A year ago today, I lived in the hospital. I had a 1-year-old daughter with a blood cancer that ordinarily kills three-quarters of the persons it afflicts. The same illness, acute myeloid leukemia, had recently felled the idol of my youth, Susan Sontag. Here was a woman who had beaten back two previous cancers and who, according to her son David Rieff’s 2008 memoir, Swimming in a Sea of Death, commanded the best doctors fame and fortune could attract—as well as a positively Rabelaisian will to live.

Every day of the seven months that I woke next to beeping IV poles and blinking heart monitors as Eurydice (she has a Greek name to honor her half-Greek pedigree) underwent powerful in-patient chemotherapy, I thought hard about death. I’d spent the previous part of my life thinking, and writing, about love. Sex and death, Yeats once wrote, are the only subjects worthy of a poet to address. If that were true, I thought as I writhed in discomfort on the plank-size pull-out chair that was my bed in Eurydice’s isolation room, I was taking them up consecutively. Not that I had time to write in this period, or read. An effervescent infant with highly disrupted sleep patterns who can’t move without yanking the tubes out of her chest will keep even the most industrious scholar from her books. But I recalled what I’d read in earlier incarnations—the poems of Shakespeare, of Sidney, of Donne, of Keats. Death in these verses was not merely a source of fear but of beauty. Their authors serenaded it as they serenaded the women who’d stolen their hearts—often in the same pair of lines: Keats, for example, will tell his betrothed he wished “still, still to hear her tender-taken breath / And so live ever—or else swoon to death.” In Shakespeare’s sonnets, the speaker insists repeatedly that he will soon die: “This thou perceivest,” he informs his paramour, “which makes thy love more strong / to love that well that thou must leave ere long.”

It is hard to deny that these guys were onto something. If we attend as intensely as we do to last words and deathbed pronouncements, it is, at least in part, because we treasure the very moments that seem to us most fleeting. Far from being a source only of darkness, transience is a source of light. “I wish,” writes Rieff in his memoir of Sontag, “that I had lived, while [my mother] was alive and well, with the image of her death at the forefront of my consciousness.” If we could only surround ourselves by skulls and wear lockets around our necks with the death dates of our dear ones inscribed, we might just be better people. But we do the opposite. In contemporary American culture, death is all but invisible. It is undiscussed, glossed over, hidden away, disappeared. In a society in which almost every adult has pored over thousands of images of copulating bodies, most of us have never laid eyes on a dead one. Even in the hospital—where the dead are ubiquitous—they are almost impossible to witness, or indeed acknowledge. Hospital staff are trained to omit all mention to outsiders of the existence of death. They are trained to be silent about what is going on in the next room.

In The Long Goodbye, the newest book of a recent wave of memoirs about the end of life, Meghan O’Rourke argues pertinently that death is our last, or at least greatest, taboo. Before it occurs we are encouraged to deny it, and after it’s occurred we are enjoined to put it behind us as quickly as possible: “An enduring psychiatric idea,” writes O’Rourke in her meditation on her 55-year-old mother’s death from cancer, “is that the mourner needs to ‘let go’ in order to ‘move on,’ and in the weeks after my mother died, people kept suggesting as much.” O’Rourke doesn’t think much of the notion: “I didn’t want to let go,” she states defiantly. “And in fact studies have shown that some mourners hold onto a relationship with the deceased with no notable ill effects.”

There is disagreement on that front among recent end-of-life memoirists: In A Widow’s Story, Joyce Carol Oates documents her own effort to stride forward. Oates spends exactly 35 minutes (by her count) with her husband of nearly 50 years after he dies alone following a seven-day battle with pneumonia. Having arrived in his hospital room at 1:08 a.m., she’s gathered his possessions, called her friends, and pronounced final farewells by 1:43, at which point she’s outside again, inquiring with the astonished night staff about funeral homes. “You have time,” says the nurse. That’s not how Oates feels. “There will never be a right time … to turn my back and walk away,” she observes—so she turns her back immediately. It’s no shock that thirteen months later, she has remarried—a fact she fails to mention in her 415-page memoir.

We each face—or fight—death in different ways. But I’m with O’Rourke when it comes to “outing” death, lingering with it, feeling it, and failing to minimize its violence. I’m with her when she bristles at the facile way people say that “at least my mother [is] ‘no longer suffering’ ”—as though illnesses were never cured, nor accidents averted. I salute her when she rails against “a world where there were so few rituals to guide me through this loss.” I endorse her call for ceremony, discussion, indignation—her resistance to that false idol of modernity called closure. For what is closure but another way of telling the departed “I’m through with you”? The package is sealed, shelved, and forgotten. We owe our dead, and ourselves, better than that.

“To philosophize is nothing else but to prepare for death,” wrote the great sixteenth-century French essayist Montaigne, echoing Cicero and Seneca. To be intrigued by life, he insisted, is to be intrigued by death. It is only in our own day that intellectuals so often shirk the subject of mortality, irresponsibly abandoning it to clumsy clinicians and raging religious fanatics. The emergence, at this moment in history, of a small but significant cadre of end-of-life thinkers signals a sea change, a return to essentials, a cause for hope.

For death is not merely a scourge and scoundrel; he’s a teacher. For centuries he has taught poets and peasants alike to “seize the day,” as the phrase goes: to live more intently and intensely and to love more gratefully, generously, vocally, and urgently. Death teaches us to write love letters to absent parents, like O’Rourke—or to absent daughters and husbands, like Joan Didion, whose surprising work, The Year of Magical Thinking (2005), inaugurated this current movement of end-of-life memoirs. If we’re lucky, death even teaches us to write love poetry while those we cherish are still at our sides.

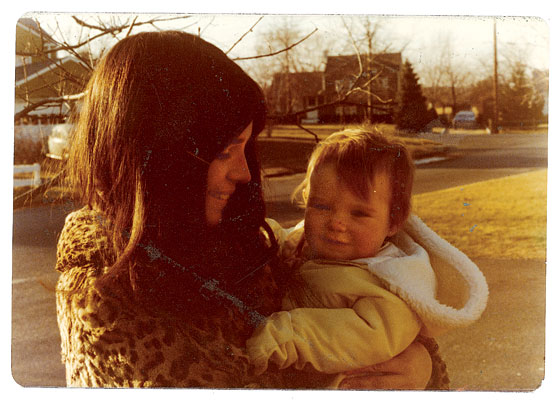

This is what happened to me. As I set down these words, Eurydice is a leukemia survivor. The bulky chest catheters that sat under her skin like oversize ice boxes under a silk scarf have been surgically removed, the chemo drip arrested. To the eyes of machines, there is no more cancer in her blood or bones. She is an apple-cheeked, beaming girl. I stop her carriage halfway through the crosswalk and cover her face with kisses.

And yet, I’m not sure how good a mother I’d have made if we’d enjoyed easier fortunes from the start. I was a reluctant convert to parenting. The pregnancy that led to Eurydice’s birth was unplanned. But from the moment she appeared—and grappled, instantly, with medical problems that progressed toward acute leukemia—I was her champion, her cheerleader, her love-struck knight. When I realized she might truly die, and that nobody around us, in fact, grasped what death meant—not the surgeons nor the social workers nor the oncologists who appeared at her crib side—I thought strongly about accompanying her. Wherever it was she was going, whatever state of unconsciousness or consciousness she was headed for, I did not want her to go alone. I did not want to push my little girl ahead of me, like a guinea pig or a hostage, into a realm nobody knew.

In our death-prude society, this seems like a harebrained way to think—almost certainly pathological—but in other traditions and instances, it appears quite lucid. The husband of the early-twentieth-century poet Edna St. Vincent Millay proposed to die with his first wife, and when Millay was ill, followed her deep into morphine addiction in order to understand what she was suffering. Kleist ended his days with a girl he loved who was mortally ill. I am glad I never had to make this call, but grateful at the same time that I had occasion to consider it. Life and love seem deeper, sweeter, and clearer for it.

The omnipresence of death is not to be feared but to be mined. After all, as Seneca reminds us, it may be as silly to tremble that we will one day cease to exist as to grieve that we did not exist before birth. Like O’Rourke and her fellow memoirists, we all crave eternal life for our loved ones and for ourselves. And yet life at any length can be rich, as I saw, in spite of myself, during those months in the hospital with Eurydice. In the middle of chemotherapy, my 1-year-old blew exuberant kisses and laughed too loud: Nurses used to visit our isolation room after hours for their “Eurydice fix.” Had she not outlived her leukemia, as the 25-year-old Keats did not outlive his tuberculosis, it would have been an outrage—but it would have been hard to find many octogenarians who’d packed more joy into their years. Every object—and every life—is beautified by an awareness of boundaries. It is not because a haiku is shorter than a novel that it is inferior. Mortality is no butcher. He may, in fact, be an artist.

The Long Goodbye

By Meghan O’Rourke.

Riverhead. $25.95

A Widow’s Story

By Joyce Carol Oates.

Ecco. $27.99

Swimming in a Sea of Death

By David Rieff.

Simon & Schuster. $14