On a hot, sticky night in the summer of 1979, Jennifer Rubell, a rising fourth-grader at P.S.6, accompanied her uncle Steve to a small dinner party at his friend Halston’s townhouse. The air-conditioning was cranked to icebox high, and guests—Liza Minnelli, Farrah Fawcett, Ryan O’Neal, and Andy Warhol—were seated in front of a roaring fire. Warhol had a sudden urge to draw Farrah. Halston clapped his hands, and his butler, Mohammad, appeared with folded white napkins and black markers, served on a silver tray. Warhol began, then changed his mind and began sketching the 9-year-old instead. “Your parents are those art collectors, right?” he asked her as he drew. “How do you spell Jennifer?” She spelled it for him several times. “Too confusing,” he said, and wrote, TO J.R. LOVE, ANDY.

“You have to understand that Andy and my uncle were best friends,” says Rubell, 41, laughing as she tells the story. She also recalls being so freaked out by Ryan O’Neal’s lighting up a joint that she begged her uncle to take her home. These are the sorts of formative experiences you have when your uncle was Steve Rubell, the co-owner of Studio 54. He and business partner Ian Schrager eventually lost the nightclub and were imprisoned for tax evasion. When they got out, Rubell channeled his high-gloss sense of where people wanted to socialize into their boutique hotels. Hospitality, along with art collecting, became the family business.

Jennifer’s parents, Don and Mera, a physician and a schoolteacher, had started buying contemporary art in the mid-sixties on a $25-a-month budget. Their discernment and enthusiasm built their collection into something that fills an entire museum in Miami today.

For the Rubells, it wasn’t just about collecting objects: Mera and Don delighted in getting to know the artists and talking the (somewhat academic) art talk, which they slip in and out of like it’s a native tongue (they even kvell over Jennifer in art-speak). This world, with its language and rituals, intrigued Jennifer growing up. “My parents would go to art dinners, and I’d ask them to tell me every single detail, not just what was served but what the table was like, who was there,” she says. “In my mind, it was so much more fantastical than it was.” In the eighties, her parents became renowned for their Whitney Biennial parties at their Upper East Side townhouse, with guest lists that included Keith Haring, Julian Schnabel, Warhol, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. They were friends with Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, and Jeff Koons, for whom Jennifer interned when she was 19.

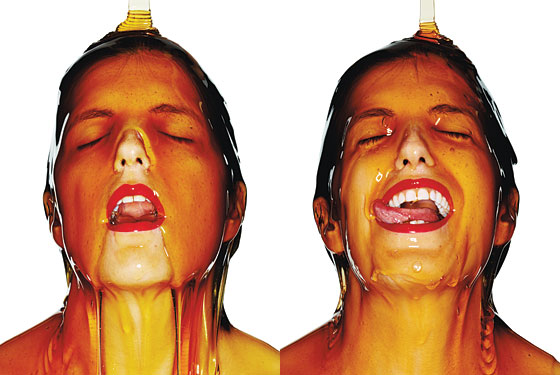

Growing up in that environment was, for Rubell, exciting as well as a bit intimidating, since she was trying to find her way creatively. Her older brother, Jason, 43, who together with their parents runs the family’s two hotels (the Albion in Miami and the Capitol Skyline in D.C.), is also a collector. But Jennifer worked in food, then wrote about food, and then became known as a “food artist.” At the moment, she’s preoccupied by the industriousness of bees and their honey.

Becoming a conceptual artist “was a huge leap of faith on Jennifer’s part,” says her mother. “Just imagine your parents thinking you’re the bad artist in the family.” After all, her parents were far too knowledgeable to be able to be unconditionally supportive. “For years we said, ‘It’s so difficult to be friends with an artist whose work you don’t like,’ ” says her father. It would be hard for Jennifer not to internalize this. Besides, “Look at how many collectors’ children are artists,” she says. “It’s a number approaching zero. And because of my parents, even if I was half-decent, I knew people would think it was handed to me.”

After graduating from Harvard in 1993 with an art-history degree, Rubell focused on food. This wasn’t a surprise: Her mother says she threw her first dinner party when she was 9. “The first course was tomato juice in wine glasses with lemons on the edge,” says Rubell. “Very seventies.” She attended the Culinary Institute of America, interned for Mario Batali at the Food Network, then moved to Miami, where she had plans to open Jennifer’s, a Morris Lapidus–designed restaurant, in the early nineties. The restaurant “didn’t work out, thank God,” she says. For nearly a decade, she worked on the food and entertainment side of the hotels. She also became known in South Beach for her extravagant dinner parties, which led to her becoming a food and home-entertaining columnist for the Miami Herald and Domino and writing Real Life Entertaining: Easy Recipes and Unconventional Wisdom.

Around the time Domino folded in 2009, Rubell was reassessing her career. She’d been living in New York for several years and had become a mother—daughter Stevie, named for Rubell’s uncle, is now 5 1/2;—and “realized that there was no conceptual or intellectual underpinning” to her writing. “It was a totally unsatisfying path.” But she wasn’t about to write off food.

Since 2001, Rubell had been organizing her parents’ annual breakfasts at the Art Basel festival in Miami. Her deconstructive approach to feeding big groups, she realized, resembled the practices of a conceptual-art movement known as “relational aesthetics,” where the artwork creates a social environment in which people participate in a shared activity. At a breakfast in 2007, for example, instead of a traditional buffet, Rubell laid out 2,000 of each of the following: pairs of latex gloves, hard-boiled eggs, croissants, and slices of bacon, for guests to feed themselves. Rikrit Tiravanija, the artist whose work involved cooking for gallery-hoppers, “had already done his performance with food in the nineties,” she says, “but relational aesthetics definitely impacted my belief that what I was doing was art.” Art Basel–goers recognized it, too, asking Rubell’s parents who the artist was behind the breakfasts. “That echo was louder and louder every year,” Mera says.

Jennifer was good at this, and it filled a need: So much of the art world is about providing a context for social interaction—she’d witnessed it firsthand. And interaction fascinates her. She soon began to get commissions to do her brand of provocative catering from friends and arts organizations.

When Performa 09 director RoseLee Goldberg invited her to participate in the performance-art biennial in New York, Rubell crossed the now-blurry line between arty event planning and art installation. Her multiroom Creation, at the former Dia Center for the Arts building in Chelsea, was inspired by the first three chapters of Genesis. Food was spread among three floors and included a ton of ribs progressively drenched by a honey trap mounted on the ceiling, referencing the creation of Eve; three felled apple trees; and seven Jacques Torres–chocolate mini-facsimiles of Jeff Koons’s “Rabbit,” with hammers provided to break them. Times art critic Roberta Smith described the event as having “melded installation art, happenings, and performance art with various Old Testament overtones, while laying waste to the prolonged ordeal that is the benefit-dining experience.”

Rubell was now being called a food artist. Her whimsical, sometimes disturbing, and always spectacular events at museums and art fairs around the country matched perfectly with the lavish, self-reflective hobnobbing spirit of the contemporary-art world. They also commented on the art itself, tweaking and reveling in its consumability. Last year, she produced a dinner for the Brooklyn Museum’s annual benefit. The theme, “Icons,” allowed Rubell to honor her favorite artists: a giant piñata of Andy Warhol’s head decorated the lobby; a table arranged with 150 roasted rabbits evoked Joseph Beuys’s performance piece How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare; “drinking paintings”—blank stretched canvases, each with a tank in back and a spigot in front dispensing dirty martinis, bourbon, gin-and-tonics, white wine, rum-and-Cokes, screwdrivers—were hung on the walls, referencing Jackson Pollock’s “drip” paintings.

The drinking paintings were a personal breakthrough because Rubell was moving away from food and more clearly establishing her artistic objective. Interaction, she explains, is her medium; food had been the means to engage. “I’m interested in making art that people want to see and can use to understand what’s happening inside contemporary art. The minute you give people something they can participate with, it gives them access to it, because they’re a part of it.” The drinking paintings solved another problem: Rubell had found a way to “create durable objects that contained the ongoing possibility of interaction.”

Creating something durable also drew her parents’ attention. “My contemporary-art education comes 100 percent from my family, and their narrative of what’s happening in contemporary art is laid on a matrix of collectibility,” says Rubell. “Because they hadn’t validated ephemeral work, I hadn’t validated it in my mind.” She wanted them to understand her work, which is, in part, a physical manifestation of their ongoing conversation. “Jennifer challenged us to go into something that we understood the least,” says Mera, now owner of several drinking paintings—currently the only art to adorn the walls of the couple’s living room. “But we are under instructions from her to not behave as parents or as our usual enthusiastic collector selves—we can’t stop talking about artists we discover. We feel so lucky to have this creative force inside of our family.”

Rubell is now confident enough to identify as a conceptual artist not only within her family but out in the world, too. Not that her foodie friends fully appreciate the importance of the distinction. Batali deeply admires his old friend and sees her as his “fire iron”—the two cooked up the concept of the “vegetable butcher” for his Eataly over a late-night dinner at Del Posto one night (she even did the job for a while). “She’s always at my restaurants in the inception-and-development phase,” he says. As for her being a conceptual artist, he is supportive, but, he teases, “I just hope she doesn’t become Karen Finley standing in a bucket of shit.”

Conversely, her friend Simon de Pury, chairman of art-auction house Phillips de Pury & Company, is happy to assert her place in the art world. “Jennifer breaks down boundaries. No one should box her in to food. She’s an artist, whatever medium she uses.” She planned a party celebrating his wedding last year.

But while she’s a masterful hands-on cook, her art is outsourced. “I was never interested in the hand of the artist,” she explains. Like many artists, she provides the idea and the specs, and a craftsperson executes the work. Rubell is aware of how that may strike people. “That’s been true since the Renaissance,” she says professorially, not defensively. “Artists have had factories for a really long time.”

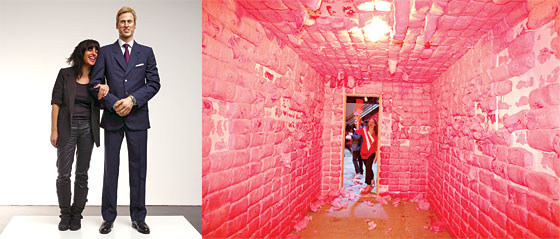

Her first solo show, “Engagement,” at the Stephen Friedman Gallery in London in February, addressed the issue of authorship while seizing upon an iconic moment in the making. The show featured a life-size wax-and-fiberglass sculpture of Prince William, made by sculptor Daniel Druet, with a replica of Kate Middleton’s diamond-and-sapphire engagement ring affixed to his forearm. Visitors were invited to step up next to the prince, slip their finger through the rock, and imagine the distinctly un-feminist thrill of being betrothed to royalty.

“I think we all grew up inside of feminism, feeling that not being okay. But the first time I slipped my finger through that ring, I felt giddy. It feels like, ‘Fuck you, I do want this,’ ” she says. Druet was credited with fabricating the statue, she explains, but “interaction is the thing that makes it a piece by me. And,” she says, laughing, “it was heavily interacted with.”

The show attracted international attention, including spots on morning talk shows here, where Rubell had the opportunity to discuss interactive art. But being largely under the critical radar so far has, she admits, been “a tremendous luxury, like being in art school, except being public.” That will likely change soon: This fall, starting in September, Rubell’s work will appear in five shows around the world, at Cal State–Fullerton; Fondation Beyeler in Basel, Switzerland; Perry Rubenstein Gallery in L.A.; Dallas Contemporary; and Performa 11 here in New York. She has been working with beekeepers on a series of honey paintings created by 50,000 bees. Another project is inspired by Studio 54’s drink tickets. In a way, her work can be seen as a valentine to Uncle Steve, the man she calls her “second father,” who did everything at Studio 54 “in order to have this ephemeral magical moment.” The club, to her mind, was “one of the great performance pieces that ever existed.”