A Cattelan Menagerie

The artist on some of his creations. (Slides 3, 4, and 6 are from the upcoming issue of Toilet Paper and have not been seen before.) Concept and realization by Cattelan/Ferrari.

Maurizio Cattelan’s first show in New York, in 1994, consisted of a self-portrait in the form of a live donkey wandering around a gallery under a chandelier, braying inconsolably. That show wasn’t up long—there were noise complaints—but even now, when his always-wry sculptures sell for millions and his unbelievably elaborate full-rotunda Guggenheim retrospective is about to open, he retains that same posture of self-suspicion. “Today I would say I don’t know how I arrived at this point,” he says, sitting on a bench near a playground on West 28th Street, not far from the West Chelsea galleries, cocking a knowing eyebrow at a sudden whiff of marijuana in the air.* “I don’t know how I arrived at this point, at the Guggenheim. There must be something wrong somewhere.”

But wrongness is everything to Cattelan: It seems to be what matters to him, and his sculptures, the most. Since the late nineties, and right through the art boom, he’s created a body of work that is pleasurably, or off-puttingly, wrong. It’s what any sensible person seeing pretty much anything he has ever created thinks: The baby elephant on this page dressed up like a Ku Klux Klan member? A sculpture of a squirrel sitting at the kitchen table, having killed himself? Three sweet-faced, life-size boys strung up by their necks from a tree branch? And—most famously—the statue of Pope John Paul II knocked to the ground by a meteorite. All are just wrong. A few years back, he and some friends even ran something they called the Wrong Gallery in Chelsea, which consisted of a locked glass doorway and one square meter of exhibit space.

Unsurprisingly, he has gotten a reputation as a prankster, the art world’s class clown. For years, he’d send his friend Massimiliano Gioni (who collaborated on Wrong with him and today is the top curator at the New Museum) to pretend to be him at lectures; they cheekily named another gallery they ran, in Berlin, Gagosian. And now there’s the Guggenheim retrospective itself, which Cattelan refused to do unless the museum agreed to dangle all of his very valuable sculptures from its ceilingby an enormous truss. (See page 4 for a look.) “You could describe the show as either salamis or toys,” Cattelan suggests. “It was the only way to do the show there,” he adds. “Actually, the building was forcing me to do this.”

Cattelan, 51, thinks of himself as an artist driven by these eccentric necessities. He grew up in Padua, where his father was a truck driver. His mother, a cleaning woman, suffered from cancer; Cattelan left school at 17 to help support his family. That suicide squirrel? It was sitting at a kitchen table just like the one in his parents’ house. “If you see just the surface of the work, it can be playful,” says Cattelan. “But sometimes it can be extremely sad.”

After lots of boring, dead-end jobs—including one at an actual mortuary—he became a furniture designer, which is how he makes art, too. He comes up with a concept, an image, to be fabricated by others. He describes what he does as digestion: He consumes images, and then, by logical extension, the art comes out the other end.

But the retrospective is also a way for Cattelan to quit making sculpture. It is in effect his retirement party. “You ever feel tired and want to change occupations?” he asks. “People have been asking for things for so long. If I was really making more works, I would have already. I don’t know … If you were in a band, you might feel you start to repeat yourself.” His art has become increasingly expensive (Untitled, a 2001 wax self-portrait—complete with real hair—of Cattelan sticking his head out of a hole in the floor, sold for $7.9 million last year), and with that need to make something “defendable and open to many readings,” as he puts it, there is a certain stress. Maybe it’s just not as much fun anymore, or it’s just no longer necessary, since he’s well past any danger of being trapped in the Italian working class. So he says he is planning to stop and let his archive take over. “There will be shows without my involvement. It will be as if I were dead. Technically, that is—instead of being dead and not seeing what people will do with your work, you will be alive and you will suffer a lot.”

*This article has been corrected to show that Cattelan no longer lives in Chelsea.

Even if he actually stops creating sculptures, he’s not going to stop digesting. He and his collaborators used to produce a magazine called Permanent Food, which was a sort of scrapbook made of other magazines. After a while, “we wanted to produce our own pictures,” he says, which led to starting Toilet Paper, a Dada-ish confection of staged scenes he creates with photographer Pierpaolo Ferrari. It is being paid for by the billionaire contemporary-art collector Dakis Joannou’s Deste Foundation, but at $12 a copy, it is a more democratic endeavor than sculpture. He actually wants people to see what he’s thought up; the reaction is what is most important to him. When his pope-hit-by-a-meteor piece, The Ninth Hour, was in Warsaw, several members of the Polish Parliament attempted to stand the wax John Paul up to give him back his dignity. A man in Milan was so disturbed by the garroted boys he climbed the tree and cut two of them down (before falling out of the tree himself).

On the bench, Cattelan flips through images planned for the newest Toilet Paper. “Probably they’re like advertising pictures, fitted out with meaning,” he says. “I won’t say I’m not fascinated by the way advertising works. I like the sleekness. But a picture in advertising doesn’t last too long. They have to work for 30 seconds. And I’d like to reach at least two minutes. This is my goal. To break that two-minute record.”

And despite his saying, “I never talk about my work as a joke,” he proceeds to make sardonic commentary on each image. There’s the photo of a woman crouching in pants with a heart-shaped hole in the back (“You can customize your own shorts”), and a museum engulfed in flames (“We needed some pictures with no people inside. This is of very expensive paintings set on fire.”) He becomes very animated talking about his homage to “Mike the headless chicken,” who “was so famous … alive for years without a head, fed with a dropper. The farmer was probably preparing dinner and left a little part of the brain by mistake. You can go on YouTube and see Mike walking among the other chickens.” When we get to one of a serious-faced woman holding a copy of a mocked-up newspaper with the headline NOW OR NEVER, he laughs and says, “This is a good one. It’s a motto for every day.” But perhaps his favorite is of a man with his feet inside fish heads. “We were after something else, and then a friend was around and started playing with them. He looks like he’scross-country skiing. It’s disturbing, I have to say. This is what I like, when it’s difficult to find what is going on, but it’s still a compelling picture.”

Not Afraid of Love, which sold for $2.7 million in 2004. Catellan expains: “We often end up kissing the wrong person goodnight.”Photo: Atitilio Maranzano, “Not Afraid of love,” 2000/Courtesy of Maurizio Cattelan

“Hi, I’m Miracle Mike, the headless chicken. A true story from the forties.”

“We had swordfish for dinner and took this picture with the leftovers.”

“I see a painter’s palette.”

“She was the animal trainer on the set of TP 4.”

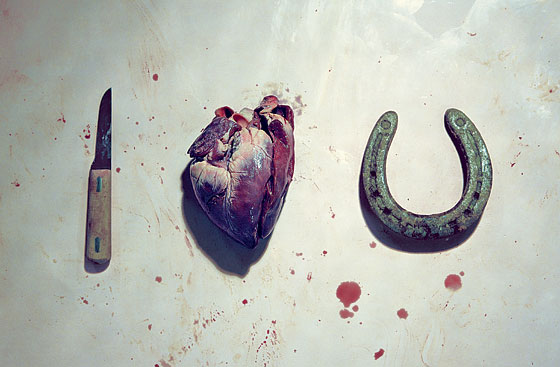

“We wanted to make an “I Love New York’ picture and ended up with this.”

“New York’s vermin gets smarter and smarter.”

“Third person who matches the tail to the animal get a free ticket to the Bronx Zoo!”

“There’s an old rumor that Walt Disney’s head is kept frozen somewhere in a cryogenics lab.”

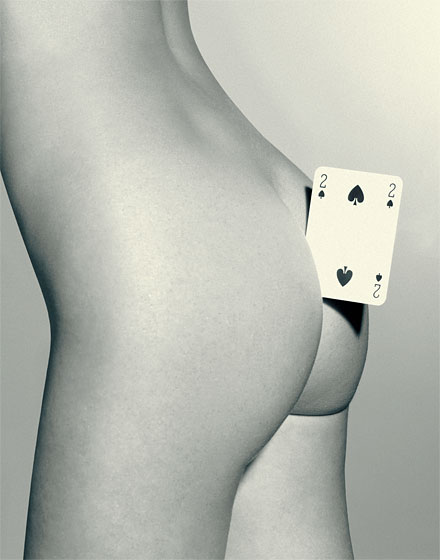

“The 2 of Spades has now become my favorite card.”

“This image has been on my wall for months and I still can’t figure it out.”

“Cute cat pictures are the most viral images on the internet.”

“I have this friend who looks just like a Paul McCarthy.”

“I was in the grocery store and thought of Yayoi Kusama.”

“We all had a bad teacher we loved.”

“The time is definitely now.”

“This is a TP tribute to Mario Sorrenti.”

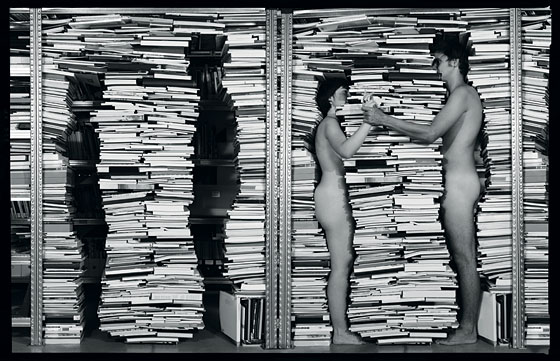

“Oh Marina, Marina, Marina.”

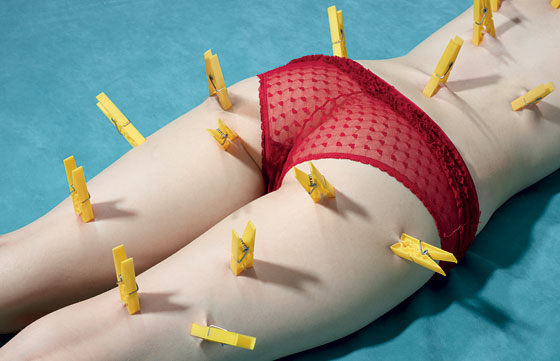

“This could be the perfect cover for a new edition of Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying.”