I remember the first time the earth moved for me at a museum. My culture-deprived, aspirational mother dragged me once a month from our northern suburb—where the word art never came up—to the Art Institute of Chicago. I hated it. Art seemed so old and boring and not baseball. Then one day, when I was about 9, we stumbled on a couple of small paintings. In the canvas on the left, a man’s head was stuck between the bars of a jail cell; a soldier outside the cell was raising an ax in the air. In the painting on the right, blood was spurting from the same man’s neck, and the soldier’s ax was at his side. Of course the blood and guts were cool. But something else happened. It suddenly dawned on me that these paintings were telling a story. To this day, the work that moves me most—that sweeps me up, even to the point of rapture—vibrates with that sense of storytelling. (The artist, I later learned, was fifteenth-century Italian master Giovanni di Paulo. You can find his sublime The Creation of the World and the Expulsion From Paradise at the Met.)

Summer is a great time to visit art museums, which offer the refreshing rinse of swimming pools—only instead of cool water, you immerse yourself in art. To remind myself of my favorite Western paintings in New York (my criterion for this list), I spent a month dipping in and out of our city’s museums, like the character in John Cheever’s classic short story “The Swimmer,” who swam across the pools of Westchester County one hot summer day. Think of me as your Sister Wendy in swimming trunks.

Not pictured:

• Henri Matisse

Goldfish and Palette (1914)

MoMA

In this staggering aesthetic shot over Cubism’s bow, Matisse turns his guns on Picasso and Paris, a city then enamored with the brilliant, quixotic Spaniard. Complicating the faceted flat space of Cubism, transforming black into light, conjuring blues that hadn’t been harnessed since Giotto, Matisse returns fire—and for me wins the war.

• Joan Miró

The Birth of the World (1925)

MoMA

The first time I saw this smudged abstraction, I wasn’t sure if it was art. I eventually gleaned that Miró’s rickety lines, quasi-crawling baby trapezoid, blurs, blots, and pools of paint are what they are, but they are also about mark-making, process, chance, and control. Abstraction, as it turns out, is among the greatest tools invented by human beings to envision the chaos of the universe.

• Jackson Pollock

Room of eight paintings

MoMA

Looking at these canvases (including One: Number 31, 1950, at right), installed chronologically, reminds me that few artists were less naturally talented than Pollock. That he virtually willed himself to newness, deploying something that had been there since the caves—the drip—then went in search of something else that killed him, makes this a monument to the bravery of creation.

•Frida Kahlo

Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair (1940)

MoMA

That Kahlo has become kitsch (much like the equally groundbreaking O’Keeffe) is one of the great shames of modern art. Can you argue with the audacity and fervid emotion of this canvas, which shows the artist in drag, her hair shorn, wearing what looks to be the clothing of her philandering painter husband, Diego Rivera? It’s painting as magic talisman, evil eye, and self-flagellation.

E-mail: jerry_saltz@newyorkmag.com.

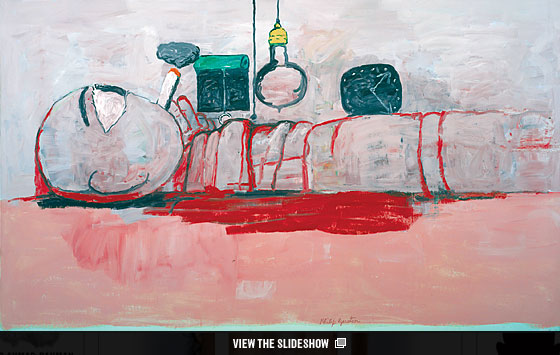

Philip Guston

Stationary Figure (1973)

The Met

In an image reflecting Guston’s egomania, his love of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, his felicitous touch and rosy-fingered color sense, a monstrous, one-eyed figure lies in bed, smoking and staring at a pulsating bare lightbulb. A clock reads 2:25. That’s a.m. In one cartoonish flourish, Guston sums up the dark nights of the soul, when artists wonder if they will ever produce something good.

Photo: ” The Estate of Philip Guston, Courtesy Of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Florine Stettheimer

The Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue (1931)

The Met

Paint as cake frosting; color as shimmering cellophane. This hallucination of a wedding procession on a red carpet spilling out of a department store raises shopping to a batty rite of passage.

Photo:

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Jean-Auguste- Dominique Ingres

The Comtesse d’Haussonville (1845)

The Frick

A showstopper in any context, even at the Frick, which has one of the highest concentrations of masterpieces of any small museum in the world. The girlish 27-year-old countess, already a mother of three and destined to be a historian, scrutinizes us coyly, within a typically sumptuous Ingres setting. The amazing Delft-blue ensemble, her insanely creamy, curving arms”she’s a decadent dessert almost too rich to digest.

Photo: Courtesy of the Frick Collection, New York

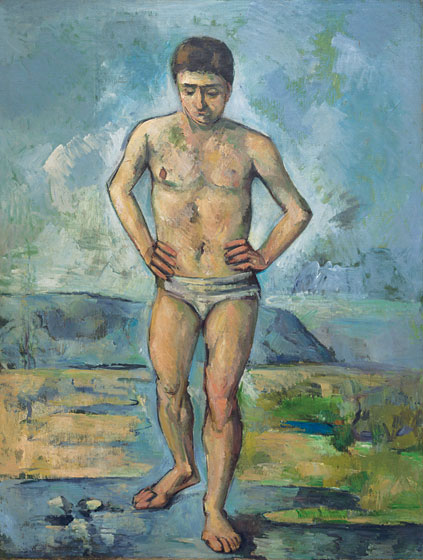

Paul Cézanne

The Bather (1885)

MoMA

Think of this enigmatic boy as stepping into a new optical dimension: He is simultaneously seen from above and below, left and right, surrounded by a subtly destabilized space that will fracture into Cubism. The Bather is the dawn of a new pictorial era. Matisse was right: Cézanne is “a sort of god.” He’s in my top four Western painters along with Velázquez, Goya, and Matisse himself.

Photo: The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, NY

Marsden Hartley

Evening Storm, Schoodic, Maine No. 2 (1942)

The Brooklyn Museum

I am so overwhelmed by the wounded otherness in Hartley’s art that I can’t write about it or him. He defeats me. This is the work that I would most want to live with.

Photo: Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn

Self-Portrait (1658)

The Frick

The artist as monumental Buddha, cloaked foremost in shadow but also in furs and embellished silks worthy of a magus”a poignant counterpoint to his careworn face, staring from beneath the brim of a nearly invisible hat. From that face, Shakespeare could have written King Lear. Rembrandt, Goya, and Velázquez were the painters who opened the door widest to the fullness of human emotion.

Photo: Courtesy of the Frick Collection, New York

Kazimir Malevich

Morning in the Village After Snowstorm (1912)

The Guggenheim

Like an explosion in an airplane factory, the Cubo-Futurist masterpiece depicts gleaming robot peasants in curved metallic shards. The composition of snowdrifts, houses, and people spirals energetically toward a distant sled-puller, and recalls the artist’s childhood”a way of life that predated the Industrial Revolution and outlasted the Russian one.

Photo: Courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, NY

Georgia O’Keeffe

Blue Lines X (1916)

The Met

The visionary painter was one of only about a dozen European and American artists attempting abstract paintings in 1916. The simplicity here is poetic, the blue lines reminding me at once of animal tracks, hieroglyphics, and Barnett Newman’s zips.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Édouard Manet

Young Lady in 1866

The Met

Isolated against a background of unbroken gray (containing Brice Marden’s entire career) is one of the greatest housecoats in the history of painting on one of the period’s greatest models, Victorine Meurent”the nude star of Manet’s once scandalous Olympia. This is what she looked like on her day off.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Thomas Chambers

Staten Island and the Narrows (1835”55)

The Brooklyn Museum

This bewitching picture of white-crested waves, wispy clouds, and gorgeous ships passing between Brooklyn and Staten Island jumps off the wall: How wondrous and magical New York was”and still is. I imagine Walt Whitman on the shore, in his usual state of multitudinous ecstasy.

Photo: Courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum

Vincent Van Gogh

Mountains at Saint- Rémy (1889)

The Guggenheim

A progression of motion and emotion set off by brushwork, color, and Van Gogh’s turbulent sense of surface design. The road, trees, and house in the foreground are reasonably real. But the undulant mountains beyond”under a threatening sky of raw impasto”are haunted with figures, flames, and, in the middle of it all, a blue angel’s wing.

Photo: Courtesy Of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Mortlake Terrace: Early Summer Morning (1826)

The Frick

Although I’m not a Turner fan, this painting speaks to me for its uncharacteristic calm. Instead of the painter’s usual bombast and histrionic portrayals of nature’s violent indifference, or just its special effects, we see the beneficent unity of man and nature. Nothing is forced, there is no drama, and for at least one painting, I love Turner.

Photo:Courtesy of the Frick Collection, New York

Michelangelo Merisi Caravaggio

The Denial of Saint Peter (circa 1610)

The Met

Notice the dramatically gesturing figures, stark lighting, compact cropping, and complex moments of internal and external emotions. That is how Caravaggio essentially foreshadowed modern filmmaking.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Duccio di Buoninsegna

The Temptation of Christ on the Mountain (1308”11)

The Frick

This powerful little canvas once appeared on the back of Duccio’s Maestà in Siena, one of the landmarks of Western painting. But it does quite well on its own. It depicts the moment that Christ rejects Satan’s offer of two marzipan-like cities (Italian hill towns, actually). Note cowering devil slinking off, stage left. (The equally fabulous landmark painting St. Francis in the Desert, by Giovanni Bellini, lives at the Frick as well.)

Photo: Courtesy of the Frick Collection, New York

Sassetta

The Journey of the Magi (1435)

The Met

In a crisscrossing, snow-covered landscape, the three magi follow the star of Bethlehem, fabulous entourage in tow. I am enchanted by the mix of opulence and tranquility and the whimsical pink walls of the city behind them. New York is filled with superb but easily missed sleeper paintings like this.

Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art