If there’s one patch of New York that deserves a dose of weirdness, it’s the messy, odd-angled intersection where Astor Place swerves into East 8th Street to form the tattoo-parlor boulevard of St. Marks Place, and where Fourth Avenue sprouts an offshoot in Lafayette Street. The snarl creates a plaza of sorts, and several shard-shaped blocks. On one of these sits the bulky brown Foundation Building of Cooper Union, a distinguished incubator of unconventional thought in architecture, art, and engineering. The area is a jangle of architectural styles: cast-iron façades garlanded with putti and cockle shells, an aspiring Parisian hôtel particulier with a Gallic mansard roof, and the copper-domed Ukrainian church built in 1976, when the area reached its deepest grunginess. As Starbucks proliferated and derelicts shuffled off, what the neighborhood needed most was a new wave of inspired idiosyncrasy.

A few years ago, the prospects looked good. Cooper Union leased its parking lot to Ian Schrager, who planned to put up a hotel bursting with flamboyance. Rem Koolhaas and Herzog & de Meuron designed a flared-leg tower riddled with windows that looked like comic-book explosions: Ka-pow! Cooper Union’s dreary engineering center was to be replaced by an office building that would produce more design excitement (and more money for the school). And then there was the site that the school had reserved for its own facility, one that could be as crazy as neighborhood politics would allow.

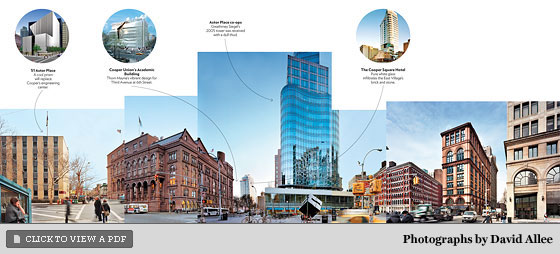

The dénouement has been mixed: an invigorating splash of visionary architecture on the school’s own site, disappointing respectability everywhere else, and a scattershot approach to urban planning that has left what could be one of Manhattan’s most festive plazas wastefully disjointed and bleak. The most hopeful spot sits on the east side of Third Avenue, between 6th and 7th Streets, where Cooper’s cleverly crazy new academic center is going up. Clad in glass, then wrapped again in sheer, lustrous panels that are half steel, half air, the building will positively sashay. Who says engineering can’t be erotic?

This is a relatively staid project for the architect Thom Mayne, the head of the firm Morphosis, a virtuoso of listing walls, jutting canopies, and swooping sculptural gestures. In New York, outlandishness has to be chiseled out of rigid givens, and in this case the external shape—a rectangular box with a eighth-floor setback—was decreed practically before design began.

But an architect of Mayne’s caliber finds resources in restriction. He reached inside the preordained box and scooped out a wildly twisting stairway, so that students could move through their days in spectacle and grandeur. He draped the outer form in a metal skin that folds and, thanks to computerized louvers, moves with the time of day. He tore a patch away to reveal an atrium soaked in daylight. He jacked the whole thing up on thick concrete Vs to keep the ground level open and column-free. It’s sexy, yes, but also strange: With its perforated steel carapace, its mawlike void, and its air of overweening intelligence, the whole thing will look stately and vaguely animate, a cross between a palazzo and a robotic bug. The construction is barely halfway to its full height and won’t be finished until next year, but it’s not too early to predict that the finished product will bring a startled smile to Cooper Square.

On the leasable lots, the story has been less thrilling. Schrager’s financing dried up, and the Related Companies rushed in to erect Charles Gwathmey’s dispiriting condo, a tubular amoeba with a membrane of blue-green reflective glass. The other lot went to the developer Edward Minskoff, who commissioned from the Japanese modernist Fumihiko Maki a stark, sleek thirteen-story office building of black glass, black granite, and white-painted metal. Floating above a glass-wrapped lobby on a traffic island of its own, the collection of cool angular masses looks as if a truncated Trump Tower had been grafted onto an Apple store. At MoMA, this kind of bespoke modernism complements a corporate cultural entity and midtown’s pin-striped aesthetic, but Maki’s refinement will just leach a little more funkiness out of the East Village.

Cooper Union did not commission the Gwathmey condo and it has nothing to do with Maki’s design, but the school has nevertheless helped to corporatize a once raffish and still artistically fertile area by signing away control. With all its land, its reputation, and its roster of talented graduates, it should long ago have managed to surround itself in a ring of daring. It might also have led a concerted effort to unify the rare open spaces, wide sidewalks, and verdant triangles into a landscaped piazza, with cafés, benches, perchance a playground, and maybe even one of those fancy new public toilets or a TKTS booth. (The city does have some improvements in the works.) Instead, Cooper settled for an inhospitable traffic junction, declared its desire for high-quality design, demanded the right to rubber-stamp the choice of architects, and then granted the developers a free hand for the next 99 years. Which is why the Cooper Square Hotel, which has no institutional affiliations at all, will fit so neatly into the area that Cooper Union wrought. It offers the most visible evidence that the area’s core of brick and stone is being replaced by chillier, lighter, more transparent stuff. Carlos Zapata’s white glass tower resembles an upended loaf, bulging slightly westward. The building asserts its brand through curve and height, while its paleness blurs its outlines against the sky and lightens its considerable bulk. It’s hard to look at without thinking about the milky glass of Frank Gehry’s IAC headquarters on West 18th Street, or without noting that the chalky look will shortly date itself.

The design has substantial virtues, especially at street level, where the hotel embraces the block’s long history of low-lying construction. Like a giant flanked by dwarves, the tower looms above a couple of low-rise sidekicks. To the south, an 80-year-old four-story apartment house survives thanks to a couple of immovable residents; the hotel will house its offices in the lower floors, and guests can take their Blackberries or newspapers to a garden out back. To the north, a nifty new yacht-shaped hull will house a multistory bar (which students at Cooper Union will most likely not be able to afford). The handsome complex, which is inching toward final fabulousness, would ornament almost any other part of town. Here, it cements the neighborhood’s transformation from a seedy enclave of oddballs into a strip of more humdrum glamour.