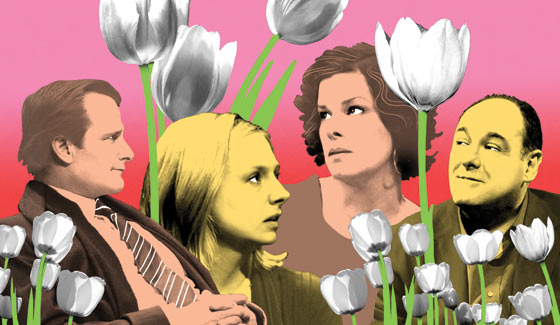

One fifth-grader strikes another on the playground, breaking his front teeth. The children’s parents, matching sets of archetypally awful upper-middle-class professionals, convene to broker a peace deal—no lawyers, no accusations, just enlightened beings in search of a lasting accord. It’s all very civilized—but, this being a play by Yasmina Reza (Art), the Don King of bourgie angst, a veneer of civility is merely an invitation to a prizefight. And soon enough, the haymakers are flying: “What I am and always have been is a fucking Neanderthal!” declares Michael Novak (James Gandolfini), the victim’s reluctantly domesticated dad. “Women who are custodians of the world depress us,” decrees lawyer and demon-male spokesperson Alan Raleigh (Jeff Daniels), whose son did the smiting. And then there’s his wife, Annette (Hope Davis), an ice sheet over a vast reservoir of boiling bile, who delivers this uppercut: “Our son did well to clout yours, and I wipe my ass with your Bill of Rights!” (Even at their rhetorical heights in the dock, Saddam and Slobo never had zingers that zingy.) The addressee in each of these cases is Veronica Novak (Marcia Gay Harden), mother of the aggrieved and a tireless (if tone-deaf) apostle of universal justice. She belatedly concludes, “Courtesy is a waste of time, it weakens you and undermines you.” Pow! Biff! The hits just keep coming. So why does God of Carnage, for all its witty anarchy and farcical cheek, feel a little flabby in the gut, a little punch-drunk and glass-jawed—and, even at 85 minutes, a little padded?

Maybe because it’s all too easy. This fight feels fixed: the punches telegraphed, the reversals rehearsed. The cozy bassinet of gentrified Brooklyn (where child-rearing is art form, fashion statement, and blood sport, all in one) is about as big a bull’s-eye as the boulevard affords. (Reza’s longtime translator, Christopher Hampton, has repatriated the story from a tony Paris arrondissement to Cobble Hill.) Even the casting feels too perfect, as if calculated by some Netflix algorithm. Each of this fearsome foursome fills precisely, yet never exceeds, his or her assigned quadrant: Who gives smug-lout better than Daniels—more than once, he nearly steals the show—and who but Davis could hold her own as his aggressively phony spouse? (Her much-buzzed-about projective vomit scene lives up to the hype—take that, Albee, with your prim, offstage Virginia Woolf emesis!) Harden, the martinet, is our attack schnauzer. And then there’s Gandolfini, cast as a capo in the Brooklyn stroller mafia: Nobody looms better, looms harder than the former Tony Soprano. A cloud of implied violence follows him everywhere. (Recalling his youth, Michael says mistily, “I had my own gang,” and the crowd goes wild.) But as Michael grows more openly Sopranos-esque, he’s also less interesting. He simply erupts, and the damage feels minor, compared to the dire predictions.

That’s God of Carnage in a nutshell: 30 thrilling minutes of hurricane warnings, followed by a nasty cloudburst that just won’t end. You can feel the play trying mightily to shut itself down—characters head for the door, only to dive back into the fray for more, as if Reza herself were just offstage with a cattle prod. But war—what is it good for? What’s the meaning of all this highly symbolic, spryly shambolic roughhousing, which never quite rises to the level of “carnage,” or even vintage Jerry Springer? Despite repeated references to Darfur and the ICC, Reza doesn’t really have the stomach for a blood-feast: Try as she might, she lacks Mamet’s misanthropy. Her most comfortable modes here are dyspepsia and elegy—she’s as disappointed with these characters, with their half-assed savagery, as we are—and these moments are where the play is at its best. (Veronica’s final reverie on the death of a hamster is a sad and lovely psalm to that smaller, stranger God, the God of Absurdity.) Reza toys with something primal and sanguinary, but what she’s prepared to deliver is a puggle-on-puggle dogfight, played out in the safe precincts of Prospect Park. The results are curious, pathetic, often amusing, but nothing, really, is at stake. Place your bets. –S.B.

The first two-thirds of Michael Jacobs’s Impressionism are so indistinct and unfocused they make Monet’s water lilies look like photo-realism: Joan Allen plays Katharine, a Manhattan art-gallery owner who can’t part with her high-end merchandise, which symbolizes bits of her past she’s not yet ready to shed. Katharine’s employee, Thomas (Jeremy Irons), a photographer who used to shoot in Africa for National Geographic, is as even-tempered as she is high-strung. He’s also a coffee aficionado, and he shares his wisdom with Katharine; she reciprocates by singing the praises of a cranberry muffin by a local baker (played, marvelously, by André De Shields). They banter and brood cleverly and self-consciously, and in between, dramatized flashbacks show us the lives they led before they were trapped in a sleepy gallery. Customers—including one played by Marsha Mason—alleviate the tedium, but just barely.

And then, in the last half-hour of Impressionism’s single act, Katharine and Thomas’s world opens up like one of those Monet lilies. The play’s director, Jack O’Brien, has shaped it so that we can’t be sure what’s going on until the very end, when we step back from Katharine and Thomas’s daubed-on dots and dashes of conversation and see the broader pattern of their relationship to each other.

The material’s surprise revelation is more a handy way out of the characters’ incessant talkiness than a satisfying, believable conclusion, but at least it gives us something to hang on to. Allen works hard to make Katharine sympathetic; we can see that she’s wounded, not just self-centered and abrasive. But the performance is too finely calibrated: It clacks along efficiently but never breathes. As Thomas, Irons has the luxury of being relaxed and charming, even though his character, too, harbors painful secrets. Irons’s performance is comfortably rumpled and lived-in, an effect that requires meticulousness and discipline. His gift is that he makes hard work look like a shrug. –S.Z.

God of Carnage

By Yasmina Reza.

Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre.

Impressionism

By Michael Jacobs.

Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre.