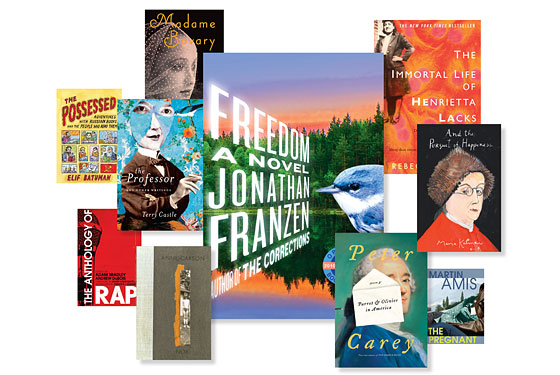

1. Freedom, Jonathan Franzen (FSG)

Franzen’s second juggernaut of the millennium is, admittedly (as its roiling crowd of detractors will tell you), not perfect. It has all his usual limitations: It’s cranky and formally old-fashioned, and its characters sound exactly like their author, especially when he wants us to believe they’re speaking for themselves. That said, it’s also great. Franzen’s achievements— the fusion of literary complexity and page-turning drama; characters who feel like actual humans—far exceed his limitations.

2. Nox, Anne Carson (New Directions)

One of the year’s most unusual reading experiences: a box full of grief, in all its complexity—fear, joy, anger, irony, despair, indifference. Carson, a poet and a classical scholar, treats her older brother, Michael (who died suddenly in 2000), like a mysterious figure from antiquity. In doing so, she makes an absence of nostalgia seem like the deepest possible tribute, animating faded old photos, injecting dictionary entries with sneaky poetry, and wringing improbable suspense out of Latin translation.

3.The Anthology of Rap, ed. Adam Bradley and Andrew DuBois (Yale)

This thrilling (but controversial) textual monument to a thrilling (but controversial) oral tradition wrestles the genre’s greatest lyricists out of the airwaves and into cold print. This means it excludes, obviously, much of what makes rap rap—voices, beats, hooks—but it also enables something wonderful: the ability to sit in perfect silence and roll around in, for example, the lush Keatsian soundplay of Jay-Z (“let the thing between my eyes analyze life’s ills”).

4. The Professor and Other Writings, Terry Castle (Harper)

It’s a familiar paradox: English professors, allegedly the world’s reigning experts on great writing, are some of the worst writers in the world. Terry Castle, a longtime Stanford professor, is mercifully immune to this cliché. She writes about art (Georgia O’Keeffe) and life (losing her virginity) in a big human stew of tones: goofy, analytical, slangy, raw, confessional. Her portrait of Susan Sontag, “the bedazzling, now-dead she-eminence,” is a comic masterpiece.

5. Parrot and Olivier in America, Peter Carey (Knopf)

Carey’s novel cranks its energy, like Don Quixote, out of the friction between two vastly different characters: a foppish French aristocrat (Olivier-Jean-Baptiste de Clarel de Barfleur de Garmont) and his rough English servant (John “Parrot” Larrit). The two men take turns narrating, and that counterpoint generates all kinds of comedy: They call each other names (“Lord Migraine,” “impossible villain”), contradict each other’s version of events, and finally end up unlikely friends.

6. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot (Crown)

Skloot uncovered, then spent ten years researching, one of the world’s great untold stories: the human origin of biology’s most famous cells—an undying strain, used in labs to help solve problems from polio to AIDS to cloning, known only as “HeLa.” Skloot returns these syllables to their owner: The cells were harvested from Henrietta Lacks, a poor black woman dying of cancer in 1951 Baltimore.

7. The Pregnant Widow, Martin Amis (Knopf)

It was a strong year for the comic novel: Sam Lipsyte’s The Ask, Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story, Paul Murray’s Skippy Dies. Few novelists, however, can match the charging comic energy of a reinvigorated Amis. The Pregnant Widow, his best book in fifteen years, is a meditation on—among other things—aging, bodies, sexual freedom, and the history of the English novel. (“Pride and Prejudice … had but a single flaw: the absence, towards the close, of a forty-page sex scene.”)

8. Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert, trans. Lydia Davis (Viking)

For 150 years, translators have been working to solve the riddle of Flaubert’s subtly powerful style. Results have been mixed. Davis, a fiction writer and acclaimed Proust translator, worked for years, with Flaubert-like meticulousness, to create the closest possible English version. (She even preserved apparent mistakes: irregular capitalizations, mismatched verb tenses.) Her version reminds us that Bovary, the official textbook of “realism,” is in fact deeply experimental.

9. The Possessed, Elif Batuman (FSG)

Batuman is obsessed with charting the strange angles at which literature—that reality-based abstraction—intersects with actual reality. In this collection of essays, she listens to Isaac Babel’s relatives squabbling with scholars at a conference (“Is it true that you despise me?” one keeps asking) and watches horses copulate in a field outside of Tolstoy’s house. Along the way, Batuman herself becomes a memorable literary character: smart, funny, charming, awkward.

10. And the Pursuit of Happiness, Maira Kalman (Penguin)

Inspired by President Obama’s election, Kalman spent a full year researching the history of American democracy. The result is an indescribable graphic-nonfiction-novelly thing: a road trip, a sketchbook, a grade-school history report, a love letter to Abraham Lincoln, and an art gallery bound between covers.