Julian Casablancas is at an impasse. The front man of the Strokes, that garage-rock power quintet whose masterful 2001 debut, Is This It, was named album of the decade by both Chuck Klosterman and the British music magazine NME, is gently haggling with a hostess at Momofuku Noodle Bar. She is insistent that the New York native leave his electric guitar and silver suitcase full of stage props unattended at the front door. (Hostess: “We can keep an eye on it for you.” Casablancas: “Uh, sorry, no.”) Granted, this particular challenge seems minor compared with the sticky situations Casablancas has had to navigate since the Strokes seemingly imploded last year and he felt he had no choice but to put out a solo album. But it follows a familiar theme: Casablancas getting stuck between what he knows he wants to do and what he feels like he has to do to deal with other people.

The hostess reluctantly finds a corner for his stuff and a perch from which he can watch it, and Casablancas apologizes once again: “I’m sorry. I just didn’t want to leave it there. It’s New York.”

Momofuku was an afterthought. We’d first met up at Waverly Restaurant, a spot Casablancas had supposedly chosen. After about a minute of looking warily at the menu (“This is diner food, I’m assuming?”), he admitted that he’d actually been craving ramen, but had been too polite to resist his publicist’s orders to go to Waverly. We dashed out—although not before Casablancas had left a wad of crumpled bills on the table to assuage his guilt.

Over his coveted bowl of pork ramen, which he declares “delicious” if perhaps overpriced at $16, Casablancas says he’s still in “touring haze” from some whirlwind gigs in Europe. Before that, he’d been in Los Angeles recording his solo debut, the intricately composed, keyboard-heavy, and critically praised Phrazes for the Young. He did the album on the cheap, but then poured his own money into a four-show L.A. trial run of a staggeringly ambitious stage show complete with costume changes and elaborate sets. The video backdrop for one song, “Ludlow St.,” began in the desert and ended in skyscrapers, tracing the evolution of New York City along the way. The shows were a fiasco, and he promises the tour’s final dates, January 14 and 15 at Terminal 5, will have “none of that. In the end, it wasn’t a positive experience for me at all,” he says. “It was a constant struggle with the venue, managers, lighting guys, video people. I went broke doing it.” And yet he’s already taking meetings to fix what went wrong. “I want to do that in New York eventually. Badly.”

Even with his two Terminal 5 shows pared down, Casablancas sounds weary from the preparation. “I’m just busy with bullshit,” he says. “Working on music is the funnest thing for me, and I love it, and I could do it all day, all night. But there’s all this other crap that I just constantly have to do. I don’t have time. I don’t like the business side so much, but it’s a necessity because I also don’t like the way other people do the business side for me.”

Everything in Casablancas’s long, hard year as a soloist has carried a steep learning curve, from touring by himself to getting the album into stores. For example, RCA is co-releasing his solo album, yet, he says, “they’re not the label I signed with. The people change all the time. They’re nice, they’re cool, but honestly they don’t do shit.” So he did most of the work through Cult Records, the label he started for Phrazes and financed himself, and it didn’t turn out much better. “You have all these dreams. I still like the plan, but it was executed terribly.”

And then there’s the Strokes. Theoretically, they are putting out a fourth album. “It’s coming!” he says. The band had made it all the way into the studio this past summer and then stopped abruptly, allegedly because guitarist Albert Hammond Jr. had to go to rehab. Casablancas has already been vocal about his dissatisfaction with the way the band has been run. “We split the money six ways”—manager Ryan Gentles gets the sixth share—“but we didn’t split the work,” he says. The Strokes, he adds, were never the carefree gang of five they seemed to be to the world—the perfect postadolescent posse consumed with partying, making music, and traveling the world. “It was nothing like that.” he says. “It was really, really hard.”

Casablancas looks uncomfortable. He says he’d rather focus on what’s going right with the Strokes. “I understand people are interested, but it’s very different than before,” he says. “It’s night and day now. Everyone is working as a group, ‘Let’s do it! Go team!’ Which is amazing. Which is what I wanted since day one. But that’s only happening now. Literally now. So if I make it super-clear why I was unhappy in the past, it might just rehash things that should have been left alone. I think we’re fulfilling the promise of what we said we were: actually being a unit that really works on everything.”

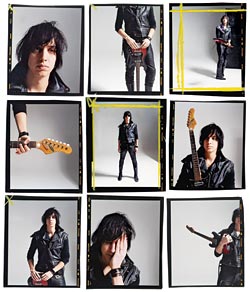

Casablancas’s tall frame is hidden under layers of shirts and sweatshirts, and he is so pale that one fears for his skin in the sun. (“Sometimes I’ve sat outside, not to tan, but as a result of that I ended up tanning slightly,” he offers.) Over ten years and three Strokes albums, the press has portrayed him as the boozing, disaffected epitome of rock and roll, as well as everything that’s still cool about New York—aided in no small part by his seventies shag haircut, a wardrobe of leather and velvet, and, until recently, a lot of public intoxication. In fact, he’s more Edward Scissorhands than Iggy Pop, equally vulnerable and optimistic, and laboring under a persona he’s clearly outgrown. “It almost would’ve been more fun if I hadn’t been drunk,” he says. “I remember the hangovers better than the time I was drinking.” Those days are over. “Some people can drink casually. I envy them. If I have one drink in me or two drinks in me, I just don’t have the willpower to stop anymore.”

At 31, Casablancas is now a family man. Five years ago, he married the band’s then–assistant manager, Juliet Joslin. When he’s not making music, they hang out with their two dogs, Balki and Voltron, named for the Perfect Strangers character and the eighties cartoon, respectively. Marriage, he says, feels “pretty natural,” even though he hadn’t planned to get hitched so early. “I guess I never thought I’d meet ‘the person,’ but I don’t find it weird. I find it great.” Casablancas is equally enthused—and somewhat freaked out—by becoming a father (his wife is due next month). How does that mesh with rock stardom? “The idea of being a rock star is never something I’ve thought of anyway,” he says. “In most cultures, you can have a kid at 18 and it’s not a big thing. It’s not like, ‘Oh, you’ve got to get a different haircut and move to the suburbs and act, like, 35.’ I don’t get that mentality. I’m trying to enjoy the time before it because I know that everything is going to change. You’re just trying to make this little life survive.”

Given his own tempestuous youth, he’s aware of the challenges. Casablancas was a bit of a terror growing up, sneaking out late and drinking forties in the park. He was raised by his mother, former model Jeanette Christiansen, who divorced his father, John Casablancas, founder of Elite Model Management. But he can’t imagine bringing up a kid anywhere else. While recording out West, he briefly flirted with the idea of moving to L.A., wooed by blue skies and his love of driving the ’92 Cutlass he bought for $1,000. “L.A. is a vortex. The weather there tricks you into thinking you’re on vacation, even when you’re working fourteen hours a day,” he says. “But when I came back, I was like, ‘Whoa! What the hell was I … I’m glad I got out of there.’ ”