The stars of Mauritius are two tiny slips of paper that have the power of Frodo’s ring and the Maltese Falcon’s catnip effect on top-shelf character actors. A pair of half-sisters, mourning their recently deceased mother, must decide what to do with the spectacularly precious stamp collection that’s been left to them. There to help are three panting philatelists willing to bully, connive, cheat, and, if all else fails, conduct a legitimate business transaction to gain control.

It’s always been possible, if unlikely, that some playwright would do for obscure postal treasures what Susan Orlean did for rare orchids. Now that New York has a stamp play that really does hold your interest—it coughs up some laughs, too—the big surprise is that Theresa Rebeck has been the one to write it. Well-observed but not incisive, clever without being especially funny, her recent plays haven’t been very good, but they’re full of the kind of ideas that somebody good ought to tackle: a showbiz satire (The Scene), an update of Greek tragedy (The Water’s Edge), a dinner party in hell where all the talk is about current affairs (the co-written Omnium Gatherum).

At the Biltmore, Rebeck yet again has the right idea, only now her reach doesn’t exceed her grasp. The story clicks along with crisp professionalism, seeming to be guided less by authorial fiat than by the eccentric desires of the people it portrays. You’d take these little pleasures for granted in any halfway-competent movie, but on Broadway, things being what they are, it counts as a minor revelation to reach the one-hour mark of a new play and realize you aren’t growing bored.

Rebeck keeps you tuned in by embracing the conventions (which are really the restrictions) of a genre—specifically, the caper story. Her play gets its focus and narrative drive from striking little chips off the Mamet block. Fans of the master may notice flashes of the hustle of Glengarry Glen Ross and the backstabbing switcheroo of American Buffalo. Now and then, there’s some wearisome family drama between angry young Jackie (a nicely poised Alison Pill) and distant Mary (Katie Finneran) about what to do with the stamps, which mean different things to the sisters because of their different relationships with the family. But Rebeck wisely leans on plot, plot, plot: five canny people trying to think up ways to outmaneuver everybody else.

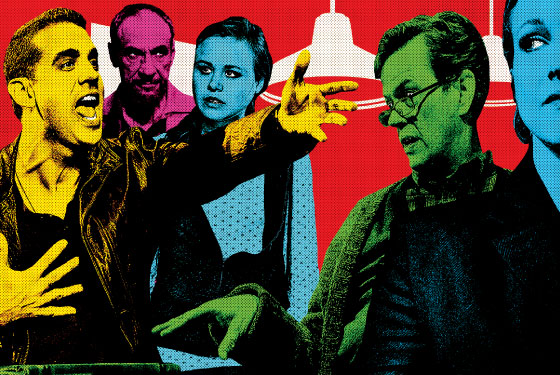

The overlapping scams may not yield much that sticks with you after the curtain drops, but they’re plenty entertaining. For this, give thanks to Doug Hughes. As in Doubt and countless other shows that he’s finessed into shape lately, the director helps his actors find every vile and redeeming nuance of the flawed people they depict, with sharp, surprising results. Dylan Baker plays the condescending expert who really is as smart as he thinks he is (damn him), and F. Murray Abraham is the thuggish collector whose lust for rare stamps propels him both to flights of profanity (“The Royal Philatelic Society had a fucking show, fuck them, the self-righteous bastards, putting a fucking piece of glass in front of those stamps”) and to the raptures of a sculptor before the Pietà. But the production’s real delight is Bobby Cannavale. Though he looks like the show’s heavy, in fact he’s a sweetheart, all leather-jacketed, outer-borough charm. In an interview recently, he said Rebeck wrote this role for him. Now, that’s clever.

Sin has a palpable, almost Catholic weight in The Power of Darkness, the rediscovered play by Leo Tolstoy now at the Mint. Nikita, a philandering, atheistic farmhand, blithely sleeps with the lady of the house, but only after ruining another girl and racking up countless misdeeds. When the master dies—a departure coaxed along by Nikita’s diabolically amoral mother (played by a chilling Randy Danson)—the consequences are profoundly upsetting, for characters and audience alike.

Martin Platt’s production of his colloquial new English version can be slow at some points, shrill and shouty at others (it’s probably easier watched from row F than from row B), but artistic director Jonathan Bank deserves credit for finding yet another dusty gem. Here’s a story that crams the betrayal, greed, and—in a genuinely nauseating scene—the murdered child of Macbeth into one little Russian town. The Mint gets livelier by the year, not least by finding fresh ways to remind us that there were a lot of bad, bad people in the good old days.

BACKSTORY

Philately has had scant stage presence, but it pops up intermittently in the movies—and not always as the creepy pastime that made Woody Allen suspicious of his neighbor in Manhattan Murder Mystery. Rare stamps were the MacGuffin in the last short film of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalogue series about the Ten Commandments. The 1988 Canadian film Tommy Tricker and the Stamp Traveller made collecting a minor fad up north (the filmmaker strived to “sensitize kids to other cultures through stamps”). More recently, Fabián Bielinsky’s Nine Queens, an Argentine counterfeit-stamp caper, won a pile of awards on the festival circuit but had only limited release in the U.S.

Mauritius

By Theresa Rebeck. Biltmore Theatre. Through November 25.

The Power of Darkness

By Leo Tolstoy. Mint Theatre. Through October 28.

E-mail: theatercritic@newyorkmag.com.