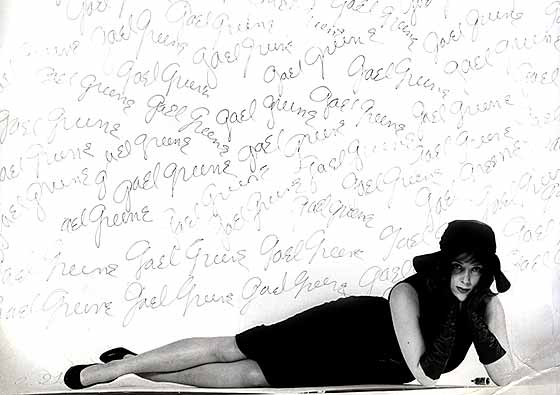

1. ELVIS

Elvis Presley was coming to town to do two shows at Olympia Stadium. At 21, I was one of the hormone-raging millions with a crush on Elvis—the young, beautiful, seemingly unspoiled Elvis.

No New York newspaper would hire me fresh from college in 1956—I had applied everywhere and sent countless résumés—so I was languishing at home in Detroit, Michigan, the most junior staffer at United Press International. I wrote a letter to Colonel Parker, asking if I could spend the day with Elvis and write about it. I got back a mimeographed invitation to Presley’s official press conference. I was insulted and frustrated but not discouraged.

I wore a simple body-skimming black shantung dress (my most slenderizing) with white stitching along the neck and cap sleeves, shiny black patent-leather pumps, and little white kid gloves. I arrived backstage early to study security and find its most vulnerable link. Lamar was his name. He was in charge of guarding the door and a pair of 24-karat-gold pants with a sequined stripe, which he carried in a padlocked garment bag. From his rolling drawl, I figured he must be one of Elvis’s Memphis mafia.

“Do you sing, too?” I asked, tickling his tweed elbow. At that moment, a slim figure in a red suede cloth jacket was slipped into the room by a phalanx of uniformed security guards. Elvis curled his lip, smiled, and flicked back his shiny black cowlick, then seated himself on the edge of a table with an “I’m all yours” wink. He was looking right at me. I felt weak, and I blushed all over. Then, after gamely responding to our lame and predictable queries, too quickly Elvis was gone.

Lamar took my hand. “If you want to stand close by, you can watch the show from the nearest aisle and slip back here before the crush at the end. Then you can go to the hotel with us to hang out and have a coke between shows,” he offered. I stood silent in the hysteria of screams. Suddenly Lamar grabbed my hand and tucked me into a limo with an assortment of silent young louts, the full Memphis crew. We pulled out of the underground bay.

“But where is Elvis?” I cried.

“He’s behind us in a taxi,” Lamar promised.At the Book-Cadillac Hotel, there was a volatile coagula of fans waiting to catch a glimpse of Elvis. Upstairs in a 24th-floor suite, the Memphis cronies sipped their cola and divvied up the comics from the Sunday papers. Nobody looked at me. I was too familiar, an offering for the King.

Oh dear heaven. I stopped breathing. Elvis. He stood in the door, smaller than life—small in life, I mean—pompadoured hair slick. He sized up the room and astutely realized I was the only female in it. He slunk directly toward me, slender in shiny black faille trousers and a sheer blue short-sleeved eyelet organdy shirt, till one leg was brushing my thigh.

“And who are you?”

I babbled something.

He didn’t seem to be listening. Silently, he took my hand—yes, still gloved—and led me to a bedroom. I was thinking, Oh my God … this is Elvis… . I am going to do it with Elvis. I am not going to be coy. I will not make him talk me into it. He didn’t ask. I didn’t answer. He closed the door, dropped his pants, and lay on the bed—very pale, soft, young—watching me take off my clothes and, yes, at last, my little white gloves. All the way up on the 24th floor, I could hear the girls chanting on the street below: “We want Elvis. We want Elvis.”

And look who has him, I was thinking. I think it was good. I don’t remember the essential details. It was certainly good enough. I know the reality of it was thrilling beyond anything I might have imagined.

“I need to sleep now,” he said when it was over.

I grabbed my clothes and fled into the bathroom to dress. As I picked up my purse, wondering if a good-bye kiss would be appropriate, Elvis opened his eyes, blinked, as if he wasn’t sure for a moment what I was doing there.

He twitched a shoulder toward the phone. “Would you mind calling room service and ordering me a fried-egg sandwich?”

The fried-egg sandwich—that part I remember. At that moment, it might have been clear I was born to be a restaurant critic. I just didn’t know it yet.

2. HENRICraig Claiborne was a god, my hero, my idol. Even non-food-obsessed New Yorkers looked to his Friday restaurant review in the New York Times as gospel. His favorite restaurant was Le Pavillon, creation of the quintessential Henri Soulé. I just didn’t have the courage to walk up unknown and unrecommended to the legendary martinet at his podium as he rationed out the royal banquettes at Le Pavillon. I knew from reading Women’s Wear Daily and Joseph Wechsberg’s Dining at the Pavillon how his glance could turn a poseur to fleur de sel. Finally, I realized the way to reach Monsieur Soulé was through my typewriter. I had started freelancing so that our fancy eating would be tax-deductible. I proposed a story to Ladies’ Home Journal: “A Week in the Kitchen of the Pavillon.” Henri Soulé, a flirtatious five-foot-five cube of amiability, was willing. Pouting and posing, an owl who saw himself as an osprey, he instructed his chef, Clément Grangier, to suffer me in the kitchen below for as long as required. I arrived each morning in my tennis shoes, was taught how to flute a mushroom, watched Chef Grangier whisk butter to order for a fussy habitué, marveled at the saucier’s iron right forearm, and took lessons in quenelles de brochet—the delicate whipped pike-and-cream dumplings that were my favorite dish.

One Friday, Soulé invited me to lunch at three o’clock. “Say you want les tripes à la mode de Caen,” he commanded. “It’s forbidden by my doctor. That damn Grangier won’t even serve it to me.” He instructed Chef Grangier to hand-chop his usual hamburger. When our food had been dished up from the copper casseroles, and the captain and waiter had backed away in respectful obeisance, Soulé switched plates, generously allotting me a plop of tripe alongside my burger.

I stared at the tripe, a scary nest of anatomical parts in a muddy sauce. It would be a while before my aversion to tripe would evolve into a passion for tripe in all its guises. I speared the tiniest nubbin on my fork, doused it with sauce, and swallowed it whole. “Hmmm,” I said.

Soulé looked up, fork balanced en route to his mouth. “So you are writing about the secrets of Le Pavillon. You won’t find the secret of Le Pavillon in the kitchen,” he said. “The secret of Le Pavillon … c’est moi.”

He puffed up his pouter-pigeon chest. “Le Pavillon, c’est moi.”

When Soulé was preparing to reopen La Cote Basque, my husband, Don Forst, encouraged me to offer the story to Clay Felker, an editor at New York, the Herald Tribune’s Sunday magazine. My docudrama of the countdown to the celebrity-riddled opening lunch was important, Soulé told me later: “The Trib … that means something to Soulé. Now you must come often. This is your home.”

He lighted up a cigar. I lighted up a cigar. We puffed away.

“I love a woman who smokes cigars,” he had said.

I never really liked that awful cigar taste in my mouth. I gave them up after a few months because I didn’t want to smell like my uncle Max. But I loved those gossipy lunches, the unfolding intrigue of the Food Establishment, Monsieur Soulé’s indiscreet confessions. The lies certain people told to get a reservation when Soulé insisted he was booked. The cosmetic titan who would stop short and refuse to budge if Soulé tried to lead him to a table beyond a certain line in the carpet. The great beauty who had so much to say to her walker and nothing to say to her husband. That’s how it was in the fall of 1968, when Felker beckoned me to the new New York. I had one foot in my kitchen and a finger already in the Manhattan dining stew.

3. CLINT Clint Eastwood had been working all day in the Mexican desert when I arrived on the set of Two Mules for Sister Sara, delegated by Helen Gurley Brown in 1969 to profile the charismatic cowboy. I felt awkward, too dressed for the desert dust, intimidated by being that close to a movie star. His manginess, the unkempt hair under his flat-topped leather sombrero, the sweaty rubble of beard, and a mangled stub of a cheroot clenched in his teeth dimmed his unbearable good looks, but not much. He seemed to be cashing in on the silent anti-hero image of the spaghetti Westerns that had rescued him from Hollywood’s indifference.

“At least it’s me doing my own bag and not someone trying to imitate me,” he said, defending himself when I asked.

Between scenes, he stripped off his shirt. His jeans rode low on bony hips. The man was clearly not into food. Six foot four of skinniness, he lay collapsed on a canvas chaise, silently stroking a baby rabbit, unwound, obviously content. Everyone I had interviewed in preparation for meeting him had alerted me: “He loves animals; he has a gentle reverence toward animals.” I interpreted this to mean animals are easier than people, especially nosy women with notebooks and tape recorders.

Suddenly, there was a commotion behind his trailer. Some locals had roped an iguana and were dragging it to the prop tent in hopes of cashing in. Clint recoiled. “I sometimes wonder who is the zoo. The animals or the people,” he said. He disappeared, returning with the writhing iguana, getting slashed by its whiplash tail.

“I bought it for five pesos,” he said, hitching the beast to an awning stake. “What do you think they eat?” After lunch, while setting the beast free, he backed into a cactus. The makeup crew was still plucking quills from his back when I hitched a ride back to the hotel.

I could see the man was exhausted by the time we met for dinner on the terrace in near darkness at Hacienda Cocoyoc, the resort where the stars were lodged. The terrace was not lighted, to discourage mosquitoes, I supposed. I wrestled in darkness with the pork chop I’d foolishly ordered. One bite told me it was almost raw. Clint tossed most of his food to the dogs ringing the terrace. I quickly got rid of my chop, too. I kept trying to draw him out. Nothing I asked provoked an insight, or even more than a bored response.

I wasn’t any more comfortable in this charade than he was. But he wasn’t giving up yet. I got the message that he had committed to this interview to lure millions of Cosmo girls to see his movie. I followed him back to his suite, where he stretched out on the sofa and glowered at my tape recorder. I asked a question. He didn’t answer. I looked up from the notebook. He was asleep.

I’d never had anyone fall asleep in the middle of an interview before. Engelbert Humperdinck had been late and rude, so I said, “Forget it,” and walked out. But Eastwood had been unfailingly polite. I touched his arm to wake him.

“Let’s go to bed,” he said.

I guessed he would do anything to escape talking. I realized that I absolutely did not care about his motivation.

Afterward, he started to talk. I didn’t say a word, for fear of stopping him. He answered questions I wouldn’t have dared ask.

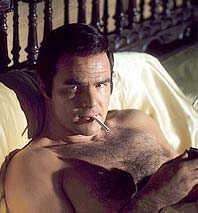

4. BURTBurt Reynolds was filming White Lightning in the stifling heat of Little Rock in August 1972, when Cosmopolitan sent me off to pin him wiggling to the canvas. One year earlier, the buzz about Reynolds’s powerful performance in Deliverance was so feverish, it had made him nervous. If the picture lived up to the hype, it would be a breakthrough for the actor, who’d been fired from Universal and had slogged through television action series—Riverboat, Gunsmoke, Hawk—only to find an audience by being himself, sardonic and self-mockingly funny, on the late-night talk shows. Then came the Cosmopolitan centerfold. Burt had astonished himself and the world by posing nude on a fur rug. From the clips and quotes, he struck me as a man who didn’t give a damn what anyone might think.

I found Reynolds in the Sam Peck Hotel bar with a string of locals warming the bar stools and the imported movie talent cooling down after a day on the set. He was big as life, which is never as big as celluloid or fantasy, looking fresh-scrubbed and Saturday Night Feverish in a skintight striped body shirt open at the neck and lean black stretch pants.

This was work for both of us. But the rules of this movie-star-interview game say you both pretend it’s fun. In those first few minutes, his leg was already pressed against mine. I imagined the leg was saying, I am a man and you are a woman and we’re stuck with this artificial intimacy, so let’s go with it.

Burt ordered a club sandwich, anointing it with ketchup, and sweetly tolerated a dozen interruptions from passing fans.

“Don’t you just want them to go away?” I asked.

He shrugged. “I sat there for fifteen years while people reached across me to get someone else’s autograph, asking me, ‘Are you somebody, too?’ ”

The heat was oppressive the next morning, the mosquitoes bigger than chickens. Burt, as moonshine-runner Gator McKlusky, would tangle with a gang of toughs, the cops, and the sheriff in the dusty rubble. Burt would be shoved, pummeled, fly through the air, and wind up hanging in the crook of a tree.

“Everybody thinks I’m an ass for doing my own stunts,” he told me. “Number one is that I like doing it. And in the long run, I’ll be a better McKlusky.” Between each take, someone handed Burt a glass of vodka spiked with Gatorade.

Just as the camera was lugged into place, the sun disappeared. Burt lounged during the break, admiring his co-star’s legs. “Cyd Charisse’s are even better,” he volunteered. “And for the best keester in Hollywood, it’s Vera-Ellen and Mitzi Gaynor. As for boobs …” He pondered, watching me take notes. “There’s a problem. Big boobs are wonderful, but after six hours you get tired of them. Small little boobs, they just sit there and stare at you. They’re wonderful, too.” I couldn’t decide if he thought he was amusing me or just playing Burt Reynolds. It was his Johnny Carson persona.

We moved into the star’s dressing room—not the giant luxury trailer I would have expected, but, rather, a cramped tin can on wheels, left over from a low-budget shoot. Burt propped his feet on a rusty metal locker after blending an alchemy from its contents—frosty vodka, limes, near-frozen tonic nestled in a bank of ice.

The sun broke out again. The crew scattered peat moss over brush and scraggle to soften the falls. Burt unzipped his dungarees and started stuffing padding around his flanks. I couldn’t help but notice—I guessed I was expected to notice—that the Cosmo centerfold did not do him full justice. Oh dear. I had to pull myself back to reality, remembering that I had vowed not to be a pushover.

So why did I suggest that we have dinner in his apartment atop the hotel that evening? To escape the dining room’s constant intrusions, of course. Burt looked relaxed. We stood on the terrace, watching lightning cut fissures into an elephant-gray sky, when the buzzer sounded. Oh. Yes … a female wanting photo and autograph. Then another.

“Do you think we could pretend there’s no one out there?” I asked.He agreed we could ignore the buzzer.

“Want to see the horse I bought today?” He handed me a photo of a spindly freckled colt. “I bought him by telephone.” Burt called room service. Two vodkas and tonic for Burt. Two glasses of white wine for me. “That’s what money is for,” he confided.

“Room service. Horses. Flying your friends in to visit the set.” Money had bought the 180 acres of Florida ranch, the house built by Al Capone, where his parents lived, the land in Tennessee, the California house and its gate with the giant fretwork R.

This time, the knock announced room service. The waiter wheeled in a table covered with a white cloth. Burt lighted candles.

“I called Clint Eastwood to check you out,” he told me, leaning back on the sofa, sipping his vodka.

“I guess he said I was okay.”

All the time I was listening, taping, sipping my wine, and analyzing the man, I was trying to remember why it had seemed so important to stay vertical. Suddenly, instead of a smart-ass cocksman, I was imagining some element of insecurity in this hypersexuality. Oh no. Vulnerability.

My weakness. His conversation was sexier than the actual seduction moves of most men. And I let him talk, let him alternate between superstud and sensitive Mr. Wonderful.“I’m getting talked out,” he warned. “I told my agent I can’t do any more of these interviews. I don’t want to talk about anything for three months. I’ve just been so f—— honest.”

I was talked out, too. To hell with denial, I thought. If my life depended on it, I couldn’t remember why it was I was not going to make love to this adorable man. I moved toward him and offered my mouth.

He let me kiss him. Oh, what a wonderful surprise. He really knew how to kiss—and everything else.

5. GILBERTMaguy Le Coze was a saucy, flirtatious sylph in a futuristic jumpsuit, with a shiny Dutch bob and thick black bangs drifting into dark-kohled eyes above a turned-up nose, and Cupid’s-bow lips so red and perfect, they might have been painted on with enamel. This was the first time I saw her, fussing playfully over the Parisian regulars who’d brought me to the original little cubby Le Bernardin on the Left Bank in the spring of 1977, a few years after its launch. So she might have been just 32, and Gilbert, the handsome swashbuckler in blue jeans and a fishmonger’s apron, too shy to come out of the kitchen at first, was just 31. He had a thick shock of shiny brown hair, significant sideburns, and a mustache below his straight pointed nose, which he would twitch like a truffle dog in the heat of the hunt. For me, it was instant infatuation. I had a crush on them both, and on the stunning simplicity of the seafood, as well. Tiny gray shrimp nesting in a crock, delicate and sweet. Saint Pierre set raw on a plate, then bathed in a coriander-spiked broth before reaching the table opaque and sublime. For me, it was a delicious package, a find for New York readers—this adorable brother-and-sister act in an out-of-the-way spot on the quai, and Gilbert’s brilliantly minimalist fricassée de coquillage, the barely cooked salmon with truffles, and his riff on raw fish lightly slicked with olive oil. Because Gilbert was untutored, he had no choice but simplicity, Maguy has written. The idea of raw fish, she says, came from Uncle Corentin, at sea off Brittany, who would take a fresh-caught cod, skin it, and eat it on bread.

Maguy and Gilbert had moved in 1981 to a bigger space on rue Troyon by the time I returned. Gilbert was infinitely less shy and cooking more confidently than ever. Now at dinner in the Brittany sky-blue nook off the Champs-Elysées, I was that writer who had followed the Le Coze star for New York’s impressionable readers, the properly smitten Pied Piper whose lyrical waxings had prompted a flow of impressionable mouths from America. Small saucers of new dishes I must taste punctuated the meal. Gilbert urged me to join him after the kitchen closed that night at Castel, the late-night hangout for chefs and food-world habitués, Gilbert’s usual haunt, where he smoked relentlessly and downed cognac after cognac. And we danced—disco but tight—rubbing into each other, provocative vertical seduction. Suddenly, we were in a taxi, kissing, caressing, zipping, unzipping. I hugged myself together to get through the lobby of my hotel.

Inside my room, I had time only to drop my handbag on a chair. “I need to sleep a little,” he said afterward, in French. He had me set my alarm for 4 a.m. I was deep in sleep when he woke us. He pulled me close and kissed me, and just when it seemed like we might be leaping off a cliff again, he jumped out of bed. “I can’t be late for the market,” he said.In 1986, when they opened Le Bernardin in New York, I went that first week. Already, it was wonderful, very French, very proper, the waiters drilled daily, to the point where many were protesting the extra hour required for the daily training session. The lazier ones left. The survivors got their rough edges sanded. Halibut (at two dollars a pound), never before seen on an upscale menu, was suddenly an aristocrat—the Eliza Doolittle of the sea. And more sophisticated New Yorkers—already disciples of the sushi faith—were primed to ooh and aah over raw black sea-bass slivers with cracked coriander seed and thin ribbons of salmon “cooked” in an essence of tomato scented with olive oil, cracked coriander, and grains of cumin. So simple, so lush, so seductive. How wonderful to have a mouth. What a time to be a restaurant critic.

I wrote a rave. The Times followed with highly un-Timesian speed, dropping a four-star benediction. Gilbert was already on to a new life, rich with caboodles of blondes and restless wives slipping him phone numbers, drinking late and dancing at Au Bar. He didn’t speak much English, but he didn’t have to.

He was just 48 when he died, in 1994. It was impossible to believe that he could fall asleep in the gym and never wake. He was not just a lover and my friend; he was the great god of fish. Everywhere, American menus acknowledge the fish he discovered and his minimal hand with raw slivers and fillets. Chefs who had never met Gilbert came to say farewell. It seemed especially cruel that a man who had so fiercely embraced life could simply stop breathing. “I’m not a domesticated animal,” he used to say to his chef de cuisine, Eric Ripert. “I’m a wild animal. I want to be a panther.”

With the art and soul and passion of Ripert, Le Bernardin is astonishingly more wonderful than ever. Except that Gilbert is not in the kitchen or flirting at the bar in his whites. I am never there without feeling his presence. I remember always stopping to watch the amazing ballet of dinner service, throwing a kiss to Gilbert through the window that is no longer there. I wonder if he is furious for the cruelty of dying so young.

Gael Greene Audio Clips

- On Sex With Elvis

- On the Call to Be a Critic

From the book: Insatiable: Tales From a Life of Delicious Excess, by Gael Greene.

Copyright (c) 2006 by Gael Greene. Reprinted by permission of Warner Books, Inc., New York, N.Y. All rights reserved.