Ramone died in 2004. This article is adapted from Commando: The Autobiography of Johnny Ramone (Abrams Image; April). © 2012 Johnny Ramone Army LLC.

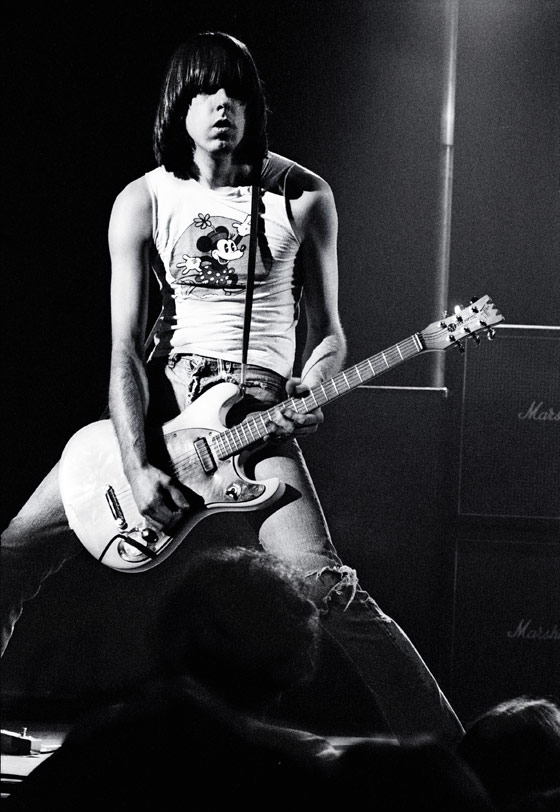

For all my success with the Ramones, I carried around fury and intensity during my career. I had an image, and that image was anger. I was the one who was always scowling, downcast. I tried to make sure I looked like that when I was getting my picture taken.

When I was younger, I was ready to go off at any time. My wife, Linda, and I would go out to the Limelight in New York, and I would see people and be able to freeze them with a look. People were even too scared of me to tell me that people were scared of me.

I never felt out of control. It was just the way I lived my life. I was the neighborhood bully. I even beat up Joey, our singer, one time, before we were in the band. He was late to meet me—so I punched him. I was 21; he was 19. We were meeting up to go to a movie. There was no excuse for being late.

Tommy, Dee Dee, and I would go out to the clubs, which is really how the band got started. We were all friends. We had the same musical tastes, and we liked to get dressed up. Those were in the glitter days.

We lived in Forest Hills, and my parents were working class all the way. My father was from Brooklyn, he had three brothers, and they were all tough guys. They’d sit around our kitchen table and drink and talk about things like construction work and baseball. So, with all that macho stuff, they weren’t all that happy when I started to get really into music.

Tommy, Dee Dee, and I would go hang out at this place on Bleecker Street called Nobody’s. One night, the New York Dolls were hanging out there. They were already a band, but I hadn’t seen them yet. I pointed to Johnny Thunders and told Tommy that he looked cool. Tommy said that the band was terrible. But I knew, looking at him, that there was something there. To me, it’s always been about the look.

Tommy really wanted us to form a band, and he would be manager, and it would be this primitive thing. I’d say, “Oh that’s ridiculous, I want to be normal.” But he kept bugging me, and finally it turned into “Oh, now I have to actually do it?”

I wasn’t a rock star, but I liked to dress well. I was six feet tall and weighed about 150 pounds, so I could wear a lot of things. I didn’t spend a lot of money on clothes, but would always find stuff I thought was cool. I would get my clothes made at Granny Takes a Trip. I would have them make me velvet suits; I wore snakeskin shoes, chiffon shirts. I was working a construction job, and my life was putting on my jean jacket and going to work with all these union tough guys, then going home, changing into whatever clothes I was into at the time and driving into the city to see a show.

I went through phases. In high school, I always looked toward Brian Jones to see what he was wearing and then tried to find the closest thing. I thought he was one of the best dressers in rock and roll. Corduroy pants and corduroy shoes and striped shirts and striped T-shirts. There was a two-year period where I would wear jean jackets with no shirt, jeans, a tie-dyed headband, and a tie-dyed scarf around my waist. I always wanted to be the best-dressed person anywhere I went.

We were a three-piece, and it was bad. Dee Dee still couldn’t sing and play at the same time. As Dee Dee and I were getting better on our instruments, Joey kept getting worse. Tommy said we needed more rehearsing, but I realized that Joey just wasn’t right. I said, “Tommy, we need to get rid of Joey. He can’t play drums.” But Tommy said, “No, he can be the singer.” I wanted a good-looking guy to be the singer. But Tommy said, “No, it will be like Alice Cooper. It’ll be good.”

At that point, we were still dressed in partial glitter. I had these silver-lamé pants made of Mylar, and these black spandex pants I’d wear, too. I was the only one with a real Perfecto leather jacket—what the Ramones would later be identified with—which I had been wearing for seven years already. I also had this vest with leopard trim that I had custom made.

We were still evolving into the image we became known for, but it was trial and error at first. I’d give Tommy a lot of the credit for our look. He explained to me that Middle America wasn’t going to look good in glitter. Glitter is fine if you’re the perfect size for clothes like that. But if you’re even five pounds overweight, it looks ridiculous, so it wouldn’t be something everyone could relate to.

It was a slow process, over a period of six months or so, but we got the uniform defined. We figured out that it would be jeans, T-shirts, leather jackets, and the tennis shoes, Keds. We wanted every kid to be able to identify with our image.

Some bands blow it before they even play. The most important moment of any show is when a band walks out with the red amp lights glowing, the flashlight that shows each performer the way to his spot on the stage. It’s crucial not to blow it. It sets the tempo of the show; it affects everyone’s perception of the band.

Now all the mental notes I had been taking over the years came into play. No tuning up onstage. Synchronized walk to the front of the stage and back again. Joey standing up straight, glued to the mike stand—for the whole set. Keeping it really symmetrical. It was a requirement we adopted, a regimen that started immediately when we’d hit the stage, to make sure you immediately go into the song and not lose that excitement before you even start.

I’ve always thought you’re better off playing shorter. Ramones songs were basically structured the same as regular songs, but played fast, so they became short. When I saw the Beatles at Shea Stadium, they played a half-hour show. I figured that if the Beatles played a half-hour at Shea Stadium, the Ramones should only do about fifteen minutes. You get in your best material, and leave them wanting more. I don’t think anyone should play for more than an hour.

I mostly went to our shows alone. I’d go out to CBGB and I’d think, “I’m surrounded by a bunch of assholes.” People thought I was unfriendly, but I wasn’t. I just didn’t like the people I was around. I didn’t have anything in common with them. We were working; CBGB was where I worked. When I was a construction worker, I didn’t hang out with those guys after work either.

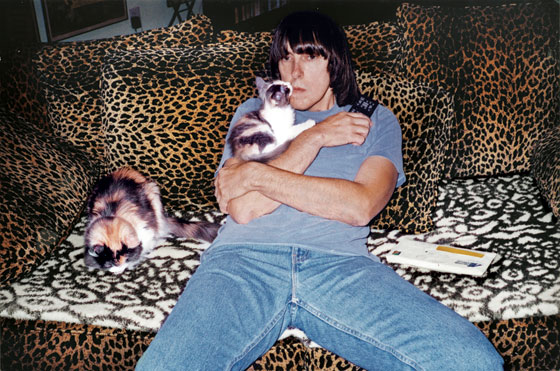

Rock and roll is an unhealthy lifestyle. You have too much freedom, and there is a lot of pressure to produce. People who don’t know how to handle the situation take drugs. I didn’t. I went back to my room with milk and cookies. The fans lined up outside the nearest 7-11 in any city we played, knowing that the Ramones van was going to head over there right after the show. I wanted to get back to my room and watch SportsCenter on ESPN.

When we started, I believed that if you were good in this business, you would succeed. But it doesn’t work that way.

We wanted to save rock and roll. I thought we were going to become the biggest band in the world. I thought the Ramones, the Sex Pistols, and the Clash were all going to become the major groups, like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and it would be a better world. It would be all punk rock, and it would be great.

There was a big hype about punk rock taking off, but it didn’t happen. In England, they promoted punk rock, and everybody had some hits. Promotion was what it took, and that never happened in the United States. We turned to Phil Spector as a last resort to get played on the radio.

Spector had been after us for a while: “Hey, you want to make a great album?” Right from the start, he was abusive to everybody around him except us. He was also painfully slow. This was not how I was used to working. I didn’t want to be living in a hotel for two months doing a record.

Spector would make us think we were going to change studios every day, so we never knew where we were going in advance. At the end of each session he’d say, “I’m not sure what studio I want to use, so call me tomorrow and I’ll let you know.” But we never moved. We’d be at the same place every day, Gold Star Studios. We’d call and he’d say, “Okay, we’ll be at Gold Star.” Yeah, that’s what we thought, since that’s where our equipment was set up, but for some reason he always wanted us to think we might move. He was crazy. He’d scream at the engineer. He never ate and never slept. We suspected he was doing cocaine. One day, our soundman came by, and Phil started in, “Who the fuck are you? Why are you here?”; the same thing over and over, for half an hour. We said, “Phil, this is our soundman.” But he wouldn’t stop. “Who do you think you are anyway? You’re nobody.” It was awful how badly he could treat people.

After a couple of days, I reached the breaking point. He had me play the opening chord to “Rock ’n’ Roll High School” over and over. This went on for three or four hours. He’d listen back to it, then ask me to play the same chord again. Stomping his feet and screaming, “Shit, piss, fuck! Shit, piss, fuck!” I couldn’t take it anymore. So I just said, “I’m leaving,” and Phil said, “You’re not going anywhere.” I said, “What are you gonna do, Phil, shoot me?” Here’s this little guy with lifts in his shoes, a wig on his head, two bodyguards, and four guns—two in his boots and one on each side of his chest. After he shot that girl, I thought, “I’m surprised that he didn’t shoot someone every year.”

The album End of the Century turned out to be good, but we didn’t have a hit. It charted in England, No. 8 or something, but who cares about England? We were American.

I’ve always been a Republican, since the 1960 election with Nixon against Kennedy. At that point, I was basically just sick of people sitting there going, “Oh, I like this guy. He’s so good-looking.” I’m thinking, “This is sick. They all like Kennedy because he’s good-looking?” And I started rooting for Nixon just because people thought he wasn’t good-looking. And then by the time Goldwater ran and he starts talking about bombing Vietnam, I said, “This sounds right to me.” I was in favor of bombing the enemy into oblivion. Same as any war: If you want to be in it, win it. I didn’t understand why we didn’t just bomb the place out of existence.

At the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, when I made my acceptance speech I said: “God bless President Bush, and God bless America.” That sure set them off. This wasn’t long after September 11—I was always so gung ho American, I felt that was a real attack on me.

One of the things I am most proud of that we did was a benefit at CBGB for the New York Police Department so they could get bulletproof vests. This was when New York wasn’t safe at all, before Giuliani fixed it up. We even had protesters outside the club, those commies.

The most unlikely place I was ever recognized was on the trading floor of the Stock Exchange. I walked down there and everybody knew who I was. They were handing me phones and asking me to say hello to their friends. I talked to everybody. That was in the nineties. I thought, “All these Ramones fans work on Wall Street?”

The band trusted me to get them as much money as I could, and we did fine. They never said a word to me about it or questioned me. I would say, “Money is our friend. It doesn’t do anything to you. It is good.” I used to say that all the time.

We made money over the long run while we were still together. I think that when we really got going, we paid ourselves a $150-a-week salary. When we came back from a tour, we each would get another $1,000. And then we started getting merchandise money, which was more than our regular salary. I was trying to watch the money. I figured if I could save a million dollars, I could retire. We weren’t getting rich, any of us.

Anheuser-Busch approached us in 1994 and bought a song for a commercial. I thought it was terrific. I liked seeing the commercial, and people would ask me how I felt about it, and I would tell them it was the easiest money I ever made. I never looked at it as anything bad. Sometimes something like that can be lame, but for beer, which is very American, it’s good.

I made more money after we stopped than I ever did while the Ramones were active. We made a lot of money from merchandising, and the records sold better than ever. Maybe everyone really does love you when you’re dead.

See Also

• Johnny’s Obsessive Collection of Top-Ten Lists

• Johnny Grades Every Ramones Album