As told to Michael Joseph Gross

“Martha did these gift baskets with, like, cookies and tea and stuff. And I said, ‘Could you make up one for Valentine’s Day for Andy?’

“She said, ‘Who’s Andy?’

“I said, ‘Andy Warhol.’

“She said, ‘He’s too old for you!’ And then she said, ‘Oh, I want to meet him!’ She brought the basket all the way down to New York herself, and she came to the Factory, and I introduced them, and they talked about Connecticut.”

—Richard Dupont

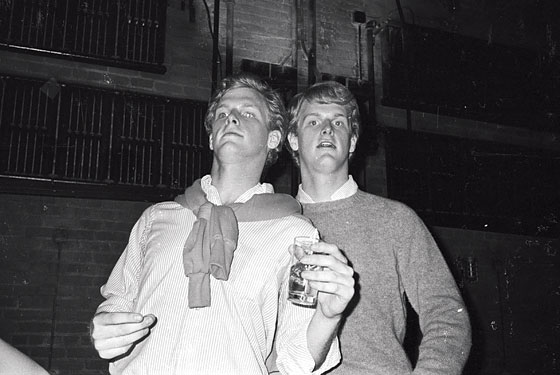

In 1977, in Westport, Connecticut, a pair of 17-year-old identical twins worked for a caterer named Martha Stewart. Tall, blond, and eager, Richard and Robert Lasko were high-school juniors who were adopted at birth by a couple who owned gas stations in Fairfield County. Their father left when the boys were in fifth grade, and aside from the occasional threat to “send them back to the orphanage,” their mother focused all her energy on finding a new man.

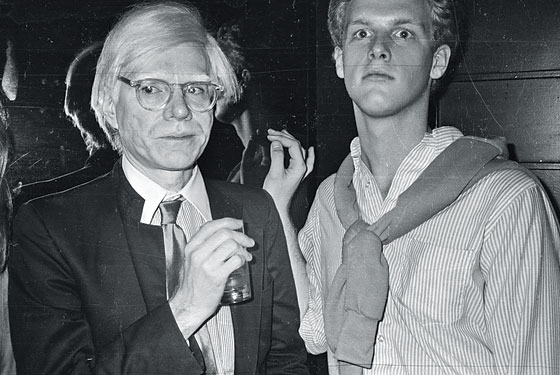

These were fast times, and they were fast kids. As teenagers, both of the twins experimented with drugs and sex, and wanted more of just about everything. One spring night, after working a Stewart-catered party in Manhattan, another of her employees took Richard and Robert to a new club called Studio 54. They found a world of excess even more immense than their appetites, and by autumn, the Laskos had run away from home, renamed themselves the Dupont twins, and become pets of café society. New York’s art crowd has never misbehaved more spectacularly than it did at Studio, and it didn’t take the boys long to find, at the center of the vortex, a new friend in the 48-year-old Andy Warhol. In their telling, the artist was both kind-hearted and grotesque, with Warhol and his set at their most predatory.

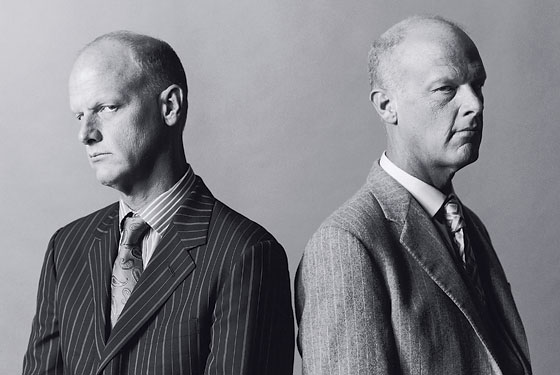

The twins, now 47 and sober, work as reporters for the social magazine Beverly Hills 213. Recently, in several interviews at the apartment they share in Beverly Hills, they recalled their lurid romp through New York’s last shameless binge of money, sex, and art.

Robert: I think we got into Studio 54 that first night because we were wearing the tails left over from catering the party. We had brought a 14-year-old boy from school with us, which made us the youngest people there, so everyone wanted to give us things and dance with us. I remember the smell: Halston Z-14 cologne, flowers, and poppers.

Richard: Hours went by, and we were having a great time. Someone offered us cocaine, which we had tried in Connecticut but felt completely new in New York. We lost our friend the minute we got there, but when we walked onto the dance floor, it felt like we had found a new piece of home. Our friend eventually found us hours later, and he was, like, “We all have to go to school tomorrow!” We didn’t get home until five in the morning. Oh my God. Martha called the next day because that boy’s parents were furious. She was concerned.

But over the next few weeks, Studio 54 became our lives. It felt so much more right than anything we had seen in Fairfield. And the people we met invited us into their family. I remember asking one of Steve Rubell’s assistants how many people were at the club, thinking there were three or four hundred. I couldn’t believe it when she told me there were over a thousand. It felt like we were family in Steve Rubell’s living room.

Robert: The third time we went, I met this guy named Rupert Smith. He came up to me at the main bar and offered me some cocaine, and then he invited me up to the balcony, all the way to the top. And then we had sex right there at Studio—I was nervous, but Rupert was really sweet about it. Afterwards, I said I was still in school working for this caterer, and he said he worked as a silk-screener for an artist named Andy Warhol. He asked if I had any brothers and sisters—you know, the usual conversation—and when I told him about Richard, he said, “Oh, you’re a twin? Andy loves twins.”

We went home to Rupert’s place, and at ten the next morning Rupert took me to the Factory. Paloma Picasso was there. When Andy came out and said, “You must be Robert,” I thought it was so nice that Rupert had called to say he was bringing me.

“When am I going to meet your twin brother?” was the first thing Andy asked.

Then he showed me some portraits he was doing, as if he was trying to get me to buy one. That was funny. Like I could afford one.

When we left, I called Richard and told him I would stay in New York for a while. I didn’t go back. And that’s why I got incompletes at school.

Robert: Holly Woodlawn, one of Andy’s superstars, said we had to have a famous name. And I thought that was a good idea, because what if our names got in the paper? I didn’t want everybody in Fairfield to figure out that we were gay. So one time when I was on a train in Fairfield, I saw a sign for DuPont, and I just thought it sounded right.

Richard: Andy told Robert, “Bring your brother into the city, and we’ll have dinner out at Regine’s.” So one day we showed up, and there was Diana Ross, Liza Minnelli, Mick Jagger. Oh my God. I adore Diana Ross. And Mick Jagger. I couldn’t believe that I was sitting with these people, and that they all wanted to meet me. They were there for Andy, of course, but I didn’t know it at the time. All I knew was that Regine’s had a tiny dance floor, and there I was, dancing with Diana and Liza. Andy introduced us as the du Pont twins from the Delaware family. We said we were from Connecticut. Everybody laughed.

I was excited to meet Andy because I heard that his boyfriend, Jed Johnson, was a twin. I wanted Andy to like me. I later read in his diaries that the publicist Susan Blond had told Andy that I was in love with him. His response was mean: “All I do is hold his hand and feel him up.”

When I read that, I was like, No! It was more than that. He would kiss me, and yes he touched me—he would sometimes jerk me off—but I think he did genuinely like me. Brigid Berlin, who was the receptionist and gatekeeper at the Factory, says so.

He said he worked as a silk-screener for an artist named Andy Warhol. When I told him about Richard, he said, “Oh, you’re a twin? Andy loves twins.”

I mean, I did piss on his “Piss” paintings, but that was later, and he wanted me to. I would bring cute friends of mine, and Andy would watch. He didn’t touch himself, but he did this moaning. “Oh!…Oh!…” It was like he was having an orgasm while he watched us. Or at least faking one. And then he would take us to lunch and give us $100, or some of his silk-screen wallpaper of the cow or of Mao.

Robert: At the end of a night out with Andy, we would say, “Good night, Andy,” and give him a hug or a kiss. He would ask, “Are you okay tonight?” We would say, “Oh, I don’t know…” And he would give us each $100.

Richard: Like in Breakfast at Tiffany’s—

Robert: —where she says, “Any gentleman will give a girl $50 for the powder room…”

Richard: And he always had an Altoids tin full of quaaludes that people had given him hoping to hang out with him, so he would give them to us too.

One day, Andy asked both of us and Rupert to lunch at Quo Vadis off Madison Avenue. He was thinking about putting pictures of us in Interview, but after lunch he told us he didn’t want to anymore. He said, “It’s not that I don’t like you, but Joanne du Pont said that you’re not du Ponts. Who are you?” When we told Andy and Rupert why we changed our name and how Robert came up with it, he said, “A lot of my superstars changed their names. Holly Woodlawn took the name of a cemetery.” Which obviously we knew, but we didn’t say that.

Robert: Andy always wanted to know everything about what Rupert and I did in bed together. Later he wanted to know everything about every man that Richard or I slept with. He would ask, “Was he ugly?” “Did you fuck him?” “What’s his apartment like?” “Does he have any money?” “Did he buy you anything?” “What secrets did he tell you?”

Richard: He’d always be trying to get us to help him get commissions for portraits. At Studio, he’d ask, “Can we get one of those rich men you’re sleeping with to buy a portrait?” And later it was more like, “Why don’t you go sleep with that one, and then talk him into getting a portrait.” We did that a lot.

Men would give us gifts like Cartier lighters and David Webb cuff links, and when I showed them to Andy, he would take them away from me. “You’ll lose them,” he’d say. Later, when I asked him what he did with all those things, he couldn’t remember.

Andy liked porno, and he liked porno stars. On Monday nights, when Studio was closed, we would go to this discothèque called the Ice Palace on 57th Street that was full of prostitutes and porno stars. I remember meeting two of them, and Andy saying, “You and your brother should do it with them.” Even the thought of doing it with Robert—in the same bed with my brother—God no!

Robert: We always said no when Andy asked to film us having sex or pose naked. “You’ll be famous,” he always said. “You’ll be a star. We’ll make a movie.”

Richard: There’s one afternoon in 1979 I’ll never forget. It was winter, and Andy’s “Shadows” paintings were up. He, Rupert, Robert, and I went to lunch on Canal Street, and this short man came and joined us. After lunch, it felt like I’d had six drinks instead of one. I must have been drugged.

Robert: Me too.

Richard: We went to this loft with high windows.

Robert: It was all white and very sterile.

Richard: And there was a bed. Somebody started to unbutton my clothes. And there was a video camera there. The short man wanted Robert and me to do it together. Andy was watching.

Richard: I was like, What the hell? What’s the scene, Dean? I said, “No! This is freaky!” And I just stormed out. Andy followed. Two blocks away, Andy went into a store and bought me a down coat from Japan.

Robert: He felt guilty and he bought us something.

Richard: One night when I was dating Egon Von Furstenberg, we were at Studio and Truman Capote was in the D.J. booth, like always. Egon’s friends laughed and said to me, “Why don’t you go tell Truman he’s a tired old queen?” So I did. I was a kid, and I’d do anything an adult told me to—especially when there were drugs involved.

One night we were at studio and Truman Capote was in the D.J. booth, like always. Egon Von Furstenberg’s friends laughed and said to me, “Why don’t you go tell Truman he’s a tired old queen?”

Some days went by. Andy took me to this party at Truman’s house, but I didn’t know where we were going. When we got to the door, Truman saw me and said, “Uh-uh. You’re not coming in here.” He told Andy what happened, and Andy made me apologize.

After that, Truman became a friend. I drank with him at Studio and went to lunch with him at La Petite Marmite and to dinner parties at his apartment at U.N. Plaza. I remember once sitting with a plate of cocaine on my lap, facing the Pepsi-Cola sign on the other side of the river. I was looking at the clock, waiting for Bloomingdale’s to open so I could get out of there and go somewhere—anywhere—or go to the train.

I don’t remember much of what Truman said to me that night, but he did say, “Stick with the winners.” He told me that our debutante friend Cornelia Guest was a winner.

I only realized much later where he got the phrase. “Stick with the winners” is what people say in AA.

Robert: I had become friends with Halston over the years, and one night, while we were all high at Studio, I saw Halston in the balcony. He invited me over, and after giving me some more coke he asked me to go home with him. I remember not knowing what to do, so I asked someone—I don’t know who—if I should. That person said yes, so I did.

It was winter, and I didn’t have a coat on, and I was freezing. When we got back to his house, we sat in the living room and did more coke. His boyfriend, Victor Hugo, and the house man, Mohammed, were both there. Halston left the room and went upstairs to his greenhouse to do something about the orchids.

Sitting on the sofa, I could see another guy walking around upstairs. He called me up and invited me to do a three-way with him and Halston. It was wild! But then Halston wanted to be alone with the guy, so I slept in Bianca’s room (she was out that night).

In the morning, I went downstairs and Mohammed cooked something. Halston said I needed a coat, and he gave me a black cashmere one of his. It was so beautiful—a big, long, one-of-a-kind coat that I wore to death at Studio. I lent it to this friend of mine named Milan, one of our only friends from those days who’s still alive, and I never got it back.

Richard: Andy brought us to dinner one Sunday with Salvador Dalí at the Versailles Room at the St. Regis. Dalí always had these dinners, and there were always a lot of drag queens. One named Potassa would be wearing a beautiful gown from Oscar de la Renta or Halston, and she would run around with a big bottle of Champagne and say, “Cham-pan-ya!” After we met her, she would always let us know when Dalí was in town and invite us for these dinners. Sometimes Andy wouldn’t be invited, which would make him upset.

Robert: One Easter, we were living at the Holiday Inn on 57th Street because they had a swimming pool and we liked to swim. We went to Crisco Disco after Studio, and when we came home, there was a plug in the keyhole to our door. It turned out we hadn’t paid the phone bill. What were we going to do? It was raining. So we called up Dalí, and he put us up at the St. Regis.

Richard: Sometimes we’d be in the back of the limo, and Dalí and Potassa would say, “Pull it out, pull it out!” Dalí had a word for orgasm—I don’t remember it, but he would say it and I would do it. I don’t know why. Maybe I felt like I had to in order to get invited to dinner or something. I remember doing it for Andy in the balcony at Studio, and in the back at the Factory.

One time I did it for Andy and Dalí together. We were in a black limousine, going uptown on Park Avenue South. Potassa and Dalí’s wife, Gala, were there, too. I don’t know why Andy grabbed me; maybe he was trying to get Dalí turned on, or maybe he just wanted to show that he had control. At first I was scared. But Potassa was pouring her Champagne and saying, “Cham-pan-ya!,” and Andy was saying, “Do it, do it!” so I just did. Gala was laughing, and Potassa was clapping. It was like theater for them, I guess.

Robert: After I broke up with Rupert, I started dating Fred Hughes, who was president of Andy Warhol Enterprises. He was such a gentleman. He had real style, and wore Penhaligon’s, and Lobb shoes. One night after leaving Xenon and walking Diana Vreeland to a cab, a bunch of us went back to Fred’s house, including the singer of a well-known rock band, and a beautiful, blond freshman at Columbia.

When we got to Fred’s, everybody went upstairs to do coke. You know, things happen even with straight guys when they do a bunch of drugs. Everyone was fooling around, and they all wanted to get in the freshman boy’s pants. He started to freak out, so I said, “Let’s go.” Maybe I grabbed him and got him out of there because I was thinking, “Who wants to be fucked up like I am? Surrounded by all these crazy people.”

Richard: In November 1978, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis threw a party for John Jr.’s 18th birthday and Caroline’s 21st at Le Club on East 55th Street. Patrick Shields, the manager, had introduced John Jr. to Robert and me at Studio 54.

John asked me if I was having a good time, and I said it was a great party.

“Has Andy introduced you to Mick Jagger?”

“Yeah,” I said, “I had lunch with him at the Factory last week.”

Then John asked if I had ever been to Winterthur, the du Pont mansion in Delaware. I said that we don’t speak to our family (which was true!) and changed the subject.

When I talked to Mrs. Onassis, she asked, “How is Andy?”

I said he was fine, and she asked, “Who are your parents? Are they here in New York?”

I said no.

She asked where I was going to college. Every time I saw her, she was full of questions like that: Do you have a job? Where are you going to school? Martha always asked us that, too. I never knew how to answer. I told Mrs. Onassis I was trying to decide what to do with my life and I would probably study the arts.

She said, “Well, you should learn a lot from Andy and the Warhol crowd.”

When Mrs. Onassis left Le Club, everyone got wild on the dance floor and started necking on the sofas. As we were leaving, one of John’s friends tried to push the paparazzi away, and there was a scuffle. John ended up lying flat on his back in the gutter while all the photographers snapped away.

Andy was upset that John hadn’t invited him to the birthday bash. The next day, he showed us the newspapers with John on the front page in the gutter. “How awful,” Andy said, and then the questions just spilled out of him. “Who was there? Did you talk to Jackie?”

Robert: Whenever he left Studio early, Andy would bombard us the next day with questions about who came later and what happened.

Richard: The questions would go on and on. Who did I see? What went on at Halston’s and Fred’s? Who was sitting with who?

Robert: Then he would get on the phone and start gossiping about the night, saying things like, “The twins know a little bit about everyone. They’re like Hedda and Louella. They’re like Elsa Maxwell.”

Richard: When you think about it, it was all bullshit. There was no meaning at all in anything that was ever said. Andy never wondered what was going to happen to us. Once, when I thought I should be an artist, Andy suggested I get a book together. He said, “I’ll give you some of my little drawings to put in your portfolio and submit them to school. You could get in.”

There are things I regret. But at the same time, a lot of the things that make me angry to remember are the things that I enjoyed too. I went along with it all, playing the game and having fun. I was not chewed up and spit out by any of these people—if I didn’t like them, I always could have left.

And besides, New York isn’t the same without Andy. A party wasn’t a party unless he was at the party. You felt great being with him. At least most of the time.

Richard: One day near Christmas, I called Martha and asked if I could go back to work for her. I needed money to buy presents and pay bills. So she let me work this party for Giorgio Armani at the men’s department at Barneys.

Martha liked to have us in the kitchen to keep her company and tell her stories and jokes. She also didn’t want us on the floor passing out hors d’oeuvre because she said we were too familiar with the guests. But she let us out of the kitchen this time, and when I went out, I saw Andy.

“We’re going to Studio afterwards,” he said. “You want to come?”

And I said, “Martha—we’re leaving!”

I can’t remember what happened later that night. Martha got mad that we were leaving. I remember that.