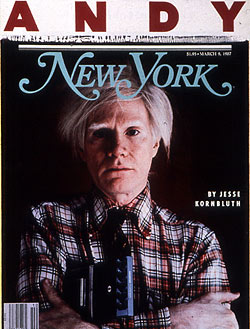

From the March 9, 1987 issue of New York Magazine.

The first sign that there was something wrong with Andy Warhol, that he might be a mortal being after all, came three weeks ago. It was a Friday night, and after dinner with friends at Nippon, he was planning to see Outrageous Fortune, eat exactly three bites of a hot-fudge sundae at Serendipity, buy the newspapers, and go to bed. At dinner, though, he felt a pain. It was a sharp, bad pain, and rather than let anyone see him suffer, he excused himself. And as soon as he got home, the pain went away.

“I’m sorry I said I had to go home,” Warhol told Pat Hackett a few days later as he narrated his daily diary entry to her over the phone. “I should have gone to the movie, and no one would ever have known.”

In fact, no one remembered. And if anyone suspected trouble, it was dispelled the next week by Warhol’s ebullient spirits at the Valentine’s dinner for 30 friends that he held at Texarkana with Paige Powell, the young woman who was advertising director of Interview magazine by day and Warhol’s favorite date by night. Calvin Klein had sent him a dozen or so bottles of Obsession, and before Warhol set them out as party favors for the women, he drew hearts on them and signed his name. On one—for ballerina Heather Watts—he went further, inscribing the word the public never associates with Andy Warhol: “Love.”

The following afternoon, the pain returned. Brigid Berlin, his friend of 24 years, was with Warhol at his studio at 22 East 33rd Street. She was on her way to a London spa to lose weight, but she felt like one last chocolate binge. Warhol had a big box, so they went upstairs for one of the most familiar rituals of his life—someone acting out while he watched. “I’m dying for one,” he confessed. “But I can’t. I have a pain.”

Warhol spent most of that weekend in bed. On Monday, for the first time in six years, he didn’t go to work. That morning, he canceled his appointments with his exercise trainer for the entire week. On Tuesday, he still wasn’t well, so Paige Powell canceled a lunch for potential advertisers. That night, however, Warhol and Miles Davis were scheduled to model Koshin Satoh’s clothes at the Tunnel. And there was no way Andy Warhol could have tolerated an announcement that he was indisposed.

“Andy stood in a cold dressing room for hours, waiting to model,” says Stuart Pivar, a trustee of the New York Academy of Art and, for the past five years, Warhol’s best friend. “He was in terrible pain. You could see it in his face.” Still, Warhol went out and clowned his way through the show. Then he rushed backstage.

“Stuart, help. Get me out of here,” he gasped. “I feel like I’m gonna die.”

Warhol knew that the problem was his gallbladder, and that surgery was long overdue. But he had an even bigger problem with traditional medicine. In 1968, as he lay in the emergency room of a downtown hospital after Valerie Solanas had shot him, he heard doctors tell his friends there was no chance of his survival—an opinion they changed, he said, only when one friend announced that the patient was famous and had money. Ever since then, he feared doctors so much that when he went to auctions at Sotheby’s, he turned away to avoid even a look at New York Hospital. “If I go into a hospital again,” he confided to Beauregard Houston-Montgomery, “I won’t come out. I won’t survive another operation.”

But Warhol didn’t ignore his health—he just redirected his concern about it. He consulted nutritionists, popped vitamins at every meal, was treated with tinctures, and carried a crystal in his pocket. Two weeks ago, when the pain kept coming back, he visited one of these practitioners. “She manipulated the gallstones,” Warhol told a friend, “and they went into the wrong pipe.”

The pain didn’t go away, and Warhol finally agreed to surgery. Powell called him at home that Friday and asked him to come in and sign a copy of the new issue of Interview for Dionne Warwick. “I can’t right now,” he said. How about the ballet on Sunday? “Don’t cancel.”

That Saturday, surgeons at New York Hospital removed Warhol’s gallbladder. That night, he was awake and stable. At 5:30 on Sunday morning, however, he suffered a heart attack. Doctors worked for an hour, but Andy Warhol was right for the last time. He died, at 58, without regaining consciousness.

The news of Warhol’s death moved quickly through the city, and clusters of friends gathered to mourn. Many cried as if they’d lost a father. But as the eulogies came out, a more Warholian feeling began to overshadow this grief. It was unavoidable, really, and as the days passed, some of the people who knew him best began to say it: Andy would really have enjoyed this.

’He sure was famous,” Paul Morrissey remarked the day after Warhol’s death. In the late sixties, Paul Morrissey directed Warhol’s films—and managed his business. And yet, as the articulate director talked, it was almost as if he were realizing, for the first time, that Andy Warhol was even more famous than he had always wanted to be.

Paul Morrissey wasn’t the only close friend to be surprised by the torrent of good feeling that suddenly surrounds the name of the man who, for the last decade, was widely regarded as nothing more than New York’s most ubiquitous partygoer. Paradoxically, it took death—for Warhol, the ultimate act of conceptual art—to focus, frame, and fix his ever-changing image.

That paradox is only the first of many surrounding Warhol. He is probably best known for his epigram “In the future, everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes,” yet he managed to extend his own fame by almost a quarter of a century. His name is associated with the drug taking and sexual promiscuity of the sixties—but for the last five years of his life, he worked out at least three times each week and was home most nights by eleven. He created a life for himself that was more regular than a railroad conductor’s—and complained to friends that things were not fun. He was, for the last decade, the CEO of a multi-million-dollar enterprise—and he both loved that business for providing him with a family and hated the burden that it represented. And, most of all, he was a painter in the great romantic tradition who hid his real seriousness under a wig that he dyed platinum.

“If I go into a hospital,” he told friends, “I won’t come out. I won’t survive another operation.”

The creation of the persona that we know as “Andy Warhol” may not be, as some are saying, his greatest artistic achievement, but it was certainly his first priority. “If you wear a wig, everybody notices,” he explained to a friend. “But if you then dye the wig, people notice the dye.” That was basic Warhol—work with the surface, go for the joke, deflect attention from whatever there is about you that’s unattractive.

As a result, when we think of Warhol’s art, we think first of the silk-screened Campbell’s soup cans; Brillo boxes; multiple images of Marilyn Monroe. The creator of that art always made his work seem easy—something that could be run off by assistants while the most widely known artist since Picasso was out becoming more famous. But Warhol was more than a prankster who, perversely, exalted the most banal images of American commerce. With Lichtenstein and Rauschenberg, Warhol created art that defines the glossy superficiality, manic denial of feelings and process, and underlying violence of the sixties. In the seventies, Warhol almost single-handedly revived portrait painting. And in this decade, he took his ubiquitous camera—which many clubgoers regarded as nothing more than a social prop—and made a triumphant debut as a photographer.

One of his achievements has seeped so deeply into American culture that it’s hard to remember a time when it wasn’t here: Andy Warhol connected art to fashion and to business. In the media, he simply saw no distinction between advertising art and editorial art—except to note how much better advertisements and commercials usually looked than the articles and television shows that surrounded them. At Interview, and in his own work, Warhol blurred the traditional distinctions and encouraged the young photographers and artists he hired to break boundaries, too. The result was a graphics explosion that helped revive New York as the world capital of hard-edged style.

Warhol’s love of change, his willingness to experiment, and his remarkable productivity created yet another paradox—he was as influential in other fields as he was as a painter. The films he made in the sixties are, deliberately, remarkably boring. They have no story, no camera movement, and no apparent direction. They’re rarely seen now, and yet they’re clearly an influence on such promising new directors as Jim Jarmusch. In that same period, Warhol was the godfather of a music scene that produced the Dom, a multimedia dance club that was the model for all others. Warhol’s silver-foiled “Factory,” with its hangers-on, poseurs, and amphetamine addicts, also produced the Velvet Underground, the group that invented punk rock twenty years too early; when they performed in Los Angeles, with Gerard Malanga doing his whip dance in tight leather pants, a young Jim Morrison was there to watch and learn. A decade later, David Byrne went to school on Warhol’s deliberately opaque image and, for both the Talking Heads and his films, devised the postmodern equivalent of Warhol’s blank, flat-affect persona.

Not many artists would welcome such appropriation or applaud the fortunes that the second generation made. But Warhol was delighted to see any new talent succeed. Whenever Interview’s editor, Gael Love, had trouble deciding on someone for the cover, Warhol would say, “Oh, just use any young person.” Without doubt, he loved youth because the young weren’t concerned with the three subjects he dreaded most: age, illness, and death. But he also loved the ideas and styles that they were creating—and that he could use.

So when Warhol appeared in rock videos, when he painted with Jean-Michel Basquiat and starred in his own show on MTV, he was doing more than refreshing his image—he was doing research and development for his art. This strategy worked. “When people ask me what young artists I’m interested in,” Julian Schnabel remarked last week, “I say,’ Andy Warhol.’ “

That Warhol embraced change is hardly surprising, considering his background and his childhood. His parents were Czech immigrants; his father worked in the coal-fields of western Pennsylvania. Warhol was a hypersensitive child who lost his pigment at eight and was henceforth known around the neighborhood as Spot. Later, he would claim that by ten, he had suffered three nervous breakdowns.

At fifteen, a year after his father’s death, the impoverished but precocious Warhol was admitted to the Carnegie Institute. He studied painting and design, graduated, moved to New York in 1949, and set about achieving his twin ambitions—becoming as well known as a movie star and earning enough money to support his mother. That he was pale, balding, and silent was not, in his opinion, a barrier. For a year, he wrote daily letters to Truman Capote, and he even sat in the Palm Court of the Plaza hoping to be mistaken for the writer.

From the beginning, Warhol’s painting blended commercial and fine art. This endeared him to Glamour magazine art director Tina Fredericks, the first to buy a drawing—of an orchestra—from him. “What else do you do?” she asked one day in 1949. “Anything,” he said. So she asked Warhol to draw some women’s shoes for the magazine. “A few days later, he came back with drawings of battered, worn shoes,” Fredericks recalls. “They were terrific, but they wouldn’t sell shoes.” Warhol was eager to please; the next time he showed up, his drawings were of shiny new shoes.

Warhol soon became so sought after as a shoe illustrator that he hired assistants and started—far from the eyes of his employers—what was, in effect, the first of his factories. In 1955, Geraldine Stutz hired him as the exclusive illustrator for I. Miller; two years later, he won the Art Directors’ Club Medal. Now the cold-water flats and roommates were behind him. With his name listed in the “Fashion” section of a book called A Thousand New York Names and Where to Drop Them, he and his mother moved to a four-story town-house on Lexington Avenue at 89th Street. “Andy became rich before he ever sold a painting,” says filmmaker Emile de Antonio.

Though he was always polite in public, he had a childlike ability to read people.

At that time, de Antonio was an artist’s agent who’d found work for Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg doing display windows. When Warhol made some paintings, he showed them first to de Antonio. These paintings were of Coke bottles, and they came in two styles. In one, the bottle had the hatch marks that were the sine qua non of Abstract Expressionism. In the other, it was stark, unadorned, and outlined in black and white.

“One of these is crap,” de Antonio said. “The other is remarkable—it’s our society, it’s who we are, it’s absolutely beautiful and naked, and you ought to destroy the first and show the second.”

Ivan Karp, then working for Leo Castelli, shared de Antonio’s enthusiasm. Karp wasn’t able to place Warhol’s work at the gallery, so Warhol’s New York debut as a painter was in a Bonwit window. Irving Blum gave him a show in Los Angeles in 1962, but his soup cans didn’t sell. “A gallery dealer up the road bought dozens of Campbell’s soup cans at the supermarket, put them in his window, and said, ‘Buy them cheaper here—60 cents for three cans,’ ” Blum recalls. “And so there was a lot of hilarity regarding Andy. And not a great deal of serious interest.”

But with encouragement from Karp and Henry Geldzahler, then a young curatorial assistant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Warhol pressed on. “What should I paint?” he asked them, in his first foray into market research. Self-portraits, Karp said, and cows. Death, said Geldzahler—car crashes, disasters, electric chairs. Warhol followed every suggestion. Then he directed his question to a woman at a dinner party. “Well, what do you love most?” she shot back. And Warhol started painting money.

Warhol’s first studio was a firehouse on 87th Street off Lexington Avenue. It had no heat or running water. The rent was $100 a year. No one was eager to go there, which was fine with Warhol. In 1963, he was very busy making silk-screen paintings with his first assistant, Gerard Malanga.

“I remember when Kennedy was shot,” Malanga says. “We went back to the firehouse and made a silk screen of Dracula biting a girl’s neck.” Warhol, who had been desensitizing himself for years by playing songs over and over at top volume, never missed a stroke. “Everything was just how you decided to think about it,” he said.

That fall, Warhol moved to an abandoned factory on 47th Street off Third Avenue. He allowed Billy Name to live there, a decision with more consequences than anyone could have anticipated. Name not only decorated the crumbling loft in silver foil and dragged in a couch large enough for an orgy, he attracted Rotten Rita, the Duchess, Ondine, and the rest of that crew—freaks who turned the Factory into the city’s ultimate freak hangout. The hustlers, transvestites, and other exhibitionists attracted the obligatory second wave: society kids like Edie Sedgwick and Susan Bottomly.

Warhol, who collected many things but loved most to collect people, soon mastered the trick that became his greatest source of power. “Now and then, someone would accuse me of being evil—of letting people destroy themselves while I watched, just so I could film them and tape-record them,” he said. “But I didn’t think of myself as evil—just realistic. I learned when I was little that whenever I got aggressive and tried to tell someone what to do, nothing happened—I just couldn’t carry it off. I learned that you actually have more power when you shut up.”

So Warhol became a mirror, his conversation limited to “Oh, gee” and “Gosh” and—rarely honestly—”That’s great.” The more passive he became, the more outrageously the crowd at the Factory performed for him.

What was Warhol’s role in this massively decadent scene? It’s doubtful that he was an active participant. From the beginning, he hated drugs, and those who used them on a regular basis took care to do so out of his sight. And as for sex, in that department he claimed to be already committed. In the late fifties, he said, he started an affair with his television set; in 1964, he married his tape recorder. He had no time for others. He lived with his mother, lounged around the house, watching TV in the morning, then worked with his assistants—or just watched them make his art—until eight at night, when it was time to go out.

The more passive Warhol became, the more outrageously the crowd at the Factory performed for him.

That Warhol was a voyeur was first suggested by Ondine, who made him leave an orgy in the early sixties because all he did was watch. But that Warhol had crushes is undeniable. They started with Capote and probably included most major male film stars of the last four decades. (A few crushes were closer to home. In the early eighties, Warhol lived with a handsome and talented young man who chafed at life in the artist’s shadow, left New York, and subsequently died of complications from AIDS—but no one who saw them together believes the relationship was consummated.) Why did Warhol flinch from all human contact? Because, as he once quipped, “sex is nostalgia for sex.” Although one of his longstanding fantasies was to open a house of prostitution, the fantasy role he chose for himself was that of cashier.

Inevitably, Warhol’s harmless early experiments as a filmmaker—such as the one of Robert Indiana eating mushrooms—were followed by more voyeuristic efforts that showed, with clinical detachment, would-be “superstars” having sex and delivering stoned monologues. But the content was all the same to Warhol, who could bring the same appreciation to eight hours of film of the Empire State Building as he could to a 30-minute reel of an actor being sexually serviced. The purpose of filmmaking, for him, was partly social—”a way of getting to meet and know more people,” says Paul Morrissey. And, of course, there was the economic angle. “Andy always thought,” Morrissey says, “that films would be where we’d make money.”

With Chelsea Girls, a 1966 movie about people who hung out in the Chelsea hotel, they made the Variety charts—and, according to Morrissey, a profit of $100,000. They also struck the deepest nerve to date. “It has come time to wag a warning finger at Andy Warhol and his underground friends and tell them, politely but firmly, that they are pushing a reckless thing too far,” Bosley Crowther wrote in the Times. “A silly review,” Warhol said. It turned out to be prophetic.

By 1967, the Factory was becoming, in Jackie Curtis’s phrase, “the desert of destroyed egos.” Warhol moved his enterprises to Union Square West that year, but the ambience didn’t change: In his passive way, Warhol was power-mad. He pretended to be unobservant, but he knew what was going on and spread malicious rumors to exacerbate the tension.

The tension began to flash back at him. An associate who pressed him on some matter became enraged when Warhol responded, as he invariably did when confronted directly, by becoming more evasive. “Look at me when I talk to you!” the man said. And then he did the unthinkable—he touched Warhol’s shoulder.

On June 5, 1968, Warhol found himself face-to-face with a woman who could not be satisfied with so small a breach. He knew Valerie Solanas well. She’d written a script for a movie called Up Your Ass that was so vile that Warhol thought she was a police agent sent to entrap him. Later, she founded SCUM (the Society for Cutting Up Men) and railed about the perfect world that would be created by the elimination of men.

On this day, Solanas didn’t come to rant. She stepped off the elevator, pulled out a .32- caliber revolver, and fired. Two bullets passed through Warhol’s stomach, liver, esophagus, and lungs. “I can’t breathe,” he said as he fell. His business manager, Fred Hughes, tried to give him artificial respiration, but Warhol said it hurt too much. And it went on hurting for half an hour as Warhol lay on the floor, bleeding and moaning and waiting for the ambulance, quite conscious.

The shooting left Warhol at a crossroads. “Obviously, I should avoid unstable types,” he wrote in POPism, his personal history of the sixties. “But choosing between which kids I would see and which ones I wouldn’t went completely against my style. And more than that, what I never came right out and confided to anyone in so many words was this: I was afraid that without the crazy, druggy people around jabbering away and doing their insane things, I would lose my creativity. After all, they’d been my total inspiration since ‘64, and I didn’t know if I could make it without them.”

And then there was the matter of death. “Since I was shot, everything is such a dream to me,” he said. “Like I don’t know whether I’m alive or whether I died. I wasn’t afraid before. And having been dead once, I shouldn’t feel fear. But I am afraid. I don’t understand why.”

He founded Interview after being refused free tickets to the 1969 New YorkFilm Festival.

Very quickly, Warhol made the conservative choice. “Death is like going to Bloomingdale’s,” he’d tell friends. “It’s nothing.” But that was for effect. In reality—where he increasingly resided—it was time for a major housecleaning.

The Factory was closed. Warhol renovated the Union Square West studio and turned it into an extremely businesslike office. There was a door this time, and it was locked and bolted against the freaks. Paul Morrissey took over the film operations, and Fred Hughes the art business. And Andy Warhol, who went out almost every night until the shooting—going anywhere he was asked because he really wanted to go everywhere—never returned to the fabled back room of Max’s Kansas City.

With more clean-cut people representing him, Warhol was free to explore another medium. Typically, he found one that allowed him to turn his pleasure into work. And, typically, the choice was made by others, not by him.

The catalyst was the New York Film Festival, which, in 1969, inexplicably refused Warhol’s request for free tickets. “Andy was really upset,” Malanga recalls. “He said, ‘If we start a film magazine, they’ll have to let us in.’ ” Interview was duly founded. In the beginning, it was a mildly raunchy tabloid that featured tape-recorded interviews with dubious celebrities and a few movie reviews. Warhol didn’t read it until he began to hear about the magazine’s negative film reviews. Suddenly, he was very interested—and uncharacteristically directive. “I can’t have this,” he announced. “I’m losing all my friends.” From that day on, there has never been a film review—or a critical piece—in Interview.

The seventies are seen as the nadir of Warhol’s career, a decade in which his influence didn’t extend beyond the walls of Studio 54. All he seemed to do was go out and stand around with Bianca, Brooke, Halston, and others of uncertain intellectual inclination. A lively night meant a photo opportunity with Debbie Harry or a sassy look from Jerry Hall. Small wonder that he retreated to the townhouse he’d bought on East 66th Street, where he lived with two housekeepers and two dachshunds.

If Warhol looks bored in photographs taken with celebrities, he usually was. On the shallow level he adored, these people were his friends. And yet he would have gladly forsaken them for people whose names were not known but who had great stories. As much as he valued fame, he preferred what he called the bottom line—the inside scoop, the gossipy, telling fact. He liked hearing it, with all the weird twists and trimmings he believed it carried, and he liked sharing it with close friends. “You’d go somewhere with Andy,” a friend recalls, “and when you left, he’d tell you what really happened.”

Those occasions were infrequent in the seventies. And his art seemed to give him no pleasure. “I just came back from Germany,” he told de Antonio in 1979. “It was so boring. I had to paint industrialists.” De Antonio asked him how much he charged for these portraits. Warhol brightened. “Fifty thousand dollars, unless they have wives and children,” he said. “Then it’s $75,000.”

In retrospect, his portraits—particularly the one of his late mother—are worth looking at, for they testify to a slowly mellowing Warhol. Always a practicing Roman Catholic, he found his own form of confession: Around 1972, he began a diary. Again, the impetus was not to have a daily catharsis, but to turn a bit of pleasure—in this case, a daily phone call to writer Pat Hackett—into work.

“As we were talking every morning anyway,” Hackett says, “Andy decided I should write things down as a way of keeping track of his expenses.”

Five mornings a week, Hackett and Warhol began their days with a phone call that lasted at least an hour. Warhol talked about all the subjects that second-tier friends believed he always avoided. And Warhol, who was invariably polite in public, said what he really thought about people—such as Truman Capote. “Truman was condescending to Andy and called him ‘a Sphinx with no secret,’ ” Hackett says. “But when Andy came back from afternoons with Truman, he was hilarious.”

That Warhol was a brilliant and witty conversationalist with a childlike ability to read people was a secret only his closest friends knew. Right up to his death, he encouraged the public to believe that he was as mute as Harpo Marx. It was easier that way. All you had to do was listen. And if someone went on too long, you just tuned out. Bores found this terrifying—and fled.

One secret that Warhol couldn’t keep was his continuing obsession with money. On this topic, above all others, he was completely focused, a total businessman. “Sometimes he wouldn’t ask me about the magazine for days,” recalls Bob Colacello, Interview’s onetime editor, “and then he would say, ‘How many subscribers do we have in Ohio, and how much do we make on each one?’ ” The realtor who sold Warhol a house in Montauk—mostly an investment, as Warhol couldn’t take much sun—remembers getting calls every few years at the start of the summer rental season. “Warhol’s staff handled the rental themselves,” she says. “They just wanted to know if they were charging enough.”

His friends were shocked by his death, but Warhol had a perfect sense of timing. He hadjust finished his version of the Last Supper.

For all his obsession with finances, this was not the calculating, cynical Warhol of old. Just the reverse: Andy Warhol spent the eighties making sure he gave as good as he got. He didn’t shower people with praise, but as he passed the half-century mark, there was a sweetening in the private Warhol that the public Warhol never bothered to acknowledge.

Paige Powell was the agent of this change. Knowing that Warhol hated holidays, she took him to serve the needy at the Church of the Heavenly Rest on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter. “Andy dragged around garbage cans and poured coffee,” she says. “And he did something that wasn’t on the program—he found Saran Wrap so people could take food home.”

Warhol stayed in touch with the new generation of Factory and Interview staffers, most of them bright, clean-cut, and not interested in exploiting him. He called them “the kids” and worried about them. “How’s your love life?” he’d ask, but not so he could get the information that would give him power. At night, he’d call the magazine. “Are the kids working late?” he’d ask. “If they are, don’t let them go home alone.”

As the inner circle expanded, Warhol became more uninhibited. He collaborated with Basquiat to encourage the troubled young painter to work every day. He consoled Stephen Sprouse when Sprouse’s business failed. He hectored Tama Janowitz into writing the screenplay of Slaves of New York. Through Powell, he met Heather Watts and Peter Martins, got excited about designing a curtain for the ballet, and—after some performances—sent flowers from “Backstage Johnny.”

The cumulative effect of all this friendship—friendship that Warhol was able to acknowledge and return for the first time in his life—was a renewed exuberance for work. Buoyed by the success of his photography show, which featured the usual pictures of banal subjects but showed them cunningly stitched together, he was looking forward to another. He was buying classical sculpture and looking at equipment that would have allowed him to make sculpture with lasers. And, because he was spending so much time with Paige Powell, he was full of schemes for Interview.

Warhol planned to undertake a newsstand blitz—a mad dash across Manhattan, stopping to promote Interview at every newsstand. He would have gone to more trade shows and, on the weekends, passed out more free copies on Madison Avenue. As it was, he was bubbling over with happiness about the magazine’s first condom ad. “A new category!” he chortled.

One thing never changed: At 58, Warhol was the same star-struck kid he was at 19. “You called him, and he answered?” he’d say to Gael Love when she told him of her calls to movie stars. A few weeks ago, he and Powell were sitting at Nell’s with Bob Dylan, Sting, and Ian McKellen. Quietly, he turned to Powell. “Do you believe who we’re sitting with?” he whispered.

When it came to making out a will, however, Warhol was definitely not star-struck; the document includes not a single surprising beneficiary. Instead, the will neatly turns over virtually everything to the newly created Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. This includes $11 million in personal property, film archives, art reserves, and the recently profitable Interview. Another $4 million is in real estate—although this seems like a low estimate, considering that Warhol owned 20 acres in Montauk, 40 acres near Aspen, his town-house, the former Con Ed station on East 32nd Street that houses Interview, and the SoHo building rented by Jean-Michel Basquiat.

The directors of the foundation will be Warhol’s business manager and executor, Fred Hughes; Hughes’s second-in-command, Vincent Fremont; and one of the artist’s brothers, John Warhola. To the extent possible, the directors say, the foundation will continue Warhol’s enterprises.

There are also no surprises expected in the value of Warhol’s art. A catalogue raisonné that was being produced in Germany at the time of his death should be available in a month or two.

“It should give us a good idea of what’s real and what may have been run off without Warhol’s consent,” says an art dealer who’s followed Warhol’s career for 30 years. “And there are Warhol shows in Germany and Austria in the next two months that should give us a better idea of the appreciation in Warhol prices. But already [since his death], we’ve seen the prices of his prime prints—the Monroes, the flowers, the Mick Jaggers—go up an immediate 50 percent.”

That Warhol is a hot property again could be seen in other places last week. In literary hangouts, the talk was of Bob Colacello’s biography of Warhol. Proposed last October, it was commissioned for $400,000 by G. P. Putnam’s Sons a few days before Warhol’s death. At Interview, burly security guards manned the door. Behind them, the walls were dotted with Warhols and the floor was littered with crates filled with Warhol’s most recent art purchases. The effect was eerie—rather like the scene in Citizen Kane in which workers bundle up art treasures in the castle of a man who could buy everything but immortality.

A few weeks ago, Pat Hackett and Andy Warhol had a conversation about John Ford movies. Hackett had just been to see one, and Warhol had a fondness for them, too. “But Andy, they have everything the sixties movies were trying to get away from—scripts, plots, endings,” Hackett said. “Well, maybe that’s the way it really works,” Warhol replied.

Certainly, that was true for Andy Warhol’s life and career. His friends are shocked by his death, but Warhol, who had a perfect sense of timing, had recently completed his version of the Last Supper. It had taken him more than a year, and it is now displayed in a Milan gallery, directly across the street from Leonardo’s masterpiece.

The largest of the silk screens includes two images of Christ, one upside down. In his last interview, with art critic Paul Taylor for Flash Art magazine, Warhol explained that doubled image. “They’re like the two popes,” he said. “The European pope and the American pope.” Taylor asked Warhol who the American pope was. “The American pope is the pope of Pop,” Warhol said, with a self-referring smile.

If “Andy Warhol”—the Warhol of soup cans and the Factory—had said that, it would have been posturing and self-promotion. Twenty years later, with Warhol a changed person, the remark was neither of those things. In 1987, the year that Warhol could not wish death away, it was the bottom line.

Lucy Schulte helped report this article.