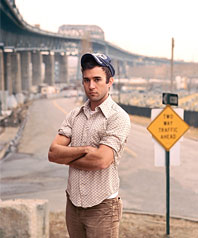

Sufjan Stevens may be the first 32-year-old indie darling to have his classical debut at the Next Wave Festival, but he’s in no danger of becoming Leopold Stokowski anytime soon. He stands in a rehearsal room at BAM with the gelatinous bearing of someone who’s taking a big risk and just might fall on his face in public. He hugs his thin arms to his chest and tucks his hands into his armpits, drops them nervously to the sheaf of notational papers on his music stand, then scratches his chin. He’s bedecked in cool-Brooklyn finery: a black T-shirt with a faded map of the United States on it, black cargo pants, sneakers, and not one but two hats—a baseball cap topped by a wintery thing with Sherpa earflaps curling into space.

“Let’s do B onward,” he says, referring by letter to a section of his 30-minute, seven-movement orchestral suite, The BQE. His musicians—three or four each of brass, woodwinds, and strings—don’t pay much attention. They’re a young, not-at-all-staid bunch, bantering avidly among themselves about their parts. Scattered among them are empty chairs for the players who couldn’t make it to rehearsal. Stevens’s conductor isn’t here today, either. “I’m terrified to conduct,” he mumbles. “I can do some tapping.” He refers to his pages again, then briskly announces, “Let’s start at C … C, yeah.” He holds a pen in the air and prepares to count them down. “Let’s do this on five!” An involuntary gasp escapes him. “Oh boy,” he whispers.

The musicians raise their instruments, and on five, they strike up. Trumpet, trombone, and French horn stomp an angry rhythm. Flute, clarinet, and oboe begin trilling wildly over them. The string section saws and screeches. The sound is frenetic and chaotic, but for a minute or so it holds together, a clashing cacophony of busy traffic and super-speeded city life. It’s almost like cartoon music, with heavy, doofus-y bass parts and shrill, high titters. Then, without warning, the brass section gets ahead of itself and the rhythm starts to come apart. The woodwind trilling turns into a hissy argument. Instruments cut each other off, change lanes without warning, and crash into one another. It’s a multicar pileup!

Stevens waves his pen in the air and can’t help smiling. “I’m sorry,” he says as the sound dies down. “That was awful.”

It’s not easy being 2007’s wacko cultural wonder boy. For three nights beginning November 1, Stevens—cult-embraced purveyor of freaky chamber folk-pop—will present an actual symphonic evocation of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. The challenges here are many-layered. Though Stevens has arranged orchestral bits for his records and taken string sections on tour, he’s never attempted anything of this complexity: writing and rehearsing a purely instrumental piece for 38 musicians that also happens to have a visual component (16-mm. film shot by the highway). And the musical parts themselves are complex—it’s not like the players are blowing an eighth note here and there. “The parts are challenging,” says French-horn player Theodore Primis. “You look at the page, it’s just black notes. Tons of black notes.”

“It’s definitely very busy,” Stevens agrees. “The piece is about constant motion and repetition. A lot of it is written in canon form, so there are repetitive sequences of chords and melodies that start to overlap and form a round. There are fugue elements as well. It introduces themes and then deconstructs them later on.”

The fact that he’s new at this clearly has Stevens daunted. “It’s definitely beyond me. I’ve started to develop an interest in music that is far removed from my abilities. And that’s very frightening, because a lot of the life of the music is out of my hands, and I’m incapable of performing or playing most of it. So I have to hire these professional players to read it for me.”

What’s more, this is a piece about one of the ugliest roadways known to New Yorkers, a road every outer-borough navigator hates with an instinctive passion. Think about the BQE, and you think of decaying tenements, boarded-up warehouses, grime-encrusted retaining walls, and pothole-pocked pavement. You think of smog, congestion, and poor urban planning. You think, Get me out of here! What you probably don’t think is, Wow, this would make a great symphony!

Yet Stevens, who lives in Brooklyn, says the decay was part of the allure. “The movements each have a way of evoking images, sounds, and sensory information based on experiences on and around the BQE. But it’s taking those sensory experiences—which in reality are very mundane and urban and sort of uncomfortable—and romanticizing them, exaggerating them in some ways, so that they become more sublime and beautiful. It’s a beautification of an ugly urban monument.”

Sufjan (pronounced SOOF-yan) Stevens is, on some level, the perfect person for this weird task. His albums have shown him to be a master of intricate artifice; he builds little sonic shadow boxes, filling them with odd, unconnected details, frequently playing most of the instruments himself—hermetically sealing his hushed, vaguely tormented voice at the center. He’s also demonstrated a flair for high concept. His 2001 album, Enjoy Your Rabbit, released on his own Asthmatic Kitty label, offers paeans to the different signs of the Chinese zodiac. And in 2003, he began what he claimed would be a 50-album suite about the states of the union. Greetings From Michigan: The Great Lake State eulogized failing towns with banjo, piano, and irregular time signatures. Come On Feel the Illinoise was grander and artier, with ridiculously cumbersome song titles like “To the Workers of the Rock River Valley Region, I Have an Idea Concerning Your Predicament, and It Involves an Inner Tube, Bath Mats, and 21 Able-Bodied Men” balanced out by a couple of genuinely rockish tunes that ended up on TV soundtracks.

Illinoise was a big deal in the small indie pond. It made critics’ top-ten lists and won Stevens a New Pantheon Award, which goes to albums selling under 500,000 copies. Mainstream success came calling. Stevens ignored the overture. “I’m getting tired of my voice,” he complained to the music Website Pitchforkmedia.com, which worshipped him. “I think the direction I’m going to go next is to work with a small string-and-horn ensemble and do more composition and arrangement.”

Then he received a proposition to do just that. Joseph Melillo, executive producer of BAM and the first producer of the Next Wave Festival, happened upon Stevens’s 2006 “American Songbook” concert at Lincoln Center. “I have a Geiger counter for originality,” Melillo says. “It hit me fast in the face: This is original. This is off-center. There’s subtext here. It was beautifully interpreted, well-crafted music.” Melillo immediately began plotting ways to book Stevens himself. “I got in touch with him, and I said, ‘You should have a relationship with this institution. [It’s] here to service you as an artist. I want you to have these resources available to you.’ He said yes, and I said, ‘Okay, I’m now going to commission you.’ He didn’t know what that meant, so I had to go through the definition of what the verb to commission means.”

Melillo doesn’t think there’s anything cynical about using Stevens to bring kids into his academy. “Philip Glass is 70 years old,” he says. “Steve Reich is 71 years old. Laurie Anderson is 60. Those are the facts. I’m trying to pass the baton to another generation, who should have the same opportunities that this senior generation had 20, 30 years ago.”

But Stevens sees his classical sojourn as an exercise, not a long-term career goal. “I have a suspicion against new-music personalities,” he says. “There’s a certain kind of pretension. And I cannot pretend to be part of that environment, because I don’t have the experience, the skills, or the abilities. My music—even this kind of chamber music—is still very much based on pop idioms. It’s not based on new-music theory. But I enjoy pretending to be a composer. I’m sort of a hack at it. It’s fun to indulge in that.”

For all his free-flowing self-deprecation, Stevens loves talking about work. He’s big on research—the BQE project sent him scurrying for info about its architect, Robert Moses. “The Robert Caro biography is extremely thorough and extremely interesting, but there’s very little about the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway,” he says. “The Cross Bronx Expressway was the bigger story. That was the poster child for Moses’s bad urban-planning schemes. There isn’t as much scholarship around the BQE, which may be why it interested me.”

Shift to more personal lines of inquiry, though, and Stevens gets all fidgety. He grew up in Michigan? “Yeah.” Brothers and sisters? “Mm-hmm.” How many? “Two brothers and three sisters.” Stevens likes to say that his childhood has little bearing on his work. “My upbringing was very mundane,” he says. “It was about making ends meet and putting food on the table and doing the chores.” What did his parents do? Blank look. “What did they do?” he repeats. Vocationally, I say. “They had different jobs,” he responds, with growing discomfort. “They weren’t career people at all. They didn’t have vocations. My stepmother was a teacher for a while, she was a massage therapist for a while, she cleaned offices for a while. My dad worked at the state park for a while, he did building and contracting, he was a chef for a while, he baked bread for a food co-op. And now they both—I think they both work at Wal-Mart, I’m not sure. I know my dad does; I don’t know if my stepmother still does.”

Before he was born, his parents participated in a spiritualist organization called Subud. But they divorced when he was a year old, and Subud wasn’t prominent in the house as he grew up. (Stevens has written extensively in his lyrics about faith and his belief in God. In 2006, he released an elegantly reflective five-CD package, Songs for Christmas.) It wasn’t a household that especially nurtured creativity, either. Stevens says he had limited exposure to music other than “a lot of Top 40—really bad, white-bread pop radio.” When he was a teenager, his former stepfather, Lowell Brams, who now helps run his record label, introduced him to more adventurous music, like Nick Drake, Ry Cooder, and Kronos Quartet. Stevens studied classical oboe at the Interlochen Arts Academy in Michigan, but returned, discouraged, to public high school after a year. “I wasn’t very committed,” he says. “I grew tired of the fussiness of it. I knew I wasn’t good enough to pursue it professionally.” It was in college that he began working at music in earnest, learning guitar, piano, and banjo and constructing the kind of homemade songs that would eventually end up on his debut album.

What’s noticeably missing from Stevens’s sensibility is rock and roll. He isn’t one for gutsy directness or rough-hewn emotion. He’s a craftsman, a technician, a builder of ships in bottles. It’s significant that the first indie performer of his generation to make the leap to the big-league arts Establishment couldn’t care less about the defining popular music of the past 50 years. “Rock and roll is dead,” he says, voluble again. “Rock and roll is a museum piece. It has no viability anymore. There are great rock bands today—I love the White Stripes, I love the Raconteurs. But it’s a museum piece. You’re watching the History Channel when you go to these clubs. They’re just reenacting an old sentiment. They’re channeling the ghosts of that era—the Who, punk rock, the Sex Pistols, whatever. It’s been done. The rebellion’s over.”

So if rock and roll is dead, what’s classical? He laughs. “Mummified.”