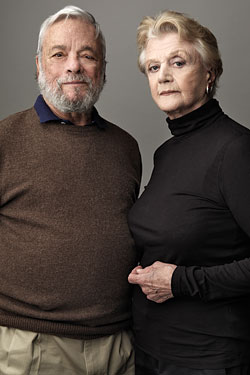

Actors are often slaves to authors, or at any rate authors are often dictatorial toward actors, but Angela Lansbury, 84, and Stephen Sondheim, 79, have had a rare theatrical relationship, in a way helping each other create, or reimagine, some of the landmark musicals of the past 45 years: the 1964 cult flop Anyone Can Whistle; the great revival of Gypsy in the seventies; Sweeney Todd in 1979; and the just-opened revival of A Little Night Music, directed by Trevor Nunn and co-starring Catherine Zeta-Jones. On the morning after the first preview, Sondheim and Lansbury—he weary from the previous night, she chipper and ready for rehearsal—sat down at Sardi’s to discuss their collaboration. It began when Arthur Laurents, who was directing Anyone Can Whistle, as well as writing its book, suggested casting Lansbury in a leading role, despite not knowing if she could sing.

Angela Lansbury: I received a thin blue envelope with a thin blue piece of paper inside, like toilet paper. It was a very nicely handwritten letter from Arthur, asking if I might be interested in auditioning for the part of Cora the Mayoress. The idea of being in a musical thrilled me!

Stephen Sondheim: You’d done the film The Harvey Girls, but they didn’t use your voice. So you hadn’t actually sung with an orchestra in a movie, had you?

A.L.: No, but you’ve forgotten that after leaving London during World War II, I began my professional career in cabaret—in a Russian nightclub in Montreal called the Samovar. I sang a lot of Noël Coward, and an arrangement of “I Went to a Marvelous Party” with coloratura, contralto, mock German. I had ideas of singing, but it was always a character singing, never straight singing.

S.S.: Did you have eyes on a club career?

A.L.: No! I’d just come out of drama school, I was 16 years old, and I needed to work because we had no money. When I got the job, I lied about my age and went up to Montreal. I don’t know how I had the gall to think I could do this.

But by the time you got the letter from Mr. Laurents, you were a movie star with two Academy Award nominations. Weren’t you too established to audition for a strange musical by a not-very-well-known composer?

A.L.: No. The theater always came first. Movies were incidental. So I was happy to audition. I sang “A Foggy Day in London Town.”

You took the role but soon discovered you weren’t completely taken with it. After all, Cora was not exactly a realistic character: the evil mayoress of a bankrupt town who fakes a miracle to attract tourists. Did you try to improve it?

A.L.: I’d like Stephen to take that question.

S.S.: Angie came over one afternoon while we were in rehearsal and said, “Cora is a cartoon, and I don’t know how to play a cartoon. I’m not that kind of performer.” I said, not bluntly, “You read the script and you knew she was a kind of Kay Thompson substitute—the whole idea is that her heartlessness and banality would be reflected in my heartless, jazzy nightclub numbers.” She had trouble with that—I’m putting words in your mouth, Angie—because there was no there there. I didn’t know what I could do about that, but then she added, “And Lee [Remick, the other female lead] has five songs while I have four.” I said: “That I can solve.”

You weren’t above a bit of number-counting?

A.L.: I’m surprised that I wasn’t, but … yes.

S.S.: So I wrote “A Parade in Town,” which has some weight to it and is a solo, giving the audience a chance to see Cora alone.

A.L.: It showed this very layered woman and gave me emotional heft, which the part did not have before. It was a special thing he gave me, and I think the reason we’re sitting here today is because back then he recognized in me a person who could deliver this kind of song in the way it was intended.

Stars do have to be deployed carefully to meet audiences’ expectations. Is there a way in which that’s not just smart for them but for the architecture of the piece?

S.S.: Yes, except sometimes it backfires. I thought if you’re going to see a show with two movie stars, you’d like to see them do a duet, so I devised “There’s Always a Woman.” It lasted one performance. It was an eleven o’clock number, but at that point in the evening, it already seemed like 11:30.

The tryouts in Philadelphia seemed cursed. Henry Lascoe, who played one of Cora’s henchmen, died; a musician in the pit died, too. And apparently Miss Lansbury felt she was dying onstage.

A.L.: I was insecure and unhappy because I did not want to play the role the way Arthur wanted to direct me—he knows this, I’m not talking out of school. I remember standing at the top of the stairs in the theater in Philadelphia and shouting, “I don’t know what you want, and I can’t do it!”

S.S.: And I remember how frightened I was. I thought, “She’s going to quit, she’s going to quit.” But something happened that restored your confidence.

A.L.: Audience reaction—simple as that. Now, I’m not a big audience-chaser. I don’t try to please them; I force them to pay attention to what I’m doing, and get them that way.

The role established you in the musical theater, even though the show ran for only nine performances on Broadway.

A.L.: Although 90,000 people apparently saw it.

S.S.: Closing night, I was in the wings when Angie was about to be carried in on a palanquin by four guys for her first entrance. She said to them, “Okay, let’s give ’em hell.” I cried.

She’d been through the London Blitz—she’s a trouper.

S.S.: And she’d been through Arthur.

You didn’t work together again until the revival of Gypsy. By then, Miss Lansbury, you had carried major musicals—Mame and Dear World—and won two Tonys. You could say no to anything.

A.L.: And I did. When they asked me, I said, “Oh, you’ve got to be kidding. No way can I dare sing that!” I’d grown up listening to Ethel Merman records.

S.S.:I never thought about the possibility of your being intimidated by the memory of Merman.

A.L.: Of course I was! But Arthur, again directing, said, “We know you can sing it; we want you to act it.”

S.S.: Ethel had one great strength: She knew how to play low comedy because it was in her bones. She knew how to do double takes. But Angie was brought up as an actress, so she had an entirely different take on Rose. Ethel was not one for analysis of character.

A.L.: I did a lot of research. But for the purposes of the show, which revealed only some aspects of Rose, I had to go with what the libretto said. Consequently, what I came up with was maybe a little bit obvious.

S.S.: No, I think you came up with Arthur’s Rose, which has nothing to do with the real Rose Hovick.

A.L.: Well, if you start messing it up with the real Rose, you’re in trouble.

Yes, it’s hard to imagine a lesbian scene in Gypsy.

S.S.:Not to mention that Rose was delicate. Even Bernadette Peters was a little more robust than the real Rose. The only person who played Rose who really looked like her was Linda Lavin.

A.L.: If I had been a little skinny woman, I would love to have tried to approach it from that point of view.

“I never thought about the possibility of your being intimidated by the memory of Ethel Merman,” says Sondheim.

But what you brought to Rose had its own authenticity.

S.S.:Early on, I said to Arthur, “What you’re writing is so strong, I don’t know why it needs songs at all.” He said, “Oh, no, if I were writing this as a play, she’d be much more complex. When I write a musical it’s in broad strokes.” And he’s right. As musicals go, Rose is a very complex character; as plays go, well, she’s a musical-comedy character.

When you next worked together, on Sweeney Todd, the character was something of both. And in a way, the tables had turned.

S.S.:This time, I had to audition for her.

A.L.: I was in Ireland when a woman called to say, “There’s a telegram here from New York from a fella named Harold Prince.” Hal said he wanted me to play the role of Nellie Lovett. I put down the phone and said to my husband, “Hmmm, all right, this show is called Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Then who is Nellie Lovett?”

S.S.:So I wrote half of her opening number, “The Worst Pies in London,” to show her. And because I wanted her to know that there was going to be some music-hall stuff, I wrote “By the Sea.”

A.L.: I understood Nellie immediately from those songs. This total London Cockney from the streets. I knew women like that—women who worked for us. Not women who were making pies out of people, but women with that wonderful jolliness and “don’t worry, I’ll fix it” attitude. That was riveting to me.

S.S.:I told her what’s fun about the characters is that the one who’s sympathetic is the morose, sullen murderer, while the one who’s good company is the real villain.

Miss Lansbury, you’ve been a good advocate for your characters.

S.S.:I remember that when we were picking the advertising for the show, somebody came up with the lovely idea of using that drawing of the guy with the knife, but it was just the guy. And Angie said, “You know, it’s called Sweeney Todd, but there is also Nellie Lovett.” And so we put in the female character with the rolling pin.

A.L.: If I may say so, I actually suggested the images in the first place. They were from a card game in Britain called Happy Families. I believe they were the butcher and his wife.

Speaking of happy families, do you two recall ever having an argument?

S.S.:No, but I don’t remember having arguments with any actor. I mean, I remember Zero Mostel having an argument with me, but I didn’t have an argument with him.

And is it true, Miss Lansbury, that you threw little pieces of dough at the conductor in the pit, as has been reported?

S.S.:Angela does not break the fourth wall.

A.L.: I’m too busy staying behind the curtain in terror. Though, may I say that I think I introduced a lot of humor into the playing of Sweeney Todd. Which was unexpected and necessary. That was the Cockney way, you know. Her logic and ingenuousness were what made her funny, and this is what allowed one to be totally serious about the most dreadful idea.

S.S.:When an actor says, “I created the character,” I used to think, “No, you didn’t; the authors did.” But I came to understand what it means from their point of view. Angie would question a line or an emotion or an attitude and say, “This seems inconsistent.” And if I agreed with her I changed it. I mean, that’s what you do with actors, right? Sixty percent of the best plays in history have been written by actors. There’s a reason for that.

For the current revival of A Little Night Music, neither of you is creating a role in that sense. Still, the part of Madame Armfeldt, first played by Hermione Gingold, seems to have been written for someone like Angela Lansbury.

A.L.: Interestingly, Hal Prince originally approached me about playing her daughter, Desirée. I couldn’t because I was doing Gypsy. But Armfeldt has always been out there in the ether; it was a natural for me.

S.S.:After the run of Sweeney Todd Angie was really exhausted, what with the constant running around the stage and up the stairs. She said, “What I want now is a nice play where I sit behind a desk.” Last night, watching Night Music, in which she’s in a wheelchair behind a tray table all evening, I thought: Good for her—she finally got one.

A.L.: I like and understand Madame Armfeldt’s indomitability, that she was a courtesan of her time, and that she maintained this style because it brought her monetary success, jewelry, recognition, a place in society. She didn’t come from any particularly great family, she just was terribly good at what she did. To see that tremendous imperiousness crumble makes the part of enormous interest to play.

And this time you weren’t worried about dying onstage?

A.L.: I did say to Trevor, “Am I really going to die?” Because I thought, “Maybe she could just drop off …”

S.S.:The original stage direction for her dying said that her wig slips slightly off her head. After Gingold read and sang for us, she said, “I notice certain characteristics that I share with Madame Armfeldt. In the script she’s 74 years old. Well, I’m 74.” And she said, “I also notice that in the last scene Madame Armfeldt dies and the wig slides off her head. Well, gentlemen”—and she took her hair off and revealed an entirely bald head. She said, “Thank you so much for seeing me,” and left. And you heard three jaws hit the floor. Hal said, “She’s got the part.”

She wasn’t really bald, was she?

S.S.:I have no idea. But I’ll tell you this: She was 75.

Miss Lansbury, would you ever go that far to get a role?

A.L.: No, I’d just act.