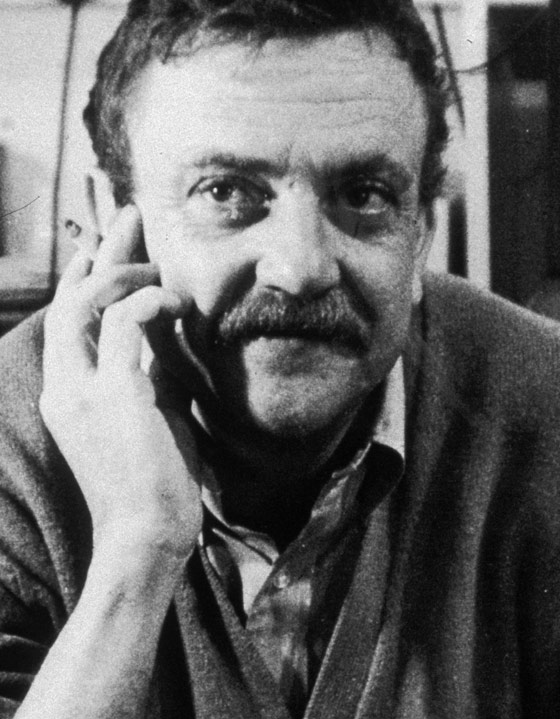

A cranky ostrich in a rumpled suit, Kurt Vonnegut might seem an odd fit for the staid Library of America. (His advice to young writers? “Literature should not disappear up its own asshole, so to speak.”) But Vonnegut, like his hero Mark Twain, has always been something of a paradox—a beloved grouch, a man who has a bad thing to say about almost everybody but for whom no one has a cross word.

Scratch many a satirist and you find a wounded optimist still hoping to chip away at the world with the pick of his derision. In Vonnegut, though, one rarely senses the reformer’s zeal that energizes so much satire, from Swift to South Park. Doom, in his novels, is a given. The foreshadowing is all but lacquered on, so that early in Cat’s Cradle the end of the world is guaranteed. In Slaughterhouse-Five, characters’ fates are often meted out the moment we meet them. “There are almost no characters in this story,” Vonnegut writes in the novel, “and almost no dramatic confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the listless playthings of enormous forces.”

Slaughterhouse was an unlikely book—an earnest war novel tricked out with pomo special effects and framed with a loopy sci-fi conceit. And it transformed Vonnegut, a genre-fiction workhorse and WWII vet, into an even unlikelier hero of the counterculture. Almost instantly, the novel joined Catch-22 (1961) and V (1963) in the rabidly dog-eared, passed-from-friend-to-friend canon of literary cult objects. Like “Catch-22,” its immortal refrain “so it goes” seeped into the national parlance, even rising to the level of protest mantra. (To appreciate how weird this is, compare it with “Yes, we can.”) Today, his influence is so ubiquitous as to be invisible, though carbon traces can be detected in the work of any writer who deploys earnestness under cover of irony. And as far as I can tell, Vonnegut remains one of the very few socially mandatory reading experiences of high school.

If Vonnegut speaks to the eternal adolescent mind, it’s because he so ably inhabits its favorite moods: hellacious pessimism and utopian love. How he balances the two—if he balances them, really—is an open question, and part of the wonder. His work relates fundamental horror in a tone that’s zesty, warm, and somehow consoling. One finishes a Vonnegut book weirdly buoyed by the prospect of apocalypse. And there is plenty of apocalypse: Cat’s Cradle leads us to the end of the world, and Slaughterhouse orbits the horrific Dresden bombing, which Vonnegut witnessed as a 22-year-old POW and about which, he wrote his parents from Le Havre, he had “damned much to say.”

Vonnegut sent that letter in 1945; he didn’t publish Slaughterhouse until 1969, 25 damned years later. “I would hate to tell you what this lousy little book cost me in money and anxiety and time,” he writes at the beginning of the novel. When Vonnegut tells the movie producer Harrison Starr that he’s planning a book about Dresden, he writes in the novel, Harrison quips, “ ‘Why don’t you write an anti-glacier book instead?’ What he meant, of course, was that there would always be wars, that they were as easy to stop as glaciers. I believe that, too.” Vonnegut states the problem differently in the preface to a later edition of Slaughterhouse, included in this Library of America volume: “Atrocities celebrate meaninglessness.”

At first glance, the novel might seem to celebrate meaninglessness too. Kidnapped by aliens, Billy Pilgrim, the protagonist and clear double for Vonnegut, trips through time, waking up at different points in his life: his honeymoon in Cape Cod, a fetid German boxcar packed with POWs, a zoo in a foreign solar system. Eventually, he is led to a distant planet called Tralfamadore, where he learns that humans perceive time erroneously, that all events happen simultaneously. As Billy tries to explain to his fellow humans, “The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at the funeral.”

Vonnegut’s fiction often quakes with ambivalence about the efficacy of writing, but here, in sci-fi, he finds an improbable moral purpose. The conceit of time travel simulates the cosmic disorientation of a POW, yes. But it also allows us to behold man in all his tininess and futility—and not just to “put things in perspective” but to celebrate our capacity for a galactic bird’s-eye view. We cannot write our way out of catastrophe, so go the implicit metaphysics of Slaughterhouse, but we can imagine a universe in which odd green creatures observe each death from millions of light-years away and, in observing, honor it. Vonnegut is less a satirist than a morally serious escapist: He spins a yarn that makes the ant farm of Earth more tolerable.

In Cat’s Cradle, the religious guru Bokonon manufactures harmless untruths called “foma.” The concept is not a knock on the opiate of religion, as one might first suspect, but a metaphor for the essential uses of fiction. The book’s epigraph is telling and ultimately sincere: “Nothing in this book is true. Live by the foma that make you brave and kind and healthy and happy.” Or, as the heroic Eliot Rosewater puts it, “I think you guys are going to have to come up with a lot of wonderful new lies, or people just aren’t going to want to go on living.”

To call a novel like Slaughterhouse-Five a happy lie is not to denigrate the book but to elevate the art of falsehood. After all, it’s base and easy to sell people shitty lies. Charlatans, politicians, and conformists do it every day, and Vonnegut was as pitiless as Twain in exposing them. It’s a much harder task to give them wonderful ones, doubly hard in the face of tragedy. As Vonnegut himself said, the arts are “a very human way of making life bearable.” By that measure, what is more humane than telling people they’ll be all right, especially when they won’t be? And what more generous gift than to convince them?

Kurt Vonnegut: Novels & Stories, 1963–1973

Library of America, $35