As head of Yale’s graduate photography department since 1979, Tod Papageorge is known by his students and pretty much anybody else he comes in contact with for his Old Testament level of crabbiness. He says things like, “Your work looks like it was made by someone who has never read a book.” There’s the persistent rumor that he once pitched a chair at one student out of frustration with the kid’s creative intransigence (he says he doesn’t remember this). But many of those who survived his withering critiques, and benefited from them, have gone on to be some of the biggest names in the art-photography boom we’re in.

Not that Papageorge seems entirely happy for them. Art stardom, and the facile mechanisms that generate it, seems to be just one more thing that makes him grumpy. But then again, at 66, he’s never had his turn in the Chelsea limelight. His last solo show was in 1985. Even his work is out of another era. The market cheers on lavish, color photographs of staged scenarios that imitate the portentousness of epic painting.He’s a black-and-white documentary photographer, trolling for, as Henri Cartier- Bresson put it, the “decisive moment.” He shoots people in the park or on the street.

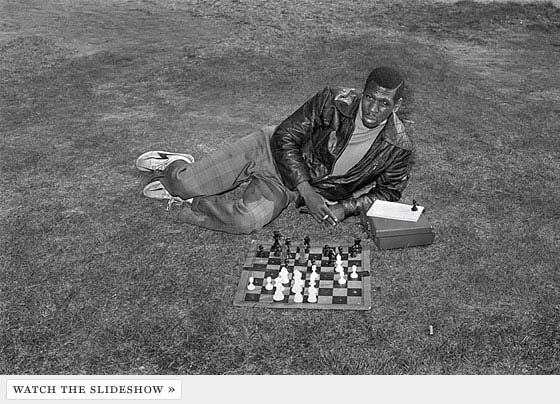

This week, Papageorge is having perhaps the decisive moment of his career. Pace/MacGill is opening a show of “Passing Through Eden—Photographs of Central Park.” There will be a book by Steidl, too. The pictures, which were taken mostly in the seventies, are a reminder of a city that doesn’t exist anymore, a grittier, less baroque, possibly more honest place. There’s something both beguiling and elegiac about them. This winter, Aperture will publish American Sports, 1970, or How We Spent the War in Vietnam. It’s a long-dormant document of his travels to football and baseball games.

So what took so long? “Nobody called,” he says. He also admits that “I have this reputation of being sort of a difficult case.” And later, by e-mail, he adds, “While I realize that, to some degree, I’ve deferred promoting myself for perhaps a small (and uninteresting) subset of psychological reasons, I really feel that the major reason for my ‘re-appearance’ has more to do with luck and timing.” He may be hard on other people, but you get the idea that his self- critiques are at least as withering.

Papageorge decided to become a photographer after encountering the work of Cartier-Bresson during his last semester as an English major at the University of New Hampshire. In 1965, he moved to New York, where he and his then-wife lived comfortably, he says, on about $3,000 a year, which he earned working part time copying patient records for an ambulance-chasing lawyer. He’d use a primitive portable copier. It often overheated.

He quickly found his way into a group of artists who helped redefine the medium. Perhaps the most important one was Garry Winogrand, who held photography salons in his apartment. “It was amazing,” remembers Papageorge. “I mean, to go to his house every Sunday night and have Garry think about photography like Socrates.” One of Winogrand’s pronouncements was, “I photograph to see what the world looks like in photographs,” which had a particular effect on Papageorge.

The pair, along with another young photographer, Joel Meyerowitz, became inseparable. They’d shoot on Fifth Avenue several days a week, often ending up at the MoMA Café, where they would drink 25-cent coffee and argue. “We were feeling the grandeur of this little medium,” Meyerowitz says. “And Tod was the most intellectual of us.” It was a heady time for photography. In 1967, John Szarkowski, the director of photography at MoMA, mounted the “New Documents” show, which included the work of Lee Friedlander, Winogrand, and Diane Arbus. The exhibition “removed [photography] from the arena of being a photojournalistic exercise and put it into the context of fine art,” says Joshua Holdeman of Christie’s.

Of course, most photographers still weren’t being collected. “It was a time when there was no value in photography,” Meyerowitz says. “No market.” Meanwhile, Papageorge started teaching, at Harvard and MIT and then Yale, whose program had been run by Walker Evans until his death in 1975. He became boss, and within two years of his arrival, Papageorge had replaced the entire staff. Yale’s became arguably the most important program in the country. There is hardly a major American photographer who has not been a part of it, either as a regular critique panelist (Joel Sternfeld, Michael Spano, James Casebere, Collier Schorr, Laurie Simmons) or as a student (Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Gregory Crewdson, An-My Lê, John Pilson, Justine Kurland). “Tod’s voice is still what I hear in my head when I’m photographing,” admits Kurland. It’s not always a nice voice: “He was a bastard, and he did not like my work in any way,” says DiCorcia. Nor a progressive one: He long resisted color film.

His rigor, and likely his fury, seems to be grounded in an almost poetic understanding of what the photo can do. “One of my attractions to photography was that I felt it was much closer to writing and literature than any other visual art,” he says. With the Passing Through Eden book, “I started trying to sequence it according to Genesis. I had my Adam and my Eve. It sounds foolish—in a way, it is foolish.”

Ultimately, Papageorge’s most inadvertently influential move at Yale may have been the hiring, in 1993, of Gregory Crewdson, a successful creature of the art world. In 1999, Crewdson co-curated a show, “Another Girl, Another Planet,” of young female photographers whose staged pictures of adolescent girls emphasized crises of identity. These artists became known as the Yale Girls. The subject makes Papageorge a bit sarcastic. “I have a vague memory of the Yale Girls,” he says. “They’re all talented, ambitious, and good-looking. It had less to do with pictures than the pictures that might be made of the people who made the pictures.”

Papageorge is just happy to be getting the recognition he has awaited for so long. The prosperousness of the larger art market, and its hunger for something new, even if it’s old, has inspired a rediscovery of him and his peers. In 2002, the International Center of Photography mounted a show of Winogrand’s work. In 2005, MoMA did a definitive Friedlander exhibit, while P.S. 1 mounted one of Stephen Shore’s work. ICP will have a Shore show this spring. The auction houses are following suit.

“The reassessment of that period has enabled this review of Tod’s career,” says DiCorcia. “It’s not just because someone got to the P section of forgotten photographers … Tod’s a logical choice, and the work is good.” For the Pace/MacGill show, Papageorge’s photos are being priced at $5,000, in (rather large) editions of twenty. They’re printed bigger than they could have been in the seventies, making them more precious and paintinglike.

And he’s still testy. “The fact is that anyone could have called any day during the interim and nobody did,” he says. “The work was always there. All it took was one person to say, ‘I’ll do this for you, Tod.’”

Passing Through Eden—Photographs of Central Park

Pace/MacGill Gallery. Opens April 3.