a Practical Art, directs a water cannon of contempt at the Stata Center at MIT, attacking it as the triumph of caprice over rationality. To him, leaning walls, glittery wrappings, and curvy surfaces are unjustifiably expensive, arduous to maintain, and infuriating to use. They violate the architect’s version of the Hippocratic Oath: First, make it work.

The exuberance of Gehry’s style has made it difficult for people to see his canny, spectacular deployment of interior space. In Disney Hall, even milling around at intermission becomes an exploratory experience. Wood-encased concrete pillars sprout massive branches, like geometric trees leading the eye to lower levels, up through skylights, and out the windows to the building’s alluring skin. In the auditorium, great sails of Douglas fir swoop down from the ceiling, and the organ’s wood-clad pipes glow above the stage. The audience wraps around the stage, virtually eliminating the distinction between good seats and bad.

Disney Hall boasts a form so unmistakable and alluring that photographs invariably present it as a freestanding sculpture against a neutral background. But Gehry has registered everything the setting has to offer—the trove of important buildings in the surrounding blocks, the ravishing but dilapidated Art Deco downtown at the foot of Bunker Hill, the mountains levitating above the distant haze. Disney Hall is not an orchid in the desert but the most beautiful piece in an urban puzzle. The hall spills its glamour into the street, at once sublime and unpretentious.

If I dwell on the glories of Disney Hall, it’s because they dramatize what Gehry might have bestowed on New York, too: a big, ambitious work, powerful and generous enough to act as a focus of civic life. Instead, his best building here is the IAC headquarters, which echoes Manhattan’s twisting shoreline with a series of upended waves. It’s an elegant mixture of stardust and rigor, but you need an ID card to see the inside. At least it’s more than a façade. With the 76-story Beekman Tower, another Forest City Ratner project and Gehry’s first residential high-rise, he has done what New York forces so many architectural auteurs to do: slap a mannerist veneer onto a standard form.

“I started by doing a schlocky New York–style building. Then we analyzed the premium for adding some extra height. We modeled a twisting tower, but that doesn’t work in an apartment building because the plumbing doesn’t line up. At meetings, the layout lady kept saying There’s no Frank Gehry here, I can’t sell it! So I came up with the idea of bay windows.”

Gehry realized that he could preserve an economical structure but shift the windows so that they protruded from a different point in each apartment. Then he could costume those staggered bays in flowing steel. He wanted the dramatic drapery of Baroque sculpture. “I came in and said to a young designer, Do you know the difference between Michelangelo folds and Bernini folds? She said yes. I said, Fine, do Bernini folds.”

For a while, it seemed as though this project, too, would add to the architect’s miseries. Ratner halted construction halfway up and toyed with the idea of saving money by leaving it stunted. Eventually, he extracted concessions from the construction unions, and the tower resumed its upward march. The result will be an ordinary structure in a shiny dress.

The completion of Beekman Tower keeps Gehry yoked to Ratner for now, and the normally unguarded architect has retreated into silence, broken only by a single boilerplate press release. (“We remain extremely proud of our work … ” etc.) Even if he were never to work again, he has transformed enough pockets of the world to make him a Paul Bunyan among architects. He just hasn’t had a chance to change New York, which loved him too timidly and too late.

View the Slideshow