John Updike was afraid of ghosts until he was 65.

“Why 65?” I ask in astonishment—why not 35, 55?

“Well, I don’t know, I just outgrew it suddenly! I’d been in enough houses and been through enough nights that I felt for sure the odds were that there were no evil spirits out against me.”

I feel a twinge of guilt; I might be such a spirit. The Widows of Eastwick, Updike’s latest book, the sequel to his 1984 best seller The Witches of Eastwick, has left me cold. The original was such a dazzling jolt of black comedy, so pure in its malice and pointed in its satire, that the news of a follow-up seemed to promise a great deal; and yet this new book felt stuck, slack.

In tan trousers, perched on his hotel suite’s elegant sofa, Updike, 76, is at once gracious and blunt in response to my couched criticisms. He describes his decision to revisit his old hit as “more crass than it ought to be.” None of his books were intended to have sequels, he points out: not Rabbit, Run and not the wonderfully funny Bech: A Book, each of which led to a series of successful sequels. And when he reread The Witches of Eastwick, he felt pleasantly surprised at its energy and inventiveness, finding “the author was really at home with this material and felt keenly about it.” That ghostly fictional world, those three vivid characters, seemed “live enough to think it would be good for one more ride.”

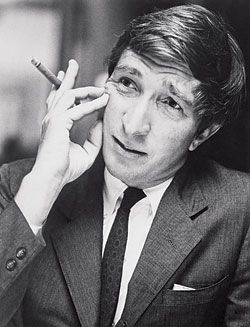

Updike has spent much of his long career perfecting a certain breed of anti-hero: the hyperobservant, resentful, libidinous fifties-era male who uses sex as a ballast against his diminishing status. It’s a theme he shares with Philip Roth and Norman Mailer (not to mention Woody Allen and Hugh Hefner), and yet Updike’s elegant prose set him apart. For many decades, he was the American bard of infidelity, a Puritan dirty-book writer whose beaky handsomeness was everywhere—the Wasp schnoz; the thatch of white hair; the curious, amused features. His worlds were stained with Christian guilt, his tone lyrical rather than pugilistic. On the cover of Time in 1968 for Couples, he hovered in that heavenly spot between literary genius and mass-market phenomenon, an avatar for the national struggle to reconcile stability and freedom.

The Witches of Eastwick marked Updike’s first attempt to delve deeply into female psychology. Like his peers, Updike had been taken to task for sexism. But unlike them, he “rose to the bait” over the years, he tells me with a certain satirical opacity. “People of my age are raised to be, sort of, chauvinists. To expect women to do the laundry and—it’s terrible! I’m making you cry, almost! But I’m eager to correct that as a writer, more than as a person. As a person, we always have chauvinistic assumptions. But a writer is supposed to be open to the world, and wise, and generous.”

Witches was not Updike’s only experiment with writing from a woman’s perspective; he’s done so in books including S. and Seek My Face. These experiments were not unpleasant. “To a misogynist,” he notes drily, “it’s bliss to write from a woman’s point of view.”

Yet The Witches remains the most successful of these gambits, a poignant, nasty, hilarious, filthy parable—written in the eighties and set in the late sixties—about the dangers of free women. “The era in which I wrote it was full of feminism and talk about how women should be in charge of the world,” recalls Updike, waggling the antennae of his eyebrows. “There would be no war. There would be nothing unpleasant, in fact, if women were in charge of the world. So I tried to write this book about women who, in achieving freedom of a sort, acquired power, the power that witches would have if there were witches. And they use it to kill another witch. So they behave no better with their power than men do. That was my chauvinistic thought.”

In essence, in his attempt to pay heed to his feminist critics, Updike bridled instead, producing a different type of achievement: a genuinely great misogynist novel, an explosive mix of empathy and malice. The witches in question are Alexandra, Jane, and Sukie, a coven of divorced mothers in a small New England town. The trio sleep with married men; they neglect their children and drift into orgies with the devil—who arrives in the form of a pushy New Yorker, Darryl van Horne, with a taste for Pop Art and a hot-tub-equipped mansion. But they also possess a real charisma, an anti-heroic force, their spells a springy metaphor for sex, for art, for freedom, for all the possibilities of the self detached from devotion to others.

At one point, the book even makes a coy meta-argument for its own genre, in a reference to one of Van Horne’s prized art pieces: a female figure, legs splayed, made of chicken wire and flattened beer cans, with a porcelain chamber pot for her belly. Alexandra, a sculptress herself, complains that the Ed Kienholz statue is “rude, a joke against women,” but the devil argues for its genius. “The tactility! There’s nothing monotonous or preordained about it … The richness, the Vielfaltigkeit, the you know, ambiguity.” Reluctantly, Alexandra’s hand creeps out to find “the glossy yet resistant texture of life.”

Even after 24 years, The Witches holds that same unsettling texture: Its protagonists are well-developed characters who are also damning cartoons. In the end, the women prove vulnerable to the devil’s blandishments (he plays to their vanity by bloviating about his love of women) and sink into jealous cruelty—then brew up the new husbands one suspects they wanted all along. Yet a peculiar sympathy undergirds the book’s coldest instincts.

In The Widows, Updike’s awed malice seems to have curdled into something like contempt. Bereaved, the witches—who have drifted apart—reunite to travel. They grieve, they get on each other’s nerves; finally, they return to Eastwick, where they make modest attempts to repair their social crimes. Their artistry, a major element of the original book, has dwindled to a nub: Alexandra spins a pot or two, Jane has abandoned her passionate cello playing, and Sukie writes gloppy romances, the hack effusions of a silly woman.

“What can I say about that?” Updike shrugs. “With the waning of everything, with the waning of the sexual drive, the witch capacity, there probably goes a certain lessening of artistic passion. I suppose I feel that in my own work. The world would really be none the worse if I were not to write anymore. But I keep wanting to do it, in part to fill the time. I don’t know what you’ve found, but nothing makes the time pass so much as writing. You look up, and two hours have gone by!” He smiles suddenly. “You know? It’s a wonderful antidote to boredom or dullness.”

It’s an astonishing thing to hear from an artist whose early years were a model of aesthetic ambition. Growing up in the small working-class town of Shillington, Penn., Updike went to Harvard on scholarship, then swiftly achieved his own grandest literary dreams. He moved to New York, made his name at The New Yorker, and had a wife and child at 22. (He has fond memories of their railroad apartment on 13th Street—so small they were forced to move the crib from room to room in order to sleep.)

“The world would really be none the worse if I were not to write anymore.”

When a second child came along, the couple moved to the suburbs, and Updike found he was relieved to be free of other writers. “I wanted to be the only lion in that part of the Serengeti,” he tells me. In the decades since that migration, Updike (unlike the blocked Bech) has been famously, almost supernaturally prolific, publishing 23 novels and more than a dozen short-story collections as well as reams of memoir and criticism. Along the way, he’s shown a capacity for stylistic risk—a quality that has guaranteed, and perhaps lends Updike the right to, a set of serious duds among his masterpieces.

In Updike’s view, part of the value of revisiting the witches was the opportunity to write about aging and death. “Taking those women into old age would be a way of writing about old age, my old age.” In this spirit, he took his witches on the same travels he has made, to Egypt and China, and he lent them some of his own sense of vulnerability, “the physical oddities I notice in myself, the arthritic pains, the perennially imperfect teeth. I’ve been spared baldness, but in a strong hotel light, you suddenly see your awful head that you never had to look at before.”

And yet whereas Updike has continued to publish, his witches have lost their art. I tell him I’m disturbed by this, by the way the book seems to conclude that motherhood is all. The first book, for all its satire, was set in a universe in which women’s possibilities seemed radical, infinite, in which, no longer defined solely by their families, they could do anything—smash a thunderstorm into a beach full of dismissive teenage boys, say. In the sequel, such ambiguity is snuffed. No longer fertile, or desirable to men, the widows are nothing.

Updike argues that his take is historically accurate: Witches were considered “the enemies of children.” Parenthood is existentially different for women—more demanding, harder to balance with work—while men are considered good fathers merely for winning bread. In his own family, Updike found being an artist an advantage. “You’ll have to ask my children, but my image of myself is as a casual but loving father who could bring to my four children the virtue, let’s assume it was, the virtue of my being more present than the fathers who were commuting all around us.”

It was only after he divorced his first wife that he had to “modify my opinion about myself as a father.” A good father “wouldn’t have gotten the divorce. The divorce was very much traumatic for all of us, and especially for me, since I was the one who wanted it.”

It occurs to me that divorce is as much a central subject of The Witches as female psychology. It is Updike’s original sin. “I was in control!” he recalls of his own divorce, in 1977, when he left his first wife for his second, to whom he has been married for 30 years and with whom he shares several stepchildren. “I’ve tried to be a bystander for much of my life. But I couldn’t pretend to be one in this instance, and so I felt guilty for years. My stammer came back when I would talk to my own children. But time has gone, and that was 30-odd years ago, and they’re all adult and seem cheerful. And they live close, so I’m able to observe somewhat.”

He and his first wife went to therapy long ago, back in the sixties, he says. “It was done. A little like adultery: It was done. I was unhappy and restive; my doctor thought it would be good for me. I was conflicted, too—you may say these are descriptions of the human condition. There were certain unexamined, perhaps, looking back on it, unexamined aspects of my sense of myself. Even though as a writer you’re spilling your guts all the time, aren’t you? You’re dealing with somewhat the same deal the psychiatrist tries to get you to look at.

“It was good. It was sort of empowering too.” But he sounds doubtful even as he says this, uncertain perhaps—this notion of health seems so corny, an end to everything, to guilt itself, that enduring life force that has fueled so many of his works. “They make you feel sort of good to be you.”