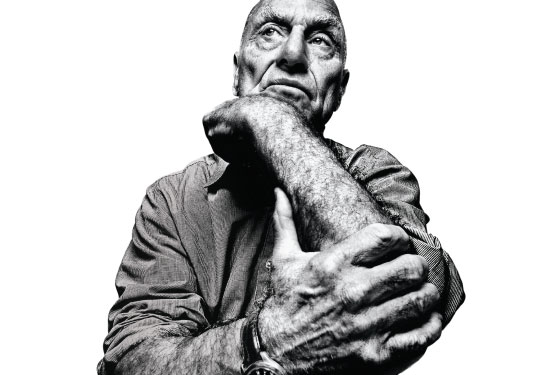

Richard Serra takes up a lot of space. Which is not to say that he’s a big guy—only about five-five, with a wiry build—but that he expands to fill the available room: pacing, gesturing, reaching for pencil and paper, and picking up, with swift strokes of graphite, where his words trail off.

His sculptures take up even more space, space that MoMA has never afforded them, until now. This month, three new works, incorporating several hundred tons of Cor-Ten steel, were hauled into the museum’s contemporary galleries in preparation for the retrospective “Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years,” opening June 3. Two more were hoisted by crane over the wall of the sculpture garden, and earlier works—smaller and lighter, but still formidable, made of lead and vulcanized rubber—will be shown on the sixth floor. The late curator Kirk Varnedoe specified, before MoMA’s renovation, that the floors in the contemporary galleries had to be built to support Serra’s art. He’s actually engineered into the building.

New York hasn’t always been so accommodating. In 1981, Serra’s notorious Tilted Arc, a 120-foot steel curve commissioned by the federal government, was installed at Federal Plaza. Workers complained that the sculpture blocked their view and shielded muggers; security personnel said it could serve as a blast wall for terrorist bombs; a judge claimed that it was exacerbating a rat problem. Serra insisted that the sculpture was site-specific and couldn’t be moved. After a public hearing and a legal battle, Tilted Arc was cut up in 1989 and carted off to a warehouse, where it remains. If he learned anything from the experience, Serra says, it’s that “the government has no use for art or artists.” He pauses. “I don’t think I helped myself, in terms of my personality. I didn’t understand the media.” (For a vintage example, take a look at Television Delivers People, a 1973 anti-corporate video screed now available on YouTube.) Certainly statements like “Art is not democratic. It is not for the people” rankled many New Yorkers, even as artists and critics rose to Serra’s defense. It didn’t help that his art had, indirectly, killed someone (a rigger, crushed to death in the early seventies). Sculpture was supposed to be an object in a gallery, something to be politely circumnavigated; Serra’s art swallowed you whole.

With this retrospective, the disconnect between the Serra loathed by the public and the Serra lauded by the art world may, finally, be history. It’s not that the combative artist has become softer or less difficult. But, in the past decade, our relationship to contemporary art has shifted. As Miami-Basel party crashers and MoMA’s many corporate sponsors can attest, work that used to be seen as an elitist diversion now counts as mass entertainment. (Think of Jeff Koons’s Puppy at Rockefeller Center.) Museums, in the midst of a steroidal building boom, are making room for Serra; two of the three new sculptures in the show are likely to go to a new wing at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Just as important, Serra developed an unusually rich body of work during the nineties, beginning with a series called “Torqued Ellipses”—a rare second act for a mature artist, especially for a sculptor of Serra’s generation. Successful peers Robert Smithson and Gordon Matta-Clark died young, and many others simply faded away.

Serra, born in San Francisco in 1939, came to New York in 1966, after attending UC Santa Barbara and Yale (he paid his tuition by working at steel mills). In New Haven, he was once kicked out of class for parodying Robert Rauschenberg with a live chicken on a pedestal. Living in a Greenwich Street loft, he thrived on the experimental scene. At one point, he started a moving company with Chuck Close, Philip Glass, Spalding Gray, and others. As he recently explained, “In those days, when someone sold out a show, they would say ‘too bad—the client knows what you’re doing.’ ”

By most accounts, Serra’s first big breakthrough was a 1969 performance-sculpture made with molten lead in a Harlem warehouse, sponsored by Leo Castelli. Critics called his splashings “ejaculations against the wall,” even though they were made painstakingly, by building up the lead gradually, spoonful by spoonful. Serra occupied an important niche between the sleek, inert minimalism of Donald Judd and Smithson’s messy earth art. The influential critics in the October gang hailed him for expanding the field of sculpture, taking it off the pedestal and making the viewer’s movement part of the experience.

It took decades for ordinary New Yorkers to recognize Serra’s contribution to sculpture, even after the Tilted Arc fiasco. The turning point was a 1997 exhibition at the Dia Art Foundation in Chelsea, showcasing a new body of work called the “Torqued Ellipses.” The forms, Serra says, were inspired by a misreading of the floor-and-ceiling ellipses in Borromini’s church San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome. Staring up at the ceiling from a side entrance, he wondered if an elliptical volume could be made to twist in elevation without changing its radius from top to bottom—without, that is, narrowing at one end like a flowerpot. Frank Gehry’s engineer told him it probably couldn’t be done, at least not in steel. Serra figured out a way, first making wobbly plywood models and rolling them up in sheets of lead. That’s typical of Serra’s weird relationship to architects: friendly, competitive, and occasionally disdainful. “Museums have to be as fluid as they can,” he says. “One of the problems is that architects are not.”

The first “Torqued Ellipse” took three years to make. By the time he was done, Dia had gained a new chairman, Leonard Riggio, who was sufficiently wowed to push for acquiring all three. (You can see them at Dia:Beacon.) Serra says that their warm reception surprised him. “I thought the first lead prop pieces I did were a breakthrough; I thought the splash piece was a breakthrough. But I think because people could enter into these pieces, my work became more accessible. They could walk in and find something that wasn’t in nature and wasn’t in architecture.”

Not in nature, not in architecture. Serra often uses these words to describe his art, defining it by what it isn’t, but after 9/11 the phrase acquired special resonance. That fall, Serra’s solo exhibition at Gagosian opened on October 18 (rescheduled from a month earlier, because the truckers had gone to work at ground zero). It was impossible to walk through his “Torqued Spirals” series without being reminded of that other twisted steel sculpture a few blocks down West Street. After negotiating a curved, narrowing passage, you suddenly found yourself in an open chamber, a metallic tang in the air.

For most of this decade, Gagosian and Dia were the only places in the city where you could see Serra’s large-scale sculptures. The largest and most significant site of his work is in Bilbao, Spain, where the Guggenheim mounted a permanent installation in 2005. Even against the flashy topology of Gehry’s architecture, Serra’s forms held their own; Robert Hughes said the work “dominates Gehry’s space like a rhinoceros in a parlour.” Serra might disagree. “Frank was a close friend of mine for about 25 years,” the artist says carefully, but the past tense is deliberate—the two had a big falling-out in 2001, after Serra told Charlie Rose, “I draw better in my sculpture than he draws in his architecture. Frank is parading right now, and so are all of these mouthpiece critics that, you know, support him as ‘The Artist.’ … Hogwash. Don’t believe it.” Today, Serra says of Gehry’s Guggenheim, “He built a very large shed that you couldn’t really partition. It didn’t function too well for other works of art; paintings kind of disappeared, or people just passed them by. People go there to see the building; if they happen to see my work, fine.”

MoMA’s retrospective was supposed to have been a joint project with Dia, before the foundation lost its space in Manhattan. “When Dia lost its real estate, I assumed I was just going to show three new pieces in the sculpture garden and that’s it,” says Serra. “[MoMA director Glenn] Lowry stepped up and said, We’ll take over.” The show is entirely devoted to sculpture; while sketching is a constant for Serra—during our talk, he reached for a pencil at least three times—he thinks of his drawings as “an autonomous body of work.” One, made with muscular strokes of black oil stick and depicting a hooded Abu Ghraib detainee below a scrawled STOP BUSH, was shown at the 2006 Whitney Biennial and spawned posters, and even a “Stop Serra” parody. “I didn’t think of that as an artwork. I was just pissed off,” he says. “And I’ll do it for the next election—probably for Obama and against Giuliani.”

Serra is still trying to make steel do things unprecedented in nature or architecture. “I actually taught the steel-producing industry to make forms they’d never dealt with before, and build machines they’d never built before to make them, which has helped them receive jobs in the aerospace industry,” he says. “We’ve come up together.” Band, a 72-foot serpentine ribbon, and the smaller and more subtle Torqued Torus Inversion, look simple enough in Serra’s quick sketches but become impossible to size up in elevation, the walls appearing to slant backward or forward with the minutest shift in the viewer’s position. The effect is especially spectacular in Sequence, a curlicued S that you enter on one side, emerging from another after negotiating a dizzying double spiral. “It’s almost like walking a Möbius strip—you get confused about what’s inside and outside,” the artist says.

Later, in the sculpture garden, Serra surveys the outdoor portion of the retrospective, and in the sun’s glare the brown steel looks almost like crushed velvet. “Cor-Ten steel is a time capsule. It oxidizes over eight to ten years, forms a skin, and then is permanent,” Serra says. You can see the difference between the two sculptures in the garden: Torqued Ellipse IV (1998) is younger than Intersection II (1992–1993), but it has a more uniform ruddiness; it was exposed to the elements while the older piece sat in storage. There’s a sign warning viewers not to touch, but not because the works are at risk of vandalism. Apparently, says Serra, small children running through the sculptures just can’t keep their hands off them.

WATCH THE VIDEO:

• Installation of Richard Serra’s Sculptures at MoMA