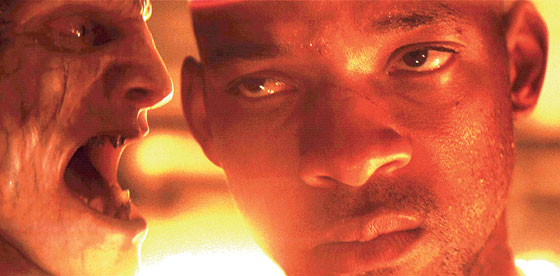

It’s an especially happy pipe dream during the holidays: midtown Manhattan depopulated but for deer, a few lions, and the congenial Will Smith standing in for all of us. Yes, there are hordes of hairless, feral vampires, but during the daylight hours they huddle indoors, leaving the hero of I Am Legend at liberty to drive like a maniac down empty avenues and shag golf balls from an aircraft carrier into the harbor, the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges (their middles blown out) a magnificent backdrop. He even has a companion—a loyal German shepherd named Sam. For quite a spell, we don’t know why Smith is the last human standing and don’t much care; we assume, correctly, that we’ll get traumatic depopulation flashbacks whenever the plot runs down. And as he proved in Independence Day and The Pursuit of Happyness, Smith is in his element cracking wise by his lonesome. His solitary existence isn’t as sad as it might be with more of a people person.

I Am Legend is the movies’ third stab at Richard Matheson’s novella of the same name. The Last Man on Earth (1964) featured a whiny Vincent Price besieged by zombielike bloodsuckers, while The Omega Man (1971) cast lockjawed Charlton Heston opposite hooded Manson-family-like albinos who wouldn’t shut up. (Led by Anthony Zerbe, they seemed more likely to bore you to death than eat you.) Neither film caught the nihilistic mood of Matheson’s book, in which the hero is as vicious and feral as the ghouls. This one doesn’t, either. Smith does grisly experiments on vampires in his basement, but he’s searching for a cure for their virus. Things only get personal when they go after his dog.

Apart from all the product placements, which feel weirdly incongruous in the context of Armageddon, the first two thirds and change of I Am Legend is terrific mindless fun: crackerjack action with gnashing vampires barely glimpsed (and scarier for that) and how’d-they-do-that New York locations that retroactively justify the traffic jams. (For a few weeks, every New York traffic report seemed to end: “And Fifth Avenue/lower Manhattan/Times Square is closed off for the Will Smith movie.”) The director, Francis Lawrence, clearly grooves on the visual gimmick—wide-open spaces alternating with claustrophobic dens, as Smith closes himself up in his Washington Square brownstone while the ghouls howl and moan outside. Then some boring characters show up and a dangling cross on a rearview mirror signals faith and hope are about to make a dispiriting comeback. The finale is swift and senseless. So far no one has gotten the ending of this story right. We should get on it before the real plague hits.

It doesn’t take long to see why Khaled Hosseini’s best-selling novel The Kite Runner hooked so many readers and critics who wouldn’t normally gravitate to first novels set in Afghanistan. It’s a redemption melodrama hinging on the idea that Islamic fundamentalists (in this case the Taliban) are, at heart, homosexual rapists. The narrator, having cowardly stood by as his doglike little boyhood friend (the son of his father’s servant) was buggered by bullies, has a chance to redeem himself by returning to Afghanistan (from the safety of San Francisco) to rescue the man’s son from being buggered by the same bully, who’s now wearing a turban and also busy stoning adulterers to death. Add bloody retribution and uplift—literally, in the shape of soaring kites—and you’ve got a story to please everyone, from world-history students to homophobes.

The new film directed by Marc Forster is brisk and bland, but its blandness might work at the box office, where movies in which little boys get raped don’t tend to pack in the crowds. (Gone Baby Gone never caught fire, even with all the acclaim.) It’s hard to find fault with Forster’s work. Although the western-China locations don’t match the wild-and-woolly Afghanistan of our imaginations, they’re perfectly acceptable, and Alberto Iglesias’s score gives Eastern exoticism a Western pulse. Khalid Abdalla plays the grown-up novelist hero, Amir, with just the right shade of wariness: You don’t hate him for wanting to work through his traumas on the page rather than with his fists—that’s who he is. As his brave, somewhat aloof father, Homayoun Ershadi has enough stature to survive David Benioff’s almost-too-efficient screenplay. (You can practically hear the stopwatch ticking—“Bring the movie in at two hours, boys!”) The only maladroit bit of dialogue comes when Amir’s wife (Atossa Leoni) receives the news that her husband is going to Afghanistan on the same day boxes with his first novel arrive: “Is it safe? What about your book tour?” (For some reason it made me think of Groucho’s “Will you marry me? Did he leave you any money? Answer the second question first.”)

The Afghan boys’ kite-flying contests are the emotional core of the film, and Forster and his crew bring the camera into the sky and make it dip and soar along with the kites. It’s a thrilling spectacle, although it’s also tinged with a peculiarly emasculating aggression: The goal is to wrap your string around your opponent’s string and cut off his kite.

Half the time in the mystical saga Youth Without Youth, I had no idea what the movie was about, but I always felt that the director and screenwriter, Francis Ford Coppola, did, and that he was deeply in tune—and having a hell of a time—with the material. He’s not whipping up another hyperkinetic whirligig like The Cotton Club or Bram Stoker’s Dracula. This time, his stationary camera drinks in medieval Romanian boulevards and the unruly landscape of the Nepalese border, and he lets the face and body of his brilliant leading actor, Tim Roth, convey the movement of a mind in torment.

Roth plays Dominic Matei, a depressed 70-year-old linguistics professor who gets half-incinerated by lightning, but as his body regenerates, the years fall off, and he’s suddenly a smooth and vigorous (and libidinous!) 40. He’s also telekinetic and can absorb books by passing them in front of his forehead. A Mengele-like Nazi scientist wants to see the master race similarly electrified, so our hero goes on the lam—accompanied only by a doppelgänger (Roth), who’s not a figment of his imagination and who pushes him to continue his search for the protolanguage that marked a cosmic leap in human consciousness. By luck, he bumps into the extraordinarily pretty Alexandra Maria Lara, who is promptly struck by lightning and then babbles in Sanskrit, Babylonian, and ancient languages not heard for thousands of years. I could go on with the synopsis, but I’d hate to deprive you of the chance to be mystified on your own.

Coppola was reportedly laboring in vain on a script called Megalopolis when a childhood friend turned him onto the work of the late Mircea Eliade, an authority on the history of Eastern religion. Youth Without Youth marks his return to the screen after eight years, and whatever you think about such topics as metempsychosis and love that bridges millennia, it’s a joy to see him engaged again by something besides Cabernet Sauvignon. Nearing 70 himself, Coppola takes a subject that once would have made him gaga and explores it with tenderness and lucidity. This is a movie about memory that is always in the present tense.

BACKSTORY

Though I Am Legend filmed all over New York City for six months, the most elaborate shoot took place over six nights in January, during which the 250-person crew—plus 1,000 extras, several tanklike vehicles, and a Black Hawk helicopter—took over the Brooklyn Bridge and its environs. At $5 million, it was reportedly the most expensive single scene filmed in the history of New York and required getting the permission of fourteen different government agencies.

I Am Legend

Directed by Francis Lawrence. Warner Bros. PG-13.

The Kite Runner

Directed by Marc Forster. Dreamworks. PG-13.

Youth Without Youth

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Sony Pictures Classics. R.