After a few years of silence, sitcoms are giggling again. ABC has had modest success defrosting Tim Allen for Last Man Standing, a multicamera show—the traditional kind, with a flat living-room set and an audience in the studio. CBS, which never abandoned the form, launched a top-ten hit with 2 Broke Girls. NBC, whose critical darlings like 30 Rock and Parks and Recreation have been shot “single-camera,” sans audience, has gone back to the old multicamera setup for Whitney. And on every one, the audio track is filled with raucous laughter. At the upfronts last spring, when Whitney made its debut, critics and reporters noticed that the guffaws came in hard and abruptly, then evaporated. Is it possible that actual human beings respond to a barrage of vagina jokes with such gusto? And if so, why is it that a 59-year-old Hollywood sound engineer named John Bickelhaupt is so busy this fall?

Bickelhaupt, whose formal title is “re-recording mixer,” is one of just four or five craftsmen hired by showrunners to perfect the sounds of laughter. He spends his days traveling from mixing stage to mixing stage, carrying a custom-built computer that can quickly adjust the tone, volume, and even gender of an audience. If need be, he can transform complete silence into a 21-minute symphony of mirth. Bickelhaupt has three Emmys, but he mostly avoids the spotlight. “We like to remain kind of mysterious—the man-behind-the-curtain thing,” Bickelhaupt says. “We don’t really like to talk about it too much.” (Nor do producers: Whitney showrunner Betsy Thomas declined to be interviewed for this story, as did 2 Broke Girls’s Michael Patrick King.)

Most producers claim to add no laughter to their shows. Chuck Lorre, the man behind Two and a Half Men, Mike and Molly, and The Big Bang Theory, is unequivocal: “I do not, and have never, sweetened my shows with fake laughs. I’ve always thought it was a pretty hateful and self-defeating practice.” Steve Levitan, who created Just Shoot Me! and co-created Modern Family, never went beyond fixing small technical glitches: “When used properly, the laugh guy’s job is to smooth out the soundtrack—nothing more.” Phil Rosenthal, who says he “rarely manipulated the laughs” on Everybody Loves Raymond, admits that he’s seen it done. “I worked on shows in the past where the ‘sweetener’ was ladled on with a heavy hand, mainly because there were hardly any laughs from the living,” he recalls. “The executive producers would say, ‘Don’t worry—you know who will love that joke? Mr. Sweetman.’ ” Bickelhaupt backs this up: “Yes, there are times where I’m doing all of the audience responses,” he says. “I’m not going to tell you what those shows are.”

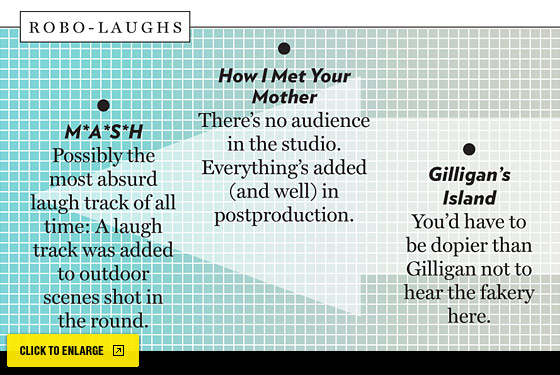

It’s often hard to tell which ones he’s hinting about, because laugh tracks can be more graceful than they once were. Take a listen to an episode of How I Met Your Mother, which is shot mostly multicamera, but in an empty studio. The laughs, digitally massaged by Bickelhaupt for broadcast, are mellow, hoots and catcalls virtually absent. He explains that producers are increasingly “shying away from that big, full audience—the raucous sound that was more commonplace in the seventies, eighties, and nineties. They want a more subtle track.” He won’t guess about whether Whitney fakes it, but another veteran sound engineer listened to a few minutes and delivered a harsh verdict: “It all sounds laid-in after the fact.”

As Whitney reminds viewers at the start of each episode, an audience is present at the taping. If the reactions sound exaggerated, producers insist that’s just because the folks who showed up found the jokes really, really funny. And Bickelhaupt confirms the notion—at least in the case of Lorre’s shows. “I’m sure that 99 to 100 percent of what you hear is his audience,” he says. Though Bickelhaupt doesn’t work on Lorre’s comedies, “I’ve worked on shows like his before.” Married … With Children, he says, “was amazing. I worked on that show for years and years, and honestly, I had little to do except clean up edits.” That owed a lot to careful casting of the crowd: Married, he says, often had audiences packed with Marines and servicepeople who responded to the show’s aggressive, anti-p.c. humor. When Bickelhaupt worked on the Judd Hirsch sitcom Dear John, about a sad sack recovering from a breakup, he says producers booked audiences from singles groups; Sherman Hemsley’s church comedy Amen brought in gospel-choir members.

Bickelhaupt’s craft has its roots in the early days of TV, when a sound engineer named Charley Douglass realized a technical need to re-create laughter. When I Love Lucy and other series were filmed, the responses were inconsistent, particularly if, say, scenes had to be shot repeatedly, with audiences laughing less heartily on each take, or when an edit snapped off the laughs in midstream. Douglass’s solution was called the “laff box,” a device that allowed him to substitute giggles and guffaws, along with applause, in place of the show’s original audio track. That early machine still exists, and it looks like a giant whirring, clicking adding machine. Each key is linked to a little individual loop of magnetic tape containing its own chuckle. “He didn’t want to let any of the technology out,” Bickelhaupt explains. “So whenever he wanted to change tracks or something, he’d go behind a curtain or in a closet.” Bickelhaupt isn’t quite so secretive, but even today’s digital machines, he says, “are pretty anonymous, with [unlabeled] knobs and buttons.”

While Douglass intended his device to solve tech problems, the networks soon got hooked on the notion of cheap, easy-to-produce laughs. In sitcoms of the sixties and seventies—Gilligan’s Island, Get Smart, The Brady Bunch, M*A*S*H (that last one over the objections of producer Larry Gelbart)—they were added, liberally and crudely, in postproduction. That’s when the laugh track earned its bad reputation. Because the tape loops were used for decades, “the joke is that all the people laughing are dead,” Bickelhaupt says. “It was true to a degree.” Bickelhaupt’s modern laff box still includes a clip of Lucille Ball’s mother exclaiming “uh-oh” during an I Love Lucy episode. It is thus possible that DeeDee Ball, born in 1892, will someday set up a Whitney Cummings vagina joke in HD. (Though probably not. “I never use it anymore,” Bickelhaupt says. “It’s in mono.”)

Sometimes, though, even the living can sound fake. Sitcoms are taped with boom microphones over both actors’ and audiences’ heads, and when a show’s audio is being mixed, producers and sound engineers artfully blend what’s being said onstage with what’s going on in the audience. “Everything sits in a natural space when it’s done properly,” says that anonymous sound guy. “But if there’s a conscious decision to reduce the sound of the audience during dialogue and boost it only when the audience laughs, it’s going to sound artificial.” Bickelhaupt confirms this, saying that the perception “all depends on how it’s mixed.” The tech further notes that tweaking audio this way allows producers to claim all-natural laughs: The audience isn’t being piped in, strictly speaking, but the real one is being amplified so heavily that it sounds odd.

All this does bring up another question: Does laugh-tracking make people laugh more? You can’t tell from the ratings. This season, the single-cam Modern Family and the multicam Two and a Half Men have been trading places as the No. 1 and 2 comedies on TV. Fox’s single-cam New Girl is arguably the fall’s breakout hit, but the multicam 2 Broke Girls has been nearly as good at luring viewers under 50, and Whitney started strongly enough that NBC ordered a full season.

Even the scientists are divided. A 1974 study published in The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology suggested that laugh tracks did prompt some laughter at unfunny jokes. More recently, however, Dartmouth professor Bill Kelley studied brain scans of folks watching samples of both Seinfeld (laugh-tracked) and The Simpsons (non-laugh-tracked), and discovered that the laugh regions of their brains lit up equally, whether cued or not. Put those two pieces of research together, and you may have your answer: If the show’s funny, a laugh track doesn’t make any difference. If it’s not, the laff box may help. Which suggests that Bickelhaupt will have plenty of work for years to come.

The Fake-Laugh Spectrum

From funny-strange to funny-ha-ha.