There’s a scene in David Lodge’s novel Changing Places in which scholars play a game called Humiliation. One by one, each reveals a book he’s never read. Then a particularly competitive fellow plays a trump card: He claims he’s never read Hamlet. Poof, there goes his tenure.

In the game of TV-critic Humiliation, my personal Hamlet is AMC’s Breaking Bad, that four-year contender in the best-show-ever sweepstakes. While no critic can catch every episode of every series—unlike movies, one season of these suckers comprises twenty hours—Vince Gilligan’s masterpiece was a major oversight. And given the show’s reputation, there could be no half-measures: I had to go on a binge, scarfing up all 33 episodes on DVD. Possibly in a row. Possibly on meth.

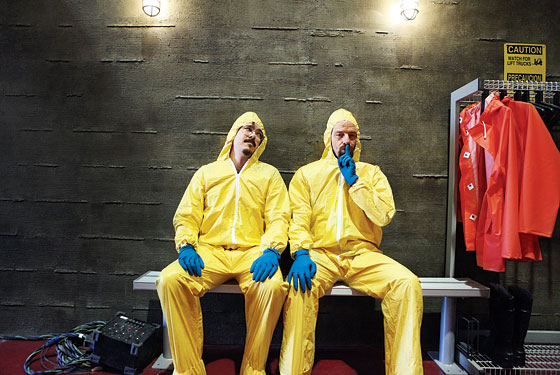

So two weeks ago, having received screeners for the long-awaited fourth season, which began two Sundays ago, that’s just what I did. Amazingly, given my Internet habits, I was unspoiled: I knew Breaking Bad was about a high-school teacher played by Bryan Cranston who gets cancer and starts dealing meth. I knew it was set in Albuquerque. I was aware that the show had lush production values and featured an anti-hero, moral ambiguity, and themes related to the economic collapse, but these days, that could describe half the cable schedule.

In any case, all those years of holding my fingers in my ears and saying la la la paid off, because my week of Breaking Bad ended up being one of the best experiences of my life—and if that sounds crazy, maybe you just don’t love TV enough. At first, I was tugged in by the sheer physical grandeur of the cinematography, still a rare quality for TV. Then there was the dark wit and that cast of characters who were somehow both realistic and cartoonish, symbolic and unpredictable, giving it the aura of a fable. But to my surprise, the show was also just plain pleasurable, not a chore the way I had imagined it might be, and so I sank in to enjoy daylong marathons, happily jumping cliffhangers, ignoring the world and my family in favor of Cranston’s Walter White and the loved ones he was betraying and deceiving.

Two seasons in, I began to feel almost dizzy with the fact that after years of identifying as both a fan and a critic—two roles that, by definition, require fellow travelers—I was for once watching truly alone. I wasn’t worried the show would be canceled. I had sailed past waves of buzz, raves, and backlash, past interviews with Gilligan and Cranston, misleading promo reels, casting news, and Twitter debates. I was in deep, clear waters, free to enjoy the ride. Bliss.

Stepping outside the audience this way made it easier to enjoy the show’s story as a whole. But I also felt freer to detach myself from viewing it in episodes at all, taking the narrative in instead as an imagistic poem, one in which that first-season vision of the “raspberry slush” corpse paralleled the crushed meth lab of Season 3, and the drifting teddy-bear eye came back as the surveillance camera installed in the fourth season’s premiere episode.

On the surface, Breaking Bad is about drugs, like Weeds, and about organized crime, like Boardwalk Empire. But the deeper I got, the more the series began to feel more universal, less a story about thugs than one about intellectual arrogance. Walter White is as much an amoral artist as he is a wannabe gangster, his pride in being the perfect meth cook more of a turn-on than the money or the violence. Even unfinished, the show felt like the crucial linking ring in a decade of cable meditations on masculine pathology, with Walter standing shoulder to shoulder with Tony Soprano, Don Draper, Dexter Morgan (and if you stretch a bit, “Lights” Leary, the hooker on Hung, Hank Moody, Vic Mackey, Louis C.K., Nate Fisher, Larry David, and even those zhlubs on Men of a Certain Age).

Like many of these shows, Breaking Bad plays to the craving in every “good” man for a secret life. But unlike some of its more audience-pleasing peers, Breaking Bad has shied away from making Walter into a mere badass rule-breaker for viewers to live through, foregrounding instead his more repulsive qualities: his coldness, egotism, and self-pity. Walter is smart enough to have insight, but like Tony Soprano before him, these epiphanies never stick. In the episode “Fly,” he is a whispering penitent, calculating the precise moment he should have died. A few hours later, he does face death, only to make the most selfish choice possible, taking moral hostages in the process.

When I was done, I hit eject. I went and got more popcorn. And then, of course, came the fall. I read some magnificent old end-of-season interviews with Gilligan on Alan Sepinwall’s blog, then a few recaps on The Onion’s A.V. Club, then Chuck Klosterman’s pre-season-four Grantland piece on the show, arguing with him in my head. (Really, Klosterman? You’re rooting for Walter instead of wishing him dead?) I read The New York Times Magazine’s profile of Gilligan. I listened to the commentaries, getting great tidbits (like the fact that “Saul Goodman” is a homophone for “S’all good, man”), but also knowing that I was turning a fever dream back into a mere show, built by writers and directors, viewed by a mass audience, under economically specific restrictions, then released over time, contingent, communal, limited. It was particularly nerve-racking hearing Gilligan muse about how many more seasons the show would go on, a decision I knew hovered very much in the real world, based on network needs and Gilligan’s own understandable desire to keep the best job he’d ever had.

In other words, I was back to watching TV as practice, not theory. Binge-watching a show like Breaking Bad is probably the purest way to watch a great series, but if everyone watched this way, no great series would make it past the first season. As with Walter’s blue meth, it’s the price we’re willing to pay for the good stuff.

See Also:

A Guide to Catching Up on Breaking Bad

Breaking Bad

AMC.

Sundays, 10 p.m.