Legs McNeil never slept with Nancy Spungen, but he knew her. Everyone on the punk scene did. “There were only, like, 200 people,” he says. “So you met everyone pretty quickly. It wasn’t a scene that anyone wanted to be a part of. There was no velvet rope at CBGB.”

In the mid-seventies, McNeil was a staffer at Punk magazine, the snide but influential trash ’zine that gave the music its name, and Nancy was a groupie, trailing after the New York Dolls and the Heartbreakers. “Nancy had one of those passions for rock and roll that very few people have,” he says. “She knew everything about every album. Groupies in those days were different. They were a part of the scene. Everyone was treated the same. The roadies were treated the same as the rock stars. The groupies were treated the same as the rock stars. It was completely democratic.”

Nancy, set loose in New York City in 1975 at the age of 17, intuitively understood this delicate equilibrium. The punk scene was made up of outcasts, misfits, and social rejects; they all found each other on the Lower East Side and banded together. “We had an office called Punk Dump,” McNeil recalls. “It really was a dump. It was a storefront on 30th Street and Tenth Avenue, right under the el, where you go into the Lincoln Tunnel. There’d be these long traffic jams, and there’d be transvestites giving blow jobs to car johns from New Jersey who’d think they were women. We didn’t have a shower in the office, and Nancy would let us come over. She lived on Eighth and 23rd. It was a nice old basement apartment—I think her mother was paying for it. She’d make us scrambled eggs and talk.”

Sitting at a back-corner table in the courtyard of Yaffa Café on St. Marks Place—one of the few restaurants left in New York where he can smoke—McNeil, now 52, pulls another cigarette out of his pack and inhales deeply. “I liked Nancy,” he adds, a drip of sentimentality in his nicotine-rasped voice. “She could be very, very nice.”

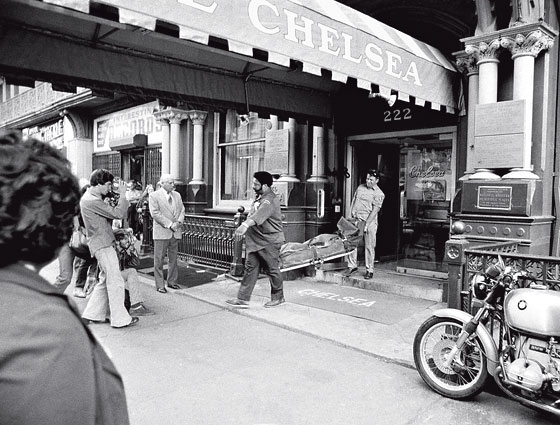

The words hang in the air, defiant, paradoxical. McNeil liked Nancy, the doomed sweetheart of Sex Pistol Sid Vicious who died 30 years ago this month in a pool of blood under a bathroom sink in the Chelsea Hotel; Sid, her accused murderer, OD’d four months later while awaiting trial, leaving her case forever unresolved. Nancy, the Times Square stripper and prostitute so reviled by Vicious’s bandmates that they banned her from their ill-fated twelve-day U.S. tour in 1978 (lead singer Johnny “Rotten” Lydon described her in his 1994 autobiography as “screwed out of her tree, vile, worn, and shagged out”); Nancy, a child so disruptive that her mother disavowed her in the 1983 memoir And I Don’t Want to Live This Life: A Mother’s Story of Her Daughter’s Murder.

Nancy Spungen doesn’t come up much anymore, and when she does, it’s as a rock-and-roll footnote, a tabloid grotesque wedged between the Son of Sam in ’77 and John Lennon’s murder in ’80. She resurfaced in the nineties as the role model for Courtney Love, the next generation’s peroxide parasite, arguably as reviled by the indie-rock scene as Nancy was by the punks. “She looked like Nancy Spungen … a classic punk-rock chick,” Kurt Cobain told Michael Azerrad in Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana.

McNeil’s unbegrudging compliment presents Nancy in something approximating three dimensions, something more than a cultural cipher and a groupie from hell. Something more than the female half of Alex Cox’s 1986 losers-in-love saga Sid & Nancy, which portrayed Nancy staggering through the streets in search of a score, screeching “Siiiiiiiiid!” in an impossibly grating voice, while her beau crashes through glass doors and nods out in burning hotel rooms.

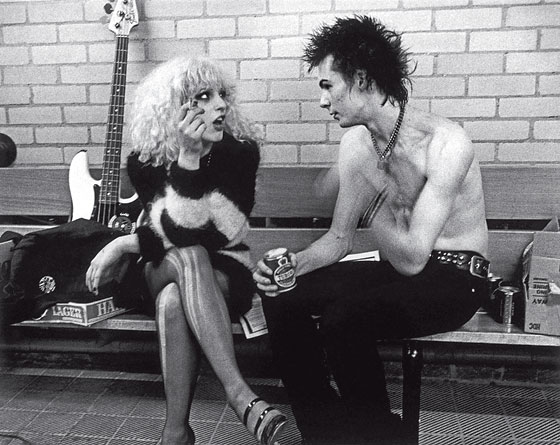

The real Nancy was prettier and softer than Chloe Webb, who portrayed her in Cox’s film. You can find a series of grainy black-and-white clips of her on YouTube, from an obscure New York cable talk show taped less than a month before her death on October 12. You’re struck by how shockingly close to adolescence she was, chewing a wad of gum and self-consciously flipping her hair; she was only 20 when she died. Sid is next to her: At one point he removes his leather jacket, nearly clocking her in the face with his elbow, as if he’s forgotten she’s there. Seated next to him at a long table are Stiv Bators of the Dead Boys and Cynthia Ross of the B Girls. They’re here, presumably, because punk has been building momentum. Though the Sex Pistols imploded after their disastrous U.S. tour, the biggest bands nurtured in the CBGB scene—Television, Patti Smith, the Ramones, Talking Heads, Blondie—all have record deals, though none has yet scored a hit. Vicious, Bators, and Ross are there as emissaries from a scene the larger world—New York above 14th Street—doesn’t yet understand. Nancy isn’t introduced at the start of the segment. She’s not in a band and clearly doesn’t count.

But of the four of them, she’s the only one up to the task of serving as a spokesman for and defender of punk rock. As a shirtless Sid belches and flicks boogers, and Bators and Ross mumble and pout like eighth-graders in detention, Nancy fends off a series of live callers whose remarks range from insulting to deranged to incendiary. “In England, almost the whole business is punk,” she retorts to one caller who claims that punk rock is on the decline. “You should have seen the year-end polls in the newspapers. The Pistols swept all the polls. They got best new group, best album, best live group, best guitarist, best drummer, on and on and on.” She scowls when another caller dismisses Sid’s music as “derivative.” “He’s about as original as you can get,” she snaps. “He’s not derivative of anything. If you don’t believe me you can ask the old-wave musicians in England, because they believe the same thing.”

“I think Sid is hot,” purrs a sultry female voice.

“Well, you better keep your fucking hands off him, dearie, or I’ll kill you,” Nancy replies.

Another woman calls in. “Sid Vicious is a spoiled brat,” she snarls. “And his girlfriend—”

“What about me, duckie?” Nancy answers, coiled and ready.

“You’re an asshole, ya blonde bitch,” the caller says.

“Oh, yeah? Come here and say that,” Nancy says.

“You’re an asshole!” the woman yells.

Sid, who’s been sitting there with a hangdog expression, finally rouses. “Not as much of an asshole as you are, you fucking cow!” he bellows.

“Cow!” adds Nancy. But she’s smiling. She loves a fight. She settles back into her chair, fluffing her hair again. “You jealous or something? Huh? Oh, I bet you’re so jealous, sweetheart.”

Loud, yes. Obnoxious, yes. But that was the point. The first wave of punk directly confronted a culture it despised. And Madonna hadn’t come along yet to turn bitchy aggression into an art form. “You’ve got to remember, Donny and Marie were on TV,” says McNeil. “We were tired of being nice. It was like, fuck you. The left had become as oppressive as the Republicans. They invented that political-correctness stuff. Punk was supposed to piss off everybody and make people think.”

Nancy was no more messed up than anyone else on the scene, says Legs McNeil. “Joey Ramone pulled a knife on his mother. We were all a little disturbed.”

If you believe Deborah Spungen’s memoir (the Spungen family declined to be interviewed for this article), Nancy devoted her life to pissing people off. Born in 1958 and raised in the Philadelphia suburbs, she was difficult from birth: impossible to console, prone to tantrums, hostile, insatiable, demanding, and a bully to her younger sister and brother. “A 7-year-old ran our household,” Deborah writes. “When she wanted something, no matter how big or small, she hollered and screamed and backed us into a corner until we were the ones to back down. We gave in to her. Why? Because there was absolutely no peace in the house until she got what she wanted.” When she was a bit older, Nancy attacked her mother with a hammer. The family brought her to a succession of doctors, psychologists, and clinics; at 11, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, although Deborah says the doctor didn’t disclose the diagnosis to the family. At one point, Nancy was committed to a mental hospital, then sent to a boarding school for troubled kids, before arriving in New York City at the age of 17. By that point she was already taking drugs and sleeping with musicians. “It seemed as if every week she got wilder, further and further from our control and our sense of right and wrong,” Deborah writes. “Our morality meant zero to her. She would simply step over the line, draw a new one, and then step over that. We were also revolted. It was ugly and distasteful and we hated to see such a bright child throw her life away—trash it, really. But we were powerless to stop her.”

Nancy’s New York friends feel that her intense discord with her family factored deeply into her problems. “Like most kids who are 17, basically her statement was, ‘I hate my family,’ ” says photographer Eileen Polk, who hung out with Nancy at clubs and parties. “All the things that she loved and thought were important in the world, they told her were stupid. I think she had a really stifling middle-class upbringing.”

But as McNeil points out, punk—like any great rock-and-roll movement—would be nowhere without repressive, disapproving parents. “Nancy was no more fucked up than anyone else on the scene,” he says. “She wasn’t any more fucked up than Dee Dee [Ramone] or me. Joey [Ramone] was paranoid schizophrenic. Joey pulled a knife on his mother. We were all a little disturbed.”

From the time of her arrival in New York, Nancy used drugs to meet musicians. “She was blatantly honest about it: She bought drugs for the bands,” Polk says. “She was honest about being a prostitute as well, which I thought was refreshing. The punk scene, like any other scene, had its little hierarchies. There were groupies that had been around for a long time because of their looks. In order to be a groupie you had to be tall and skinny and have fashionable clothes. There were a bunch of girls like that on the scene. And then here comes Nancy. She’s not trying to be cute or charming. She wasn’t telling people she was a model or a dancer. She had mousy brown hair and she was a bit overweight. She basically said, ‘Yeah, I’m a prostitute, and I don’t care.’ ”

But Nancy was too extreme even for a movement centered on extremeness, and she never gained the acceptance she craved; she was an outcast among outcasts, nicknamed “Nauseating Nancy” behind her back. “It was jealousy,” says Roberta Bayley, who worked the door at CBGB. “There’s no more competitive thing than who can fuck these musicians. Maybe Pamela Des Barres tells the story of female solidarity, but there was a lot of backstabbing.” According to Polk, “The other girls shunned her and were mean to her. And that made Nancy worse. She became vengeful. She kind of reacted to them putting her down by doing even worse things. The only people who didn’t shun her were the guys that were getting drugs from her.”

By the spring of 1977, Nancy had “worn out her welcome,” says former Dead Boys guitarist Cheetah Chrome. She took off for London, following Heartbreakers Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan, but even her reliable targets were tiring of her. London scenester Bebe Buell says Nolan (who died in ’92) tried to shake Nancy: “I remember Jerry saying to me, ‘If this chick Nancy Spungen tries to find me, please don’t tell her where I’m staying.’ He was trying to dodge the bullet.”

Then Nancy found her twisted Romeo. Working-class, musically challenged, highly impressionable, and enamored of the New York punk scene, Sid Vicious was the bass player for the biggest band in England, and already the walking epitome of punk nihilism. “If Rotten is the voice of punk, then Vicious is the attitude,” Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren famously decreed. Both knew no limits. Photographer Bob Gruen accompanied the Pistols on their U.S. tour. “I remember talking to Sid on the bus, and he really seemed to care for her,” Gruen says. “He didn’t have any anger or hatred toward her. Sid very much loved Nancy. They seemed to communicate and connect.”

“I was there in a club when some girl offered Sid her number,” says Victor Colicchio. “Nancy said, ‘Push her down the stairs.’ And he did. He was a knight in rusty armor.”

But the Pistols broke up at the end of their American tour. Back in London, Sid attempted a solo career, with Nancy now calling herself his manager; by the end of August 1978, they returned to New York, moving into the Chelsea Hotel. “When she came back with Sid, it was like she had triumphed,” says Polk. “She had shown everybody that she really had what it took to become this famous groupie. Some people were outraged by it. They just couldn’t believe that she had succeeded in her quest.”

Victor Colicchio, an actor, screenwriter (Summer of Sam), and member of a short-lived seventies band called the Dead Squirrels, also lived at the Chelsea. He saw Nancy’s good side, despite her spiraling drug problem. “She was highly intelligent and very aware,” he says. “She could spot someone conning her a mile away. She had good insight into people. She was aware of phonies and fakes and users. She did display that wild, crazed behavior, but it wasn’t her total being. I saw both men and women pushing past her, not acknowledging her, talking to Sid. I think a lot of her nastiness and temper tantrums were rooted in that. I was there one night in a club where some girl offered Sid her number. Nancy said, ‘Push her down the stairs.’ And he did, without a second thought. He was a knight in rusty armor.”

By this time, the drugs were taking over. There’s a famous clip of Sid and Nancy from the 1980 documentary D.O.A. Sid’s nodding off, and Nancy’s snapping at him to wake up. “They’re like the Honeymooners,” says Roberta Bayley: “ ‘Wake up, you knucklehead! We’re on TV!’ It’s so sad, it’s funny.” Even the hard-core drug users began to avoid them. “Sid and Nancy as a couple were going down the toilet, and everybody could see it,” says Television guitarist Richard Lloyd. “To hang out with Nancy and Sid was to make a grievous mistake for your own health. I took lethal doses of everything known. You couldn’t call the kettle black. Mine was jaw-droppingly black. But I’m still here. They’re not.”

Nancy died early in the morning from a stabbing. The details of that day are ensconced in legend. At 2:30 a.m., Nancy begged actor and addict Rockets Redglare to score them some Dilaudids. Female moans were heard coming from the room before 7:30 a.m. Vicious called the front desk about 10 a.m., asking for help. Early that afternoon, he would be arrested for her murder, apparently having confessed to the police; they never seriously considered another suspect. But all these years later, no one I spoke to believes he killed her. “I think when Sid awoke stoned out of his mind and realized she was dead, he might have assumed he did it,” says Polk, explaining the confession. Everyone has a different theory: drug deal gone awry, robbery, or just a mistake that came from having too many knives around. Bassist Howie Pyro, who was with Sid the night he died, believes Nancy might have been so desperate for attention that she stabbed herself, thinking Sid would come to her rescue, but that he was too stoned. Nancy’s wound wouldn’t have killed her if it had been attended to promptly, but Sid had gobbled fistfuls of the barbiturate mix Tuinal. “In my opinion, he was a little on the henpecked side,” says Colicchio, in and out of the room that night. “I don’t think he would’ve killed her unless she told him to.”

Nancy’s death remains an intoxicating subject, swirling in mysteries that will probably never be unraveled: British author Alan Parker, who has written books about Sid, is currently in production on a documentary called Who Killed Nancy?, due for release next year. But what everyone agrees on is that her death—and Sid’s overdose four months later—was a horrible symbol that hobbled the scene almost beyond repair. “It was like the Manson family in the sixties,” says McNeil. “It killed punk overnight. We were doing the Punk magazine awards. Lou Reed was there, everyone was there. All the camera crews were there, and they just wanted to talk about Sid and Nancy. It was disgusting.”

“There was a lot of hope at that time,” says Colicchio. “The music was catching on, bands like Talking Heads were breaking out. A lot of us were thinking, Hey, we may not have to get regular jobs. A lot of it hinged on Sid. He seemed to be the last one carrying the torch. When he died, we all felt like it was over. A couple of bands didn’t even want to gig. What was shunned was now persecuted. It was almost as if the war was over and we’d lost.”

The original punks only lost the battle. Ten years later, punk was on the upswing again, still fringe music and mildly dangerous, but with a muted tone. Bands like Sonic Youth, the Replacements, and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds thrived on apathy and neglect instead of hatred. In the early nineties, Nirvana finally broke punk to a wide audience. But winning the war changed everything. Today punk is a worldwide brand, predictable, devoid of significance. You can imagine Nancy’s reaction: Winners suck.

Legs McNeil doesn’t live in New York City anymore. He bought a house in rural Pennsylvania and doesn’t relish his return visits. He’s now a recovered alcoholic wearing a black Hawaiian shirt decorated with pictures of exotic cocktails and pegged black jeans 30 years out of fashion. He wants his old New York. He glances at a girl in slutty Sex and the City clothes that aren’t slutty anymore, talking on her cell phone while her dining companion gazes patiently into space. The sight brings out a little of his old fire. “I don’t know who the fuck they’re talking to,” he sneers. “Are they talking to other people in restaurants eating breakfast?” Where’s Nancy when you need her? She would have hated it here. She wouldn’t have lasted a minute.