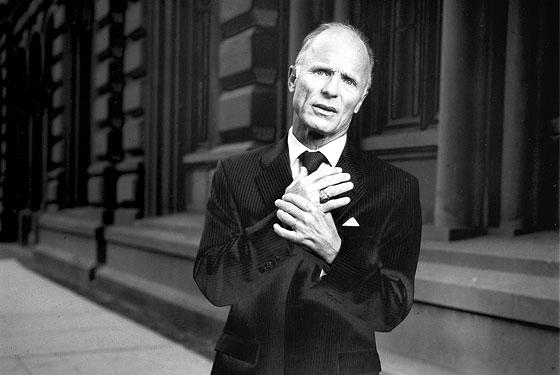

W hen Ed Harris is talking to you, even when he’s seated just inches away across a café table, he focuses on some point in the not-so-near distance. It’s slightly unnerving; more alarming, every once in a while—bang—he looks right at you, blue eyes squinting with an eerie intensity. His body tenses a bit, the lines on his forehead seem to deepen, and then, just as suddenly, the storm passes and the placid, chilly surface returns.

One of these moments comes, oddly, when he’s waving away his reputation for being so deathly serious. (It doesn’t help that he’s wearing a funeral suit.) “I have a good time, I laugh and goof around and get silly, but I don’t like bullshittin’,” he says. “So, I guess that comes across as serious.” But, he offers, “come see me in this show and ask me the same question.”

Harris’s dour getup is a costume; he’s rehearsing his part in Neil LaBute’s new one-man play, Wrecks, at the Public, which Harris swears is “pretty funny at times” and “not mean.” But if you’re waiting for him to demonstrate his silliness, give up now. It’s just not what he does. Witness some memorable moments in his long acting career: humming “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” while reentering the atmosphere as John Glenn in The Right Stuff; menacing Maria Bello with his glass eye in A History of Violence; hurling paint in Pollock (and throwing stuff off-camera as well). Willfully or not, Harris, 55, has cultivated a masculine mystique in the mold of Paul Newman and Clint Eastwood. In theater, his closest compatriot is Sam Shepard, who cast him as an unhinged cowboy in 1983’s Fool for Love. He’s a lesser god in the pantheon of mythic American men.

But a Neil LaBute character? The naughty Mormon’s anti-heroes are alpha males, too, but they’re slimy and duplicitous. They love bullshitting. Wrecks isn’t a typical LaBute play, as LaBute will tell you: “There’s none of the kind of cruelty that some of the male characters have perpetrated in other pieces,” the playwright says. At his wife’s funeral, a man named Ed gives a 75-minute monologue about his wonderful but complicated marriage. LaBute calls it “a love story.”

There is, nonetheless, the requisite dark secret, and a morally ambiguous twist. If I were to reveal it, there’d be trouble. “I’ll come and get you,” Harris promises. Suffice it to say that beneath his devoted exterior, the hero of Wrecks is a man who has flouted all order and convention in a desperate bid for control over his life. He’s another kind of outlaw. LaBute praises Harris’s “coiled performance” as a man with “a fury in him.” As Harris puts it, “He has a certain code of ethics. He’s out there, though—he doesn’t give a fuck. He’s, you know, his own animal.”

In his other October project, the movie Copying Beethoven, Harris’s intensity is more blatantly unleashed. No stranger to fiercely creative characters, he says the ailing, deaf, and defiantly productive genius was his most difficult role to date. “I’m not a piano player,” says Harris, who took lessons to prepare. “I’m not from Germany. I didn’t live in 1827. I’m an actor from New Jersey, born in 1950, so for me, it seemed like a stretch. A good one.”

T enafly is just a few miles from Manhattan, but when Harris crossed the Hudson to attend Columbia, it wasn’t to bask in the cultural riches of seventies New York. “A pure jock” in high school, he’d been recruited to play football. Yes, he dropped out after two years to pursue acting, but it wasn’t Broadway or the Village scene that enticed him; it was the college productions he saw while visiting his parents, who’d moved west to Oklahoma.

“It’s ironic, it’s ridiculous,” he says of learning to act in Norman, Oklahoma. But Columbia had no theater department at the time, and “I wasn’t worldly enough to go to the Actors Studio.”

He finally got his degree at Cal Arts, and made his home in Malibu, which you’d think was as wholesome as Iowa with an ocean view, to hear him describe his long marriage to Amy Madigan and the double-brick clubhouse he built for his daughter. No longer a “pure jock,” he still managed to bring a certain brawn to his varied roles. It’s there in his portrayal of Beethoven as a virile, egotistical iconoclast. Railing at God and tearing off his shirt for a vigorous bath, this isn’t Gary Oldman’s Beethoven; it’s more like Harvey Keitel with better abs and diction.

It’s no accident that Harris found a fellow traveler, and the project of his life, in Jackson Pollock—the brutish American artist who broke sophisticated Europe’s monopoly on painting. Harris built a small studio in which to mimic Pollock’s techniques, those seemingly wild, random patterns that were actually tightly controlled. It took ten years to get the biopic made, and when he couldn’t find a director he liked, he took the job himself. In his behind-the-camera debut, he too learned how to lose control to get control. Once, he hurled a chair in order to elicit a stronger performance from Marcia Gay Harden. She ended up thanking him.

A small, savvy fan base has fallen for Harris’s melding of the arty and the manly: He’s often called the “thinking woman’s sex symbol.” But the larger audience, those who can’t quite match the name with the gaunt face, see just another indelible but anonymous villain-or-sidekick character actor.

Maybe that’s why Harris bristles when discussing his public image; here comes that cold, blue stare again. “I don’t know what my persona is. I don’t give a fuck either, to tell you the truth.

Once, he hurled a chair in order to elicit a stronger performance from Marcia Gay Harden.

“Perhaps that’s a drawback to my career,” he adds, “because I haven’t tried to get into a place where I’m playing the same guy over and over again. But to me, what’s fun about it is being as neutral as I can—not in life, but when I work.”

Pollock was in many ways the ultimate Ed Harris movie, a triumph for actor and director, but he still took a personal loss on it, and “I had to do some work afterward”—Enemy at the Gates?—“that I probably wouldn’t have done otherwise.”

But then came The Hours and, with it, his fourth Oscar nomination. Now he promises to do more New York theater when his daughter leaves the house, and to “direct a few times before I leave the planet”—beginning with a Western called Appaloosa, starring Viggo Mortensen and Diane Lane. Will more chairs be hurled?

“I think what you’re trying to get at is I’m some kind of control freak, which I’m not,” he says later. “Over the years, you learn to give that up, you realize you only have so much control.” He’s open to different things. He’d like to be in a good comic role, for example (and Wrecks, despite his protestations, is not that). But the only one he’s done so far was Milk Money, a 1994 dud about a few dudes who hire a stripper. It isn’t one of his favorites. Then again, “I had some woman tell me it was her favorite movie the other day, so what are you gonna do?” He offers a shrug and—finally—a long, crooked smile.