When I came to New York from Virginia, in the fall of 1993, to take an internship at Spy, I was far less interested in the jokey journalists I met—many of whom now work on TV—than in the office manager and the receptionist. They were impeccably thrifted and retro-coiffed college roommates who seemed to hold the keys to a mythic and fully realized downtown bohemia right next to the packs of unfiltered Luckys in their vintage Bakelite purses. Compared with the careerist dorks, their world was super beguiling.

Among their friends was a good-looking guy named Craig Wadlin, who’d gone to art school at Cooper Union and, along with six of his classmates, formed a facetiously named collective called Art Club 2000, which sought to send up consumerism and identity politics by, among other things, taking group self-portraits of its members dressed in identical outfits from the Gap. They exhibited these along with a selection of supposedly meaningful detritus from the stores’ Dumpsters—a loss-prevention handbook, two unopened letters from Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and a dirty diaper—and got flown to Europe and elsewhere as avatars of their generation, which was my generation. It was the first time (but certainly not the last) I had that New York experience: Someone I knew had achieved notoriety for something that seemed clever but maybe a little half-baked. They had become art-world famous, and while I didn’t entirely get it as conceptual art, I knew Art Club was cool.

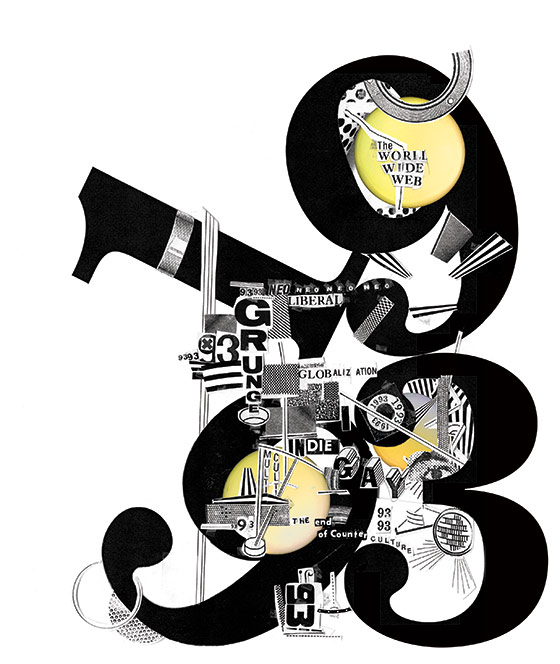

I hadn’t thought about Craig in years when I saw the invitation to an exhibition at the New Museum, “NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star,” which opens this month and is named after an album recorded that year by Sonic Youth, the postpunk Brahmins of that era. It proposes to show, through a selection of supposedly meaningful detritus from the Dumpster of 1993, that that hazily innocuous-seeming year actually changed the world.

As it turns out, twenty years on, Art Club 2000 is still cool: The New Museum invite opens to a photograph of its members, pale and thin and then young, lounging with Gap shopping bags at a Conran’s home-furnishing shop, which the museum’s head curator, Massimiliano Gioni, tells me is a parody of fashion and identity politics that also partakes of fashion and identity politics—for him a paradigmatic early-nineties two-step. The invitation also includes a somewhat comically truncated time line of lively events from that year, designed to suggest that somewhere between Bill Clinton’s inauguration and the end of Saved by the Bell, the release of “Whoomp (There It Is!)” and the bombing of the World Trade Center, AOL 2.0 and the siege at Waco—that somewhere in there a new moment began. And that’s just the beginning of the argument: Throw in Rudy Giuliani’s election, the release of Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, RuPaul’s “Supermodel,” Philadelphia, and Dazed and Confused—and, let’s not forget, River Phoenix’s death—and it all adds up to an era of casual and commercial identity politics and the relentless marketing of self actually does comes into focus. That is, the era in which we’re still living today.

Nostalgia has a life cycle, and usually it runs about twenty years: If you look back at press accounts from the early nineties, for example, there was a lot of talk about the seventies revival, and today Doc Martens are back on-trend and this April’s Coachella is being headlined by Blur, Wu-Tang Clan, Dinosaur Jr, and Moby. Besides, the anointing of particular transformational years is always somewhat arbitrary, probably even more dubious when it’s a 38-year-old curator (who once did a show called “Younger Than Jesus,” with an age cutoff for artists at 33) celebrating a year he spent at university. Since I was in school that year too, maybe my memories are muddled by self-mythology, too.

But flipping through the exhibition catalogue, I see their point—and it’s hard to argue with. In many ways, 1993 did give us our world: globalized and multicultural, libertarian and technocratic at once, target-marketed, relentlessly digital and relentlessly individual, without distinctions between the pursuit of culture and the pursuit of wealth. To put it another way, 1993 might have been the last year of the sellout, when the principle of resistance to the smooth and efficient running of the market began to collapse into our culture of collaboration. It was the year of the first web browser and the forging of both the European Union and NAFTA. Bill Kristol was writing, in Commentary, of how to rebrand conservatism as rebellion in the face of Clinton’s win. MTV’s cultural metabolism was probably at its most rapacious, Tony Kushner brought Angels in America to Broadway, and Toni Morrison won her Nobel. Atlantic Records invested in indie label Matador and Walt Disney bought Miramax. Pulp Fiction, Clerks, and Reality Bites were all in production. Marc Jacobs’s grunge collection was for spring ’93. Harmony Korine was writing Kids, and the former insult-comic editor of Spy had taken over Vanity Fair. In other words, niche markets were becoming mainstream propositions—and soon gave us the entire gloriously fractured culture we’re unavoidably (and more often than not wirelessly) connected to today.

Okay, breathe. First, the web. Nineteen ninety-three was the year that gave us Internet inevitability and triumphalism—not just the first web browser, Mosaic, but the magazine that would make sense of it by celebrating it and codifying an overarching (and at the time what seemed like overreaching) ideology around it, Wired. One of the magazine’s founders, Louis Rosetto, called its launch “a revolution without violence that embraces a new, nonpolitical way to improve the future based on economics beyond macro control, consensus beyond the ballot box, civics beyond government and communities beyond the confines of time and geography.’’ Is that jargon impossibly dated or impossibly contemporary? It’s hard to say, but it was the can-do opposite of the cyber-dystopias that William Gibson had been churning out about the same techno future (his book that year: Virtual Light). Within a few years, my scrubby artist friends were making far more money designing websites than I was as a journalist. And for Gioni, the New Museum curator, the infinite present of the web might be its most distinctive feature: 1993 inaugurated our archival era—“the first time from which you can sort of retrieve everything.” For a while, he says, they were thinking of calling the show Total Recall.

Another Wired founder was Kevin Kelly, who came to Silicon Valley utopianism by way of Whole Earth Catalog DIY, and whom I called to ask to look back on what he helped cheerlead into ubiquity. What he said he and his fellow futurists didn’t foresee was how the Internet would be overrun by user-generated content and the principle that everything should be free. And then he added, “My youngest son is 16, and when he was 10 or 11, he asked, ‘How did you get on the Internet without computers?’ He kind of understood how computers might not exist—he could picture that—but he couldn’t imagine the Internet not being there. That was impossible to imagine.” It’s not that easy for me, either, and I was there, calling the reference desk at the library.

Second, 1993 marked the inauguration of Bill Clinton and the arrival of neoliberalism and globalization—and the subjugation of every single political principle, liberal and otherwise, to the growth imperative. Clinton signed NAFTA, helping shepherd in globalization and hurry along America’s deindustrialization, and began the bubblelicious process of deregulating Wall Street. There were a few rumbles on the left, but they were the rumbles of a dying rearguard, afraid of what became known as the ownership economy. But neoliberalism was the agreed-upon consensus—and not all that far from the one that elected Rudy Giuliani mayor of New York. (The New Museum now sits on the Bowery, of course, which in 1993 was still Skid Row.) Clinton promised a Cabinet that “looked like America,” but as Thomas Frank, then the editor of the disgusted leftist DIY journal The Baffler and not yet the sage of What’s the Matter With Kansas?, put it to me when I called him to talk about 1993, “They looked on the surface like America, but they didn’t express America. They acted like Wall Street.”

Which brings up the third thing the New Museum plausibly argues really exploded that year—multiculturalism and identity politics. This Gioni & Co. do mostly by showcasing actual art—especially from the 1993 Whitney Biennial, a hugely controversial show devoted to work by mostly unknown artists and largely on the subjects of gender politics, sex, race, and AIDS. The clothing company Benetton, which had so masterfully made multiculturalism a “progressive” marketing strategy (“The United Colors of Benetton”), had produced, the year before, a billboard advertisement around a photograph of a man dying of AIDS. Something had surely changed in the years since President Reagan wouldn’t acknowledge the disease and Mayor Koch wouldn’t adequately address it if you could sell some T-shirts by selling AIDS awareness. Or combine, as we all do today, our self-defining higher consciousness with our conscientious consumption choices.

That anxiety, as I remember it, was the concern of the day. Much of The Baffler’s disgust was fueled by the disappearance of the distinctions between the subcultural and the mainstream, the looming co-optation of everything. A new magazine that year was Might, Dave Eggers’s so-earnest-it-was-insolent predecessor to McSweeney’s and The Believer. At the time, I was, like most of my friends, convinced that the great promise of our generation lay in refusal. Itchy, amniotic heroin was the drug of choice at that time, and one of my closest friends in college even had the word LOSER tattooed across his chest: The “o” was his nipple. All that seems to me now, living in a world that has come to so uncomplicatedly venerate the entrepreneurial spirit—winners and disrupters and ted talkers who worry about “scaleability” and who want to make the maximum possible impact on the world—impossibly archaic. But back then everyone was so anxious about “selling out” and preserving the purity of whatever it is that we were or had or didn’t want to be that we couldn’t even see what we actually were trying to do was be successful while still holding on to contempt for the idea of success.

And even then, the word sellout was already losing its meaning: Countercultural gestures had already become things people were willing to pay for. Kurt Cobain agonized so catchily about co-optation that, in 1992, Nirvana bumped Michael Jackson off the top of the charts. When the band appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, its singer wore a T-shirt that read CORPORATE MAGAZINES STILL SUCK. But if that was a heartfelt complaint—and it’s hard to tell how much it was irony and how much self-inoculation—it was a complaint giving its last gasp. In 1993, Jane Pratt, then 30, the founding editor of the “alternative” teen magazine Sassy, was quoted wondering if the fashion-world baby-boomers she saw at Pearl Jam concerts “were there to get ideas, rip them off, and sell them back.” But she had already signed on as host of a Fox daytime talk show; and her competitors were pumping ratings by hosting a rotating cast of New York’s Club Kids.

Suddenly, success had stopped being something to be angsty about: Multiculturalism and identity politics insisted that everyone’s voice was worth hearing, and why would anyone on the margins complain when invited to partake of the piping-hot center of the culture? To complain made you seem like a member of the pathetically bland, imperiled mainstream. And, by 1993, anyone with any intuition could see that put you on the wrong side of history.