Appropriation is the idea that ate the art world. Go to any Chelsea gallery or international biennial and you’ll find it. It’s there in paintings of photographs, photographs of advertising, sculpture with ready-made objects, videos using already-existing film. After its hothouse incubation in the seventies, appropriation breathed important new life into art. This life flowered spectacularly over the decades—even if it’s now close to aesthetic kudzu.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “The Pictures Generation, 1974–1984” is less a critical survey of a highly influential aesthetic than a feel-good class reunion. Rather than opt for scholarship and tough choices, curator Douglas Eklund cultivated a gang’s-all-here coziness. It’s a huge show, with hundreds of objects, books, posters, films, and videos, and works by 30 artists. Had a museum outside New York originated a show this baggy, it’s doubtful that the Met would have had anything to do with it. (Though it’s fantastic that the fuddy-duddy Met is finally thinking about recent art. It needs to do so, more often and better.)

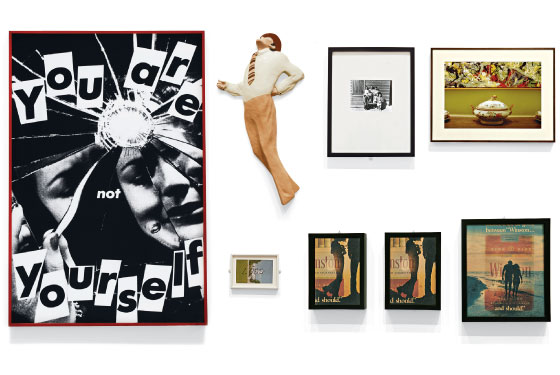

But if you do pick your way through this hodgepodge, you’ll find a spirited introduction to a lively moment. In the seventies, a group of American artists seized the means not of production but of reproduction. They tore apart visual culture at a time of no money, no market, and no one paying attention except other artists. Vietnam and Watergate had happened; everything in America was being questioned. In this charged atmosphere, artists braided together three recent styles. They made conceptual art more optical and snazzy. They returned narrative and figuration to minimalism while keeping the rigor. And rather than “liking things,” the way Warhol said Pop Art did, they were skeptical, especially regarding pop culture. This mix was laced with New Wave attitude, French theory, social consciousness, and raw material derived from everything from movies to logos. Pictures artists (as they were called) created a kind of anti- encyclopedia, looking at the world of representation and saying, “This is too good to be true.” They changed the way we look at images, ourselves, and the world.

Today, it’s hard to see two of the most radical things about Pictures art. First of all, most of it came out of photography. Back then, photographs were entirely separate from the elite fine arts such as painting (which was going through one of its near-death experiences). Even so-called fine-art photography was inexpensive and, by comparison, nearly disposable. It was certainly seen as a separate art with its own history and traditions, and critics and theoreticians didn’t much bother with it. The Pictures artists realized that photography could therefore be a theoretical free zone—that they could create their own approach there. Pictures artists staged their own images or copied or cut out others already in existence. The viewer took them in separately, in sometimes paradoxical waves: an original image, then the manipulations of it, then the places where image and idea intersected. This created a crucial perceptual glitch that irony and understanding filled. It makes Jack Goldstein’s footage of the roaring MGM lion someone’s take (and not necessarily his) on what the MGM lion stands for; Richard Prince’s Marlboro men went from familiar and bland to dangerous and funny; Cindy Sherman’s dressing up like a model became as strange as dressing up like a model really is. As participant James Welling observed, “Images compose our perceptions of the possible.” If widely reproduced pictures are often lies, artists, in Prince’s words, wanted to “turn the lie back on itself.” These artists did that with a vengeance.

Which brings us to the other, less visible radicalism of Pictures art: the great representation of women. Back then, it was instinctively understood that the doors of painting and sculpture were all but closed to them. In self-defense, women took up the devalued medium of photography, and much of their work breaks down the visual conventions of gender construction. They were feminists who didn’t want to be stuck in the “feminist art” ghetto, so they forged an art that was forceful, insistent, and seductive. Sarah Charlesworth tore up magazines to show us why we desired what we desired; Louise Lawler was a spy in the house of art, taking pictures of work by male artists installed in posh collections; Laurie Simmons created sicko domestic interiors; Barbara Kruger performed shock therapy on advertising; Sherrie Levine, who said, “Appropriation is not all that different from wanting to appropriate your father’s wife or your mother’s husband,” rephotographed famous photographs.

The criticism that grew up around Pictures art was authoritarian if almost unreadable, written in tight knots of language. Painting was called regressive, exhausted, mined-out; graffiti artists like Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat were written off as lightweights. Sometimes the Pictures artists fought with even their supporters. Adrian Piper (an artist on the fringe of the movement, left out of this show) wrote an open letter to critic Donald Kuspit saying that his writing “dehumanize[d] artists.” David Salle, whose work looks outstanding here, dismissed critic Craig Owens’s ideas about the way Salle “mystified information” as ludicrous.

Pictures art was never the feel-good fun portrayed here; it was influential, but it was also self-policing and insular. (Salle was essentially cast out of the inner circle for the sin of painting and for using photos of naked women—that’s how conservative the liberal art world was.) But it was a crackling time, and appropriation is too nice a word for how potent this style still is: Stealing and ransacking convey the atmosphere much better.

E-mail: jerry_saltz@newyorkmag.com.