With a menacing shake of her curly locks, a physique as pointed and painted as a playing card, and wearing what looks like a chador or a tarpaulin, Helen Mirren’s Elizabeth I can give a sixteenth-century courtier the creeps: “Bring me news I did not want to hear … men have been hanged for less.” And we believe them both, Mirren and Elizabeth. Certainly the original Gloriana must have had something of Mirren’s Royal Shakespearean flair. Mirren also displays the same voracity for sex and ideas and the arbitrary opinionizing on everything from God to money she brought to her impersonation of Ayn Rand on cable television, not to mention the sacrifice of a personal life for professional advancement, the protofeminist sense of mission, and the passionate sonar intelligence that she brought to her portrayal of Jane Tennison in the Prime Suspect series. So it isn’t hard to imagine Mirren’s impressing such capable men inside the castle walls as Francis Bacon and Sir Walter Raleigh, and such rough geniuses on the mean city streets as Marlowe and Shakespeare. And Mirren also brings a welcome sense of humor—a gift for throwaway sarcasm, even on such fraught occasions as when she learns that the pope has issued the Vatican equivalent of a fatwa for her Protestant heresies.

We zoom in on her in 1579, more than twenty years into her reign, so she doesn’t have to be young. She seems to genuinely enjoy glad-handing motley crowds, jollying forelock-tuggers, trading elbows and a wink. Moreover, when called upon for the big scene—dismissing Essex (“We forbid you access to our presence”); delivering the Golden Speech of 1601 (“Though God hath raised me high, yet this I count the glory of my crown: that I have reigned with your loves”)—she delivers big-time, in iambs. Congratulations should also go to Nigel Williams, whose screenplay for Elizabeth I is as sassy as Tom Stoppard’s was for Shakespeare in Love. At the end of the 1500s, the English language was up for grabs; the only way to get there is to jump into the deep end.

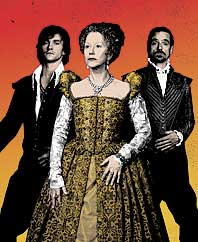

Meanwhile, we must put up with Claus von Bülow—excuse me, Jeremy Irons—as the Earl of Leicester, who played both ends to the advantage of his middle way past his expiration date. I am not as much of an admirer of Irons as Jeremy himself obviously is, much preferring Patrick Malahide and Ian McDiarmid as Sir Francis Walsingham and Lord Burghley, a pair of ministerial worms whose insinuations of advice are shrewd if heartless; Barbara Flynn as a chubby Mary Queen of Scots, as if fattened for decapitating; and Hugh Dancy as the earl of Essex, a corrupt and curly-haired imp indeed, whom the queen should have seen through straightaway but for her hormonal flush. For this two-part series, enough money was available for HBO to lease most of Vilnius, Lithuania. The producers also indulge themselves with a surfeit of castles, horses, hats, tents, and remarkably explicit disembowelings and beheadings. The only boat they miss is the Spanish Armada.

One thinks, though, of Elizabeths past. Bette Davis, whether playing to Errol Flynn in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939) or to Richard Todd in The Virgin Queen (1955), now looks overwrought. Judi Dench, however agreeable, merely slummed in Shakespeare in Love (1998). Cate Blanchett was no less arresting in Elizabeth (1998) than she is in everything else, but she brought with her that strange Blanchett aura that always makes us wonder more about Cate than the character she plays. But Glenda Jackson’s performance in a half-dozen episodes of the Masterpiece Theatre production of Elizabeth R in 1972 remains not only the pure-gold standard by which all other virgin queens will be measured—an embodiment and an exorcism—but also one of the greatest theatrical experiences available to us on DVD command. By metempsychosis, Jackson returned to the sixteenth century and set up fearful shop: Doublet, codpiece, ruff, hose! Theaters and scaffolds! Sectarian terror and bubonic plague! State torture, Jesuit conspiracies, and severed heads! Beneath her ghostly/ghastly pancake makeup, inside her mummified brocade, competing ideas of desire and duty, of woman and sovereign, circled and snarled, as if the court were a cage. Sly, furious, besieged, distraught, she somehow contained her contradictions. We believed her to be at once a great monarch (“glory without conquest … unlimited power without odium,” wrote Lord John Russell) and a creature as shadowed and forlorn as she described herself in the poem she wrote when the duke of Alençon and Anjou left her in 1583: “I am, and am not—freeze, and yet I burn / Since from myself my other self I turn.”

Elizabeth I: Parts One and Two

HBO. Saturday, April 22

and Monday,

April 24. 8 p.m.